THE seizure of Fort Rupel I have related in a chapter on our relations with the Greeks.

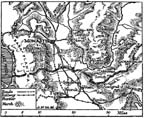

It effectively blocked one of our most feasible lines of advance. Admittedly the fact that we had no railway up to the Struma, but only the hilly Seres road, would have made a march on Nevrokop or Petritch a difficult operation from the point of view of supply. The use of a railway to the mouth of the Rupel pass might indeed have been secured, as a glance at the map will show, by driving the Bulgars off their hill-positions behind Doiran town so as to get the use of the Junction-Salonica-Constantinople line which there makes a right-angled turn to the east. The attempt to free this corner by Lake Doiran of the enemy was begun in the late summer of 1916 by the French, abandoned when the Bulgar offensive from Monastir towards Ostrovo on our western wing developed, and renewed by ourselves in April and May, 1917, when the elaborate defences and heavy artillery which the long pause had enabled the Bulgars to establish there proved too much for us.

Their descent upon Fort Rupel,---a movement arranged with the connivance of the Greek Government, whose betrayal of their territory to their natural enemies had been purchased by a German loan,---together with its sequel of an advance upon Kavalla,---enabled the Bulgarians immensely to improve their strategical position in the Balkans, for they thus linked up their eastern and western forces between which the Greek districts of Seres and Drama had previously been a wedge. With the single inconvenience of bulk-breaking at the Demir-Hissar bridge over the Struma, which the French had blown up in January, 1916, train communication was made possible from Doiran to Okjilar, in the part of Bulgaria that comes down to the Ægean. When we moved up to our positions on the Krusha-Balkan mountains and the Struma river our guns came close enough to this railway to stop the use of it for through lateral communication, though in the thick of the fighting which resulted in the taking of Yenikeuy on the Struma in October, a Bulgarian train loaded with ammunition deliberately steamed along in full view, dumping its cargo at different places, and got safely away again, though one or two of our shells seemed to go right through it.

But the principal advantage to the Bulgars by their occupation of Greek territory between the Struma and the frontier was that it made it possible for them to bring reinforcements and supplies from Eastern Bulgaria or even from Turkey all the way by train with the greatest convenience; the railway on the east of Seres was too far away from our lines for us to interfere with this use of it.

Later on, in August, when the Bulgarian plans for a general offensive against us were mature, and simultaneously with their attack upon our left wing which led to the battle of Ostrovo, they advanced further southwards from Rupel to the Struma, pushing before them the French forces that were beyond the river. Some confused fighting took place during the whole of one day, and a column of British yeomanry was sent out, which carried on a rearguard action while the French were getting back over the Orliak bridge, the only line of retreat open to them. This retirement had been foreseen as inevitable, should these circumstances arise, owing to the weakness of our force compared to the enemy. The object of going beyond the Struma had only been to hold bridgeheads, not to occupy territory permanently.

But events on the Struma were of small importance in comparison with the Bulgarian offensive in force upon the wing of the Allied front, the brunt of which fell upon the Serbians, who had lately taken up position there and who were at first pressed back as far as Lake Ostrovo.

As I have said elsewhere, when the construction of the entrenched camp was finished General Sarrail began to move his forces up to the Greek frontier on the other side of which the Bulgars were. His twofold object in entrenching himself there was to stall off a possible enemy advance on Salonica at as great a distance as possible from the entrenched camp, and also to hold the enemy along the whole line, while gradually and as secretly as possible concentrating troops at one point to make there a sudden offensive movement of his own.

The point he had chosen for this attack was the valley of the Vardar. It was chosen because the railway ran up the course of the river, and a modern army, must have a railway behind it if it is to fight its way any distance.

To co-operate with this plan, the British Army in Macedonia thinned out its line on the Struma, (though faced with the risk of a reinforced enemy attack from the Bulgarian division concentrated at Xanthe, and other columns advancing from the north), and massed two divisions south of Doiran, while holding two others ready to move there also, if necessary, to give backing to the French in their thrust up the Vardar valley. This attack up the river would probably have been followed by a push from Monastir. But Sarrail's plan was for the Vardar operation to be carried out first, both to draw Bulgar forces to that sector and to make it appear that the arrival there by British troops was to reinforce and not replace the French.

For this Vardar attack the manifold preparations necessary were meanwhile being made. When you want to go anywhere with wheeled traffic in the Balkans you have first of all to build a road in the direction you have chosen. This General Sarrail had done. He had furthermore gathered his heavy artillery, worked out a scheme of transport, arranged the supply of food and ammunition, and made all the various dispositions required to put an army into action on a certain front.

But our schemes in the Balkans have never been more than a small part of the vast operations of war going on all round Europe, and they have consequently always been controlled and conditioned by considerations arising in connection with other theatres of war. It is the function of the Allied War Council, which alone has the means of seeing the military situation as a whole, to co-ordinate movements in all these different zones of operations, to check action although it may appear locally desirable in one place, to order an offensive in spite of its seeming doomed to failure in another,---all for reasons arising out of strategical considerations of the widest nature.

On such legitimate grounds as these, no doubt, the prepared offensive of the Allies in the Balkans was delayed by successive orders, though meanwhile the local tactical situation and the need of holding enemy forces there obliged General Sarrail to make a limited attack with French troops at Doiran which succeeded, under cover of the Anglo-French artillery, in taking Tortoise Hill and the village of Doldzeli, while the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry co-operated by taking Horseshoe Hill.

It was reasons of higher strategy and politics which led to the postponement of General Sarrail's attack. To have brought the Roumanian Government to sign a convention of alliance was a diplomatic triumph for the Allies, but there yet remained a period of ten doubtful days between the signature of that convention and its ratification by a formal declaration of war upon Austria and Bulgaria. During those ten days Roumania might still have changed her mind, and it is now no more than a matter of history how both the Central Powers and ourselves vied in bluffing against each other (it is not the exact word in our case, but none conveys the impression so exactly) during that critical period while the adhesion of our new Ally yet hung suspended in the balance.

In the Balkans the pressure which the Allies brought to bear to reassure the Roumanians took the form of ordering that the push forward up the Vardar valley should begin. If this attack met with success in the first week's fighting, the encouragement to Roumania to clinch her entry into our alliance would be considerable. The victorious advance of the French from the south would be an incentive to Roumanians to repeat, even though under more difficult conditions, their own march upon Sofia of 1913.

But Bulgaria's bluff forestalled ours. It was her object to cow the Roumanians into continuing their neutrality by putting before their eyes the spectacle of a successful Bulgarian offensive in Macedonia.

German agents---who swarmed at Bucharest, which always reminded one of a German Residenz-Stadt rather than of the capital of an independent race,---together with the Press of the Central Powers, vehemently announced that the moment had at last arrived when the Allies would be driven, not only back to Salonica, but into the sea. Owing to the delays of the Allied Governments the initiative in the Balkans had, indeed, passed to the enemy.

All the disposition of the French, then, had to be recast, and owing chiefly to the lack of bridges over the Vardar it took a fortnight to get their guns from the Vardar-Doiran front out to the support of the Serbs, who needed them so badly. The latter, taken by surprise owing to connivance in the Bulgarian advance by the Greek troops on the frontier, were driven from ridge to ridge until they had their backs to Lake Ostrovo. There they held their ground until the French were able to get into position on their left flank. When that had been accomplished a counter-offensive was started that gradually, with many delays and checks, carried the Allies back over all the ground they had lost and eventually into Monastir itself.

The line which the Bulgars had held from the time they captured Monastir in November, 1915, until this attack of theirs in August, 1916, lay along the Serbo-Greek frontier. The sector on which they now advanced was limited by the commanding height of Kaimakehalan in the east and by Lake Prespa in the west.

The Serbs were separated from the Bulgarians by a fringe of Greek frontier-guards. During the night of August. 17th those frontier-guards unobtrusively withdrew, leaving the way clear for the Bulgars to press on and attack the handful of scattered Serbs at Florina with all the advantage of surprise.

The Bulgar advance began at 2 A.M. Two columns, each of one regiment of infantry, with several guns, marched southwards across the Greek frontier one through Negocani, the other through Sakulevo and Vrbeni. The concentration and the preparations made for these columns to move had been carried out secretly, and they came by little-used hill-tracks.

The feeble Serbian outposts stationed to the north of Florina could no nothing but retire before the overwhelmingly superior strength of the Bulgars, though they offered what resistance was possible, and when, at 10.15 A.M., the Bulgars with 100 German pioneers occupied Florina station, which is three miles from the town, they had not made this progress without loss.

But the advance of the enemy had already cut off all the other Serbian irregulars. to the west of Florina and they were only able to get back to the main body of their army, after losing 120 killed and wounded, by making a great detour through the mountains southwards, travelling only by night over unknown paths.

On August 18th, in the early morning of the day following their first move across the frontier, the Bulgars attacked the Serbs with about 12,000 men. The Serbs could only gather half that number to oppose them. The fight took place along a line from Boresnica through Vostaran to the Ceganska Planina heights, and as a result of it the Danube division fell back onto Leskovec, Vrtolom, and Rosna, all of them villages south of the Monastir road.

On August 19th there was a hotly contested fight round Banitza, where the road from Monastir branches off, one arm to Salonica, the other southwards to Sorovitch. At 6 P.M. a mass attack by six battalions of Bulgarian infantry took Hill 726 beside the town, and the Serbian troops holding Hill 950 further to the south were forced back to the east of Cerovo. The retreat was made in good order, and the next Serbian line of defence ran from the northern end of Lake Petrsko along the Malkanidje range of hills to the Ceganska Planina.

The following day, August 20th, was the most critical of all. The fighting was being carried on in great heat on these stony hills where it was absolutely impossible to dig, and where the only shelter to be obtained consisted of a heaped parapet of stones which, if a shell struck it, was an added danger rather than a protection. The Serbs suffered much from lack of water. Fortunately the Vardar division which had been away back in reserve was beginning to arrive by now, but for all that the Serbian centre was forced off the Malkanidje ridge onto the hills which form the very bank of Lake Ostrovo. And now the situation became really serious. Losing ground west of Lake Ostrovo did not matter much but if the Serbs were forced to abandon this last ridge before the lake there would have been no way of retreat for them except around the northern end, and that would have left it open for the enemy to advance round the other end and cut the railway to Salonica between Agostos and Vodena, so putting themselves astride the Serbian line of supply. The 17th Regiment of the Drina division was sent to reinforce the Danube division at the threatened point, while the rest of the Drina on the Serbian right wing went further to the north, attacked and took the lower Spurs of the steep mountain Kaimakchalan.

The success of the Bulgarian offensive had reached high tide, however. Their soldiers were boasting exultantly, as we heard later from the peasants of the villages they occupied, that they would be in Salonica in a week. The rapidity with which they had crumpled up our left wing and the advantages which they enjoyed, thanks to the complicity of the Greek authorities and the native inhabitants of Bulgarian race of the region they were fighting in, doubtless encouraged confidence. Their columns were guided in their advance by Greek gendarmes in uniform, and their cavalry patrols even succeeded in getting round to the eastern side of Lake Ostrovo.

But the capture of Pateli, which reduced the Serbian hold on the western bank of Lake Ostrovo to one-half of the length of its shore, was the last success that the Bulgarian invasion registered. After that they seemed exhausted, as, indeed, they might well be, at the end of a whole week of such marching and fighting as they had had. And meanwhile the Serbs were growing daily stronger. A brigade of the Timok division, which was in general reserve down at Vodena, arrived; the irregulars, the best fighters in the Serbian Army, suddenly appeared on the left wing after their precarious retreat from Florina; the first detachment of French and Russian reinforcements were getting into line at the southern end of Lake Ostrovo.

On August 22nd five separate Bulgar assaults on the ridge west of Lake Ostrovo were beaten back by counter-attacks. The losses of the enemy were estimated at five times those of the Serbs.

This was the climax of the battle of Ostrovo, and its further development, and ensuing conversion into a successful Allied advance, is told in the chapter on the push for Monastir.,

.

WHEN the Allied Forces first left the entrenched camp and marched up towards the Greek frontier to make a new line there, French troops originally moved in all three of the principal directions,---towards Seres, Kilkish and Monastir. The result was that the British on the Seres road and in the Kilkish area found themselves interspersed with French. General Sarrail's aim in this arrangement was that he wished French troops to be available to take part in any action that might occur, and it could not be certain where fighting would begin. But General Milne, and his Chief of Staff (General Milne having succeeded to the command from General Sir Bryan Mahon in May), saw, in this mingling of Allied forces, a danger of confusion. The different supply-systems would conflict on the limited routes available, and the lines of communication of the French and British Armies, instead of being separate and distinct, would intersect each other. So, with a view to securing administrative efficiency, General Milne asked General Sarrail that the English might be accorded an independent and homogeneous sector of the Allied Balkan line; and General Sarrail agreed to this at once.

The reshuffling of divisions thus rendered necessary led to a good deal of marching and countermarching that seemed futile and aimless to the troops who had to do it, but which simplified considerably the organisation of the British force.

Before the change was made, one of our divisions had been since April 18th at Kilkish, with a French division on the left, and two French divisions carrying on the line to its right. Our division's front was from Hirsova to Dereselo, a trench-line of about 10,000 yards. We had no exact junction with the French, but they said that in case of a Bulgar advance down the plain towards Kilkish they could stop the enemy with their 75's alone. For the function of our division was that of the stopper in the neck of what was known by the French as the "trouée de Kukus." The idea was that on either side the French were pushed forward and held hill positions that formed salients, while, in between, was the inviting flat plain of Kilkish, down which the enemy, if he felt like an offensive, might come,---only to run into our division, behind its wire, at the head of the gap, while the French shot at him from either side.

But the Bulgar was not to be tempted. In fact his whole campaign has been a defensive one, conducted, thanks to his German masters, and their undivided authority, with unvarying skill. The Bulgar has got nearly all he really expected out of the war, and he is content to sit tight on it. He is a stubborn fellow, top, in defence of his possessions.

The chassé-croisé of our divisions with the French was over by the time the Bulgar offensive against the Serbs, which culminated in the battle of Ostrovo, began. It was ending, indeed, when the Serbians first began to move out of Salonica at the end of June.

The holding up of the Bulgar offensive on the Allied left wing at the battle of Ostrovo (related in Chapter X) was followed by a lull, which lasted until the middle of September. The Bulgars did not retire; they and the Serbs sat and looked at each other from behind their stone parapets, which ran about the hillsides, where it was too rocky to dig trenches, in a way that resembled those loose stone walls which divide the fields in North Wales. I say "looking at each other" advisedly, for the Serbs, at any rate, were extraordinarily casual in the way they exposed themselves. "Just stand up here," a Serbian officer would say. with the whole of his head above the parapet, when you visited their front-line trenches. "You see that line of grey stones about 100 yards down the hill? That's their front line. Now just watch the edge of that, and you'll see their heads show now and then. There! See that one?" One always professed to detect a head very quickly, this entertainment being trying for the nerves, but I have often noticed that the Germans have not taught the Bulgarians to be anything like as good at sniping as they are themselves.

From July 20th, however, the British force began to settle down into position, from the Vardar in the centre of the Allied line round by Lake Doiran and the Struma to the sea---a front of ninety miles.

The French, at this period of midsummer, 1916, had no actual sector. Some of their troops were getting into position on the left flank of the Serbians to begin the push backwards towards Monastir, and they had two divisions in Army reserve, available for reinforcing any part of the front. While we were still in process of relieving the French, we co-operated with them in seizing some hill-positions in the corner by Lake Doiran, which carried the Allied line forward to the foot of those heights of the "Pip Ridge," Grand Couronné and Petit Couronné, which have since barred our further progress.

The enemy forces between the Vardar and Lake Doiran now consisted of three German infantry battalions on the left bank of the river, with two others in reserve at Bogdanci, and sixteen Bulgarian battalions on the rest of the line as far as Doiran, with several others in reserve.

On August 15th the French infantry, supported both by English and French guns, occupied Tortoise Hill and the village of Doldzeli. Next day, and on the night following that, the Bulgars violently counter-attacked Doldzeli, and the village changed hands several times, finally remaining neutral ground, with the opposing forces entrenched on either edge of it. To support this French force in its new position. the Oxfords and Bucks Light Infantry rushed Horseshoe Hill in the night of the 17th with the bayonet. The French originally proposed to go on and attack Petit Couronné, then less formidable than it is now, all these offensive movements being intended but as the prelude to a strong French thrust up the Vardar valley, as has been related in Chapter X. But just then came the sudden Bulgar offensive southwards from Monastir, and operations of any scope in the Doiran-Yardar sector had to be called off, so that all available strength might be used to meet the danger on the left wing.

On September 11th, a couple of days before the date fixed for the start of the combined push which the French, Serbians and Russians were preparing to make from Lake Ostrovo, the British, to co-operate with this movement, began a holding attack on the Macukovo salient close to the left bank of the Vardar. This salient was very thoroughly fortified, and was, moreover, held by German troops. We began with three days' artillery bombardment by all calibres, using heavy howitzers and field-howitzers to smash the enemy trenches, field-guns to cut their wire, and 60-pounders and long 6-inch guns to silence the enemy's artillery. On the night of the 13th, the infantry attack was made. It began by officers' patrols creeping up to find the best gaps in the wire. The length of front on which we were attacking was only a mile, for our object was not to pierce, or even permanently to occupy part of the enemy's front, but merely to seize, and, if possible, hold for a little time the position called "Machine-gun Hill," with a view to keeping the Bulgars interested in this part of their front, and thus preventing them from sending reinforcements round to oppose the impending Franco-Serbian attack in the west. It was the first time our troops in the Balkans had made an attack of this size upon entrenched positions of the enemy, but in one hour and twenty-five minutes from the time that the order of attack was given at the place of assembly, the whole of the trenches indicated were in our possession. Fifty prisoners with nine machine-guns were taken, and the Lancashire Fusiliers and Liverpool Regiment, supported by the East Lancashire and R. W. Fusiliers who had captured the position, began at. once to reconstruct its defences. Not without reason, for the Bulgar infantry counter-attack, which they beat off during the night, was only a prelude to a most violent bombardment next day by every Bulgarian battery within range. The next afternoon, in consequence, to avoid further losses, and as the limited object of the attack had been fully carried out, the brigade was withdrawn.

Meanwhile, the Franco-Serbian counter-offensive had started, and met with very satisfactory success. The Serbs had in line the whole of their Third and First Armies under Generals Vassitch and Voivode Misitch respectively. Their Second Army remained where it had been since before the Ostrovo battle, further round on the right, facing the Bulgars, among the steep scrub-covered mountains of the Moglena. And in co-operation with the Serbs, at the northern end of Lake Ostrovo, was practically the whole French force in the Balkans, with a contingent of Russians. The Serbs were also supported by French heavy artillery, having no guns of their own bigger than 120 mm.

I returned immediately after witnessing the attack on the Macukovo salient to the Serbian front. By this time, September 18th, the Franco-Serbian Army had pushed forward to within a few miles of Florina on the left wing, their new line running in a northeasterly direction from there back towards Kaimakchalan. The Serbs took back thirteen miles of lost ground in three days. The Gornichevo pass and the village of Banitza, on the main road to Monastir, had, been regained, and as you drove along it, you passed ample evidence that the Bulgarian retreat had been considerably hurried. Abandoned guns, to the number of nine, and thirty limbers, lay by the side of the road. The victorious Serbs had not yet had time to drag them away. All the rubbish that a hastily retreating army leaves behind was scattered right and left. Bullet-pierced caps and helmets, greatcoats, broken rifles, ammunition-pouches, marked the trail of the retreating enemy, and from the top of the hill at Banitza, where the road drops steeply down to the plain, you could see the Serbian infantry spread out on the green turf, each in his little individual shelter-trench, while the enemy shrapnel burst above and among them; and beyond, right away in the distance, loomed faintly the white minarets and walls of Monastir, their goal on the threshold of Serbia, gleaming faintly through the haze, like the towers of an unreal fairy-city. There was to be much fighting during the next two months in this green plain of Monastir, across which the enemy had already constructed two strong lines of defensive works before he started on his advance to Ostrovo.

And this is the moment to say how effective a contribution towards the success of the Serbian advance from Ostrovo was made by the English M.T. companies, which had been lent to the Serbian Army, the Serbs having no M.T. organisation of their own. If I remember rightly, there were at this time three Ford companies of 100 lorries each, and one three-ton lorry company attached to the Serbians. Serbian generals have frequently avowed in their Army orders how impossible it would have been for them to press so closely as they did upon the heels of the Bulgars but for the self-regardless assistance of the officers and men of these M.T. companies. The drivers threw themselves into the work of punching those little Ford vans up appalling hills like the Gornichevo, pass in a truly sporting spirit. It was up to them to see that the Serbians fighting on ahead were not let down for lack of ammunition, and that as many of their wounded as possible should be brought back down to railhead at Ostrovo. They worked for forty-eight hours on end without stopping, over roads crowded with troops and guns, cheerfully giving up food and sleep during the push. Some of the gradients up which they took their loads were so steep that the petrol would not flow into the carburetter, and the only way the cars could get up these parts was by a sort of waltzing movement, the weary but determined driver twisting his van sideways across the road every few yards to get another gasp of petrol, and then making on up the slope a little further until his engine was on the point of stopping, before repeating the manoeuvre. Perhaps the worst of the many bad runs which these Ford companies undertook, was the one from the side of Lake Ostrovo up to the village of Batachin on the slopes of Mt. Kaimakchalan. I made one journey up it, and though it was once my fortune to chase an aeroplane across the Swiss Alps in a 100 h.p. racing-car, climbing Kaimakchalan in a "flying bedstead" of a Ford was a sensation yet more vivid. As the car zigzagged up the hairpin ladder of the yellow road, one was haunted by an incongruous memory of how

The blessed Damozel lean'd out

From the gold bar of Heaven."

For, indeed, one might have been on some celestial balcony. Ostrovo Lake, with its ragged fringe of trees, and the sandy flats upon its shore, lay far below, almost sheer beneath one. And looking down upon the roofs of the next convoy of cars following, they seemed more like an orderly string of ants than of vehicles as big as one's own.

There is a belt of splendid beech forest halfway up Kaimakchalan, but beyond that the bare mountainside stretches nakedly on to its cap of almost perennial snow. Its surface is like Dartmoor drawn up at an angle to the sky, and right on the top, where the north slope drops sheer away to the Cerna valley, stand the white frontier-stones that mark the boundary of Serbia. From here there is a magnificent outlook across a great confused stretch of rocky hills which from this height appear no more important than the wrinkles on a plaster contour-map.

It was on this vantage-ground above the clouds, with the country they were fighting to win back laid out in full prospect before their eyes, that the Serbs fought their fiercest battles with the Bulgars. The Bulgars had such casualties that one battalion of their 46th Regiment mutinied. Little entrenching was possible on the stonebound mountain-side. In clefts and gullies, behind outcrops of rock, or under shelter of individual heaps of stones collected under cover of the dark the soldiers of these two Balkan armies, not unakin in race, with language closely related, and histories that are a parallel story, faced and fought each other with savage and bitter hatred, under the fiercest weather conditions of cold and exposure. The wind there was sometimes so strong that the Serbs said they "almost feared that the trenchmortar projectiles would be blown back onto them."

There could be little artillery at that altitude to keep the battle-lines apart. Mortar, bomb and bayonet were the weapons that worked the slaughter on Kaimakchalan, and so fiercely were they used that Serbs would reach the ambulances with broken-off pieces of knives and bayonets in their wounds. You came upon little piles of dead in every gully; behind each clump of rocks you found them, not half-buried in mud or partly covered by the ruins of a blown-in trench or shattered dugout, but lying like men asleep on the clean hard stones. The fish-tail of an aerial torpedo, the effect of whose explosion had been magnified by flying clouds of stony shrapnel, usually furnished evidence of the nature of their death. Not for days only, but for weeks after, dead Bulgars lay there, preserved in the semblance of life by the cold mountain air, looking with calm, unseeing eyes across the battleground that had once been the scene of savage and concentrated passion and activity, and then lapsed back again into its native loneliness, where the eagle is the only thing that moves. Some still held in their stiff fingers the bandage they had been putting to a wound when death took them; here was a man with a half-eaten bread-crust in his hand. On others you could see no sign of hurt. They must have been killed by the shock alone of the explosion of that aerial torpedo whose black fragments lie among them,---killed, too, at night probably as they waited for the dawn to start fighting once more. In other places you would find bodies of Serbs and Bulgars mixed together where they had met with the bayonet. Yet on none of the dead faces that you looked into did you see the trace of an expression of anger or fear. They slept dispassionately, calmly, as if finding in death the rest and release from suffering that war had so sternly denied them.

Meanwhile, in the broad corridor of flat green turf that leads northward from Florina to Monastir, the Serbs and French fought unremittingly to drive the Bulgars further. Delay was caused to our advance by the fact that the Bulgars in their retreat blew up the railway viaduct across the gorge at Eksisu; and the need of pausing while the French wheeled round into line at Florina to conform with the right-angled change of direction necessary for the advance on Monastir allowed the enemy time to settle into his Kenali trenches, which held us up for six weeks more. A preliminary Bulgar stand was made on a line that ran through Petorak, Vrbeni and Krusograd.

It was open fighting in the fullest sense of the word. From the crest of one of the rolling ridges of grass you could watch the movement of every individual infantry soldier from the time he got up at the, foot of your hill, through all his two-mile advance in skirmishing order across the bare plain, until he reached the enemy wire, which was clear to see with glasses in front of the black copses of trees that surround the villages of Petorak and Vrbeni.

Once during that fighting, on September 19th, I saw a Bulgarian attempt at a cavalry charge. It was only an affair of two squadrons, and it was swept away by machine-guns, the body of the young captain who led it being found afterwards on the ground. But cavalry charges are rare now, and an open flat country like this plain of Monastir, where you could gallop till your horse dropped dead without meeting any obstacle more formidable than a drainage-ditch, was a rare setting for one. The Serbian infantry were scattered in the open, not in a continuous trench-fine, but in those little trous individuels, like the beginnings of a grave, which each man digs for himself . The Bulgar guns were shelling them with shrapnel in a half-hearted way. It seemed a slack sort of battle day. Then one noticed an indistinct little black blob moving about on the edge of Vrbeni wood four miles away. The glasses revealed it as horsemen, formed in two separate bodies. Could it be that they were going to charge? Evidently, for they began to move towards us, keeping their close formation for a little, then opening out onto a wider front. They trotted on a little distance in this way, with shells beginning to drop in their direction from batteries which had noticed the unusual phenomenon. The trot broke into a canter and then the two squadrons suddenly strung out into another formation, a long diagonal line, and lengthened into a gallop. It was a gallant sight, and when the Serbian machine-guns began a rattling fire that eventually stopped the charge, one's sympathy seemed drawn somehow to the horsemen. For one thing a mounted man coming down is much more dramatic a sight than a foot-soldier falling. Horse and man, if it is the horse that is hit, go sprawling and rolling over, or if the man is shot and falls from the saddle, the horse either comes galloping on riderless or else rushes wildly away on his own; whereas, when you watch an infantry advance, you cannot tell which men are dropping because they are hit and which are only taking cover or lying down to get breath. Those Bulgar horsemen never got up to the Serbian infantry. As soon as they were within a thousand yards, the leading files of the diagonal lines withered away before a hail of bullets from rifles and machine-guns; they could never have seen the troops they had been sent to attack, and indeed the whole thing seemed a very futile and unpractical sort of enterprise to have undertaken at all. What was left of the two squadrons frayed out into a line that became more and more ragged till it just broke off, and the survivors, wheeling round, galloped back for Vrbeni wood again.

The right use for cavalry in modern war was shown a little later when the Serbs forced the passage of the Cerna river. That was part of this same battle for Monastir, but occurred when we had got a little further forward and the Serbs were pushing on to the right of the town so as to threaten the enemy line of communications and force him to abandon the place.

The continuous trench-line which the Bulgars had built across the plain of Monastir ran in front of Kenali, and then mounted a conspicuous sandstone bluff forming the left bank of the Sakulevo river, the line of which it followed till it reached the Cerna at Brod. East of Brod the Cerna, hitherto open on one bank to the flat plain of Monastir, enters a valley between rocky mountains as it begins to turn north again. On the corner which the Starkovgrob heights make on the southern bank of the river, like a high bastion looking out over the Monastir plain to the west, and across into the welter of stony hills beyond the Cerna to the north, the commander of the Serbian Morava division had fixed his battle observation-post. There you could stand among pinnacles of rock and watch every move of the fight across the valley. Alongside you, concealed by the crags, French fieldguns pounded the stony heights that rose like an unbroken wall beyond the river, where, dotted about among the huge boulders, you could see the Serbian infantry clambering upwards to the assault. To make their horizon-blue coats more distinguishable against the slate-coloured rock, so that the French gunners and their own should not drop shells among them, every man had a square of white calico fastened to his back, and the leader of each section carried a little flag, so that the steep slopes opposite were dotted with moving points of white.

Brod, the village on the river-bank, was burning, and had been abandoned by the enemy. Veliselo, the squalid little hamlet above it, hiding in a pocket of the mountains, was the Serbians' next objective. And suddenly, as we watched the Serb infantry climb upward among the rocks with their screen of friendly shells creeping on ahead of them, a number of little black figures sprang into sight on the hillside above and went racing off among the rocks towards Veliselo. It was the Bulgars in retreat. And soon Veliselo itself, whose thatched mud huts were plainly to be seen, began to show signs of panic-stricken activity. A string of Bulgarian carts started pouring out of the further end. With your glasses you could see stragglers running into the villages, dodging about among the houses and then out along the track beyond, on the trail of the retreating column. The Bulgars were in full flight for their next prepared position among the mountains behind. To cut off as many as possible before they got to the protection of the new line the commander of the Morava division ordered up the Serbian cavalry. They appeared from behind us down in the plain below on our left, ---a long column trotting and cantering alternately in a dry stream-bed. While they followed that the Bulgar and German gunners on the rocky slopes beyond the Cerna could not see them, but soon they had to leave it and strike for the river-bank across the open. It was a splendid spectacle,---a half-mile column of horsemen cantering over the grass. Shells began to fall about them, now on this side, now on that. One or two men fell, hit by flying fragments, but the rest swept on and crossed the Cerna with a mighty splashing. Brod , the village on the other side, was already on fire, and a bombardment of it was begun by the enemy to hinder the Serbian cavalry from passing, but they formed up under the cover of the river-bank and then squadrons began to set off on individual adventures after the flying Bulgars. One of them captured a whole enemy battery, limbers, gun-teams and all.

While the Serbians were thus fighting with gradual success upon the right of the Monastir sector, the French made one or two frontal attacks upon the Kenali trenches in the flat plain, and the Russians had some rough fighting among the mountains that stretch westwards to Lake Prespa. These attacks, of which the chief was that of October 14th, were not successful, for the Kenali lines were made with all the skill and thoroughness of positions on the Western front, while we had nothing like the same weight or quantity of artillery at our disposal to smash them. So that when the Serbs carried Kaimakchalan and began to get on in the loop of the Cerna river on one flank of the Kenali lines, in such a way that if they won much more ground they would succeed in turning the defences of Monastir, General Sarrail withdrew troops, both French and Russian, from his left wing to strengthen his right, and put these French reinforcements under the orders of Marshal Misitch, commanding the Serbian First Army, who proved worthy of his confidence. The tactics which led finally to the recapture of Monastir were, in fact, manœuvring and pressure along the whole of this sector, combined with a definite attempt to pierce the enemy front at one point, this effort being made by the Serbs, to whose persistence under most severe fighting conditions the credit for this winning back of their own city belongs.

While our Allies on the left were engaged in this heavy fighting, the British Army on the Struma undertook an attack upon some fortified villages on the other side of the river. The main object of this was to hold the Bulgars in front of us and keep them from sending troops round to the Monastir sector to strengthen the resistance to our Allies there.

When you have journeyed about forty miles up and down the hills of the winding Seres road you come to the crest of the last ridge and find yourself looking across the broad green Struma valley, on the far side of which, fifteen miles away, the white houses of Seres shine out from among black trees at the foot of the opposing hills.

Further to the left, also under the slope of the ridge opposite, is Demir Hissar, and there, where the river comes down from the north into the plain, is the only break in the heights that close the view before you; that break is the pass of Rupel, where stands the now-famous fort. To the west again of this rises the black wall of the Belashitza mountains, capped with snow far on into the spring.

The plain of the Struma at your feet looks from this height flat as a billiard-table, but is by no means so level, for its surface is scored with little nullahs, dried-up stream-beds, and sunken roads that make it quite difficult to find your way about when you get down there. You can often see only a few yards on either side of you; every track looks alike; every tree is the twin model of every other. The villages scattered about the plain are recognisable enough from up here, but down there if you have lost your bearings a little and approach one of them at close quarters, there is nothing in its single-storied, tumble-down, dingy-white plaster cottages to distinguish it from half-a-dozen others, and moreover they are all so straggling that troops told off to occupy a village were often hard put to it to tell where it ended and the next one began.

The Struma river, here gleaming like a silver band across the grass, there hidden by black clumps of trees, is the explanation both of why this is one of the most fertile stretches of ground, yard for yard, in Europe, and why it is also one of the most dangerous malarial belts in the world. The best cigarettes you can buy in, Piccadilly are probably made of tobacco grown on the fields through which we have since cut our trenches. That is one of the reasons why they are now so dear. Before the Bulgars moved down and we moved up to the Struma the Seres road would be dotted with strings of donkeys laden with bales of pale gold tobacco-leaf, coming down to Salonica for shipment. A fair but unhealthy region, which I will describe more fully later on.

What we were setting out to do beyond the Struma was to expand the small existing bridgehead beyond Orliak bridge into a big crescent of new trenches, including within its limits several villages which we now prepared to capture. The two which were gained on September 30th are called Karadjakeui-bala and Karadjakeui-zir.

During the previous night two brigades of one division and the 29th Brigade of the 10th Division crossed the Struma below Orliak bridge and by 8 AM the Gloucesters and Cameron Highlanders had taken Bala, meeting with little opposition.

Zir, the next objective, was only a mile away across the open and at 10.20 A.M. the Argylls and the Royal Scots were about to push on against it, when from the village of Yenikeuy, next to the west, the head of a Bulgar counter-attack appeared. It. was made by one regiment, but it got a very little way. The heavy guns of another division whose artillery was co-operating, smashed it up at once; the Bulgars could be seen falling fast and the rest soon turned back and were lost to sight.

The unusual feature of this fighting on the Struma was the remarkably good artillery observation you could get. From the artillery command post on one of the foothills at the edge of the plain one saw everything. Our men and the enemy were equally visible, and the work of the British artillery was even better than usual in consequence.

The attack on Zir was delayed for a time by an enemy trench which enfiladed our troops as they advanced, and it was decided to renew the attempt at four, beginning with an intense bombardment of the village.

Never did a battle look more like a chess-game than from this hill.. The Corps Commander and his staff were standing there among the scrub. A deal table behind them was covered with maps.

On another hillock the artillery general had his command post. New white telegraph poles brought a criss-cross of wires to it; a battery of telescopes of all calibres were directed to different points of the valley below. At the telephone a gunner staff-officer was ringing up different batteries all the time. "Is that the Adjutant? What reports have you about ammuntion? What's the bearing of that gun?---5730 magnetic, did you say? What's that? Enemy convoy proceeding along road to Hristian Camilla? Right. Tell one-four-three to get onto it. "

A moment later he would be talking to the 6-inch howitzers, squat guns with caterpillar-wheels, lurking in depressions of the ground at the foot of the hill, and looking, under their roof of anti-aerial-observation fish-netting, like some strange and gigantic fowl in a pen. "Are you there? You are to stop firing now until four o'clock. At four you are to start shelling Zir one round a minute. Then at 4.10 whack in all you can everywhere round about and inside the village. Now what time have you got? The infantry are going to try to rush the village at 4.15. Not a round is to be fired after that time. It's now 3.48. Pass that round to the batteries." And a few minutes later, "I want to synchronise your watch again. It's 3.56,---three-five, four-oh, four-five, five-oh, five-five, 3.57."

Then an officer at another telephone would interrupt, "Oh---Esses-Beer reports enemy troops advancing from Yenikeui north-east, sir."

All glasses are converged onto Yenikeui. "I can see a few," says some one. "Yes, they're advancing from the N.E. There are some in the middle of the village, too. Lot of single men behind. Now, there's a man on a horse behind. By Jove, it isn't a man on a horse. It's a gun. Well, they're not moving. I wonder if they're dummies. They put up very clever dummies sometimes."

But the pulverising of Zir was the most pressing business on hand. The chatty arrangements one had heard made over the telephone had conjured up hell for Zir and ordered it punctually to the minute. Every calibre of gun we had, big middling and small, concentrated on that 400-yard front of village and with each single second half-a-dozen fountains of parti-coloured dust and smoke sprang up along it simultaneously into the air. Grey smoke, black smoke, yellow, brown and white, elbowed and overlapped each other. Fierce red flames flashed among them, dulled by the inferno of smoke. Fleecy shrapnel bursts grouped themselves in bunches overhead. By this time not a house in the village could be seen.

There was not a gap between the shell-bursts. Zir was literally hidden behind a dense curtain. Until at last the very smoke itself was hidden by more smoke, the outlines of individual shell-bursts being engulfed and swallowed up by a formless fog of drifting yellow fumes. Then, in the same manner as the bombardment had begun, it stopped, as suddenly as you turn off water at a tap. Three hundred and thirty 6-inch shells had fallen into the village in the last five minutes. Then Zir slowly emerged again, but smashed and battered into a shape that its oldest inhabitant would not have recognized, with sluggish drifts and wisps of lazy smoke crawling through its narrow streets.

It was next the turn of the twin village of Bala, which we had newly won, to endure temporary smoke-eclipse, for the Bulgars, expecting our attack, put up a violent curtain of fire. The two villages were linked by a mile-long bar of brown smoke and dust. Through this at five o'clock the Royal Scots and the Argyll and Sutherlands pushed on, as fast as man can move, carrying two days' rations, pack, rifle, 220 rounds of ammunition, and pick or shovel. They were still enfiladed by machine-guns, but found the Bulgars in poor trenches on the outskirts of Zir. The enemy stood their ground till our men were close upon them, then threw down their arms, and Zir was ours. Just after dark, however, a Bulgar counter-attack was launched, and the black plain sprang into a vivid illumination of coloured glares and "Very" lights. Another attack broke loose at 1.15 A.M. It was a pitch-black night with a sickle moon just peeping over the hills. For five minutes nothing but small arms were at work. Then one solitary green ball of fire shot up and drooped slowly down again. Immediately the waiting Bulgar guns opened and the whole darkness round Zir was torn by flashes of bursting shells. The flare of the discharges flickered across the sky like summer lightning. From the trenches where our men were firing as fast as they could work the bolt, brilliant white "Very" lights followed one another into the air like a Roman candle display and threw their circles of pale cold radiance upon the bare grass dotted with dark Bulgar forms. On their side, too, red and green flare-signals towered up unceasingly for the guidance of their energetic guns. Then our people brought our own artillery to work, though in less measure, and 5-inch shells, which hurtle across the sky with the noise of a tube train approaching a station, began at deliberate intervals to burst upon the rear of the Bulgarian attack. It was a fierce onslaught, but it failed, and when dawn came, cold and grey, Zir and Bala awakened side by side looking as sleepy as they had always done, with nothing at first sight to show that this particular morning they were the centre of a violent battlefield.

Strange are life's little contrasts, especially in war. During the most eventful part of that afternoon's fighting, when the whole plain below was tumultuous with devastation, there was an officer's soldier-servant sitting behind the hill from which I was watching, on a cushion taken from a car, making tea for his master at a little spirit stove, skimming the pages of an old monthly magazine, and whistling Tosti's "Goodbye," or playing with a stray mongrel dog, without the faintest sign of any knowledge that such a show of life and death was going on within easy view over his shoulder.

Zir and Bala having been won, it remained to capture the big village of Yenikeuy, which stands on the main road from the Orliak bridge to Seres. At 5.30 A.M., on October 3rd, the 6-inch guns fired thirty-five salvoes into the village. Then they lifted from its front edge and swept through it. The field-guns proceeded to repeat this process exactly, and after them the Royal Munsters, and Royal Dublin Fusiliers entered with little opposition.

But immediately a very strong counter-attack started out from Topolova. At least three battalions took part in it, and the long lines of men coming on across the open were an impressive sight. But they never got within rifle range, for as soon as they could be reached with the heavies they had 6-inch shells bursting among them.

They persevered awhile, for the Bulgar is a stubborn fellow, but when the field-artillery opened on them with shrapnel, they turned first south, then east, then broke up and fled into the shelter of the nearest nullahs and the last seen of them was a line of men disappearing into Kalendra. One more counterattack was attempted a little later and driven back in the same way with heavy loss.

But at 4 P.M. the Orliak bridge and other bridges upon which we were dependent for bringing up reinforcements were heavily shelled by some enemy heavy batteries which now first came into action, and at the same time a particularly determined counter-attack by six or seven battalions advanced upon Yenikeuy and succeeded in reoccupying the northern part of it.

The garrison of the village was stiffened by another battalion sent up from the river-side, and heavy fighting went on all night, which finally secured for us undisputed possession.

This attack on Yenikeuy had been a field-day, too, for the armoured motor-cars, four of which were given a run across the Orliak bridge in the morning, and did some useful work with their machine-guns, coming back with their tires all ripped and flattened by enemy rifle-fire.

Next morning the Bulgars evacuated Nevolyen village after artillery bombardment alone. Hristian Kamila, too, was evacuated. The bridgehead which it had been intended to create was now complete, and the Bulgars withdrew the greater part of their force behind the railway, though they left a strong garrison in Bairakli Djuma.

They were indeed thoroughly discouraged. Their 7th Division had lost a third of its fighting strength. The 10th Division, brought up from Xanthe, had also suffered heavily. Our burying parties dealt with 1,500 Bulgar corpses. At a moderate estimate their losses must have been 5,000. Three hundred and seventy-five prisoners and three machine-guns were taken.

We could see Bulgar columns marching off towards Rupel, and it almost looked for a while as if they might be going to abandon the Struma valley altogether.

A still larger operation on the Struma was carried out on October 31st, in the sense that we had more troops engaged than at any one time before. in the Balkans. Attacks were made at about half-a-dozen points along the fifty-mile-long Struma front. Some of these were only intended as demonstrations, the main objective being the strongly fortified village of Bairakli Djuma, which stands on the way to the entrance to Rupel pass. Three new bridges had been built across the Struma for this attack, and on the night of the 26th the villages of Elisan, Ormanli and Haznatar were seized without opposition as a taking-off area. The attack on Bairakli Djuma was then ordered and carried out on the morning of October 30th-31st, with small loss, thanks to a daring deployment of three battalions on the west of the village, which, though exposed to attack from the flank, was entirely successful. The scheme was that three battalions should deploy and attack the village from the west, while one company with three Vickers guns demonstrated and held the enemy to the ground on the south, the remaining three companies being held in brigade reserve at Ormanli.

The plan worked well, the King's Own, East Yorkshires and K.O.Y.L.I. attacking from the west, while a company of the Yorkshires and Lancashires demonstrated so successfully on the south that most of the enemy knew nothing of the flank attack until they were surrounded and their retreat cut off. The total of prisoners taken by this surprise attack was three officers and 320 other ranks, while one officer and seventeen other ranks were found dead. Our troops, in taking the village, only had one killed and three wounded, though the subsequent enemy shelling brought our casualties up to five officers and forty-eight other ranks.

.

AS November drew on the heavy autumn rains converted the trenches in the Kenali plain into a swamp of the utmost wretchedness. There had been no progress there, but meanwhile the Danube Division, among the snow on the heights in the Cerna loop, had taken first Polog, then Iven, and finally got up half-way the steep side of Hill 1212, one of the main positions in this confused tangle of mountains, which, however,---as is the heartbreaking way of the Balkans,---is dominated in turn by the next height, Hill 1378.

On November 14th an offensive was ordered along the whole line from Kenali to the Cerna. Two brigades of French infantry attacked Bukri and what was now the Kenali salient at noon. Three bayonet assaults were met by such heavy machine-gun fire that they failed; but at 2.30 the attack was renewed, and two Bulgar lines at Bukri were carried and held against two counter-attacks,---all this in teeming rain, penetrating cold and the worst mud conceivable. The result was at last to force the Bulgars out of the Kenali line, which they had held for two months, and back onto the next prepared position on the Bistrica river, five miles behind, towards Monastir. Twenty four pieces of artillery were taken from the enemy in three days.

The Serbs made prisoners in this fighting no less than twenty-eight German officers and 1,100 other ranks,---a big haul for the Balkans, where the Germans are used only as stiffening for especially threatened positions. These captives cursed the Bulgars freely, saying that they had bolted and let them down.

On November 17th, the Serbs carried both Hill 1212 and Hill 1378 beyond. On that, two days later, without further pressure, the Bulgars suddenly left the Bistrica line and abandoned Monastir itself, falling back down the road to Prilep.

Like many things long and earnestly awaited, the evacuation of Monastir finally came as something of a surprise. It seemed when the winter rains and snow began as if we should hardly get there before the spring. Even the night before the city was actually evacuated, when I was riding back to Vrbeni from a visit to the Serbian sector of the front with some English staff-officers, and we saw an enemy column marching out of Opticar village on the Bistrica, while earlier in the afternoon we had also noticed a string of waggons crossing the Novak bridge to the other side of the Cerna, it only seemed as if the Bulgars were moving troops from their centre to reinforce their hard-pressed left. I slept that night in a shell-riddled house in Vrbeni, which I had shared with some French officers, who had moved on since the Kenali lines had fallen. It was a dingy, rickety place, its shattered windows carefully patched with sheets of German maps and a pencilled screed on one of the doors to say that it was "reserved for three staff officers of the map-making section of the Staff of General Mackensen's Army."

Next morning, wading out into the river of fluid mud which served as the main street of Vrbeni, I met a Serbian cavalry officer on horseback, clearly in a mood of some excitement, who waved his hand and shouted: " De bonnes nouvelles! De bonnes nouvelles! Monastir is taken; the town is in flames!"

It was not the first time that people had assured me with equal emotion of the capture of Monastir, but though one still felt doubtful it was the least one could do to go and see. So the mud-caked Ford car was turned out with all speed and I started along the well-known and terribly bad road that led towards Monastir,---twelve or thirteen miles ahead.

As usual, the road was crowded with every sort of transport, from creaking, solid-wheeled, bullock-drawn ox-carts that the supply service of Charlemagne's army might have used, to three-ton motor-lorries, skidding and splashing through the mud. On either side were spread camps and bivouacs and dumps and depots of every kind; heaps of carcasses of meat, mounds of petrol-tins, piles of long black cylinders of gas for the observation balloon, timber, tin, wire, carefully scattered supplies of ammunition.

One thing caught the eye at once as the presage of a day that would live in history. The most perfect triple rainbow I ever saw hung over Monastir, spanning it in a brilliant arch of colour. One foot rested on the mountains to the west, where the Italians had been fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Russian and French troops in the plain; the other was planted on the rocky heights beyond the Cerna, from where the Serbs, worn by much hard fighting, were looking down upon the city which their dogged determination had done most to win.

As one got nearer to what the night before had been the enemy's line on the Bistrica, the Monastir road became less and less thronged. And here the ability of the German road-engineers forced itself upon the attention by a remarkable contrast. Presumably there had been as much traffic along the road up to their front line as along that which led to ours, and the weather had certainly been the same for both. Yet, while our part of the Monastir road had a surface like rock-cake covered with mud of the consistency of porridge, directly you passed into what had been, until that morning, the German lines, you found yourself on a hard, smooth surface as good as an English road at home.

I got to Monastir at eleven. The first French and Russian troops had marched in together at nine, three-quarters of an hour after the last of the German rearguard left the town.

The enemy retreat had been skilfully arranged. At three o'clock in the morning the sentries in the new French line opposite the Bulgar trenches on the Bistrica had seen a great fire start in Monastir. It was the barracks, which the enemy had set burning. Then a little later, the French patrols reported that the enemy front trenches had been found empty in several places. The Bistrica line was accordingly occupied along its whole length, the Russians wading the stream breast-high, and the Allied Force began to feel forward to get into touch again with the retiring enemy.

By seven o'clock, the advanced patrols reported that the town seemed unoccupied. They were then at a distance of two miles from it, and as Prince Murat, a young French cavalry officer and descendant of Napoleon's general, at the head of the mounted scouts of his regiment, approached the town at 8.30 A.M. he caught sight of the last German battery left to protect the retreat limbering up and making off at the trot.

At first it scarcely seemed as if there were any civilian population in Monastir, but they were only hiding in their shuttered houses, and when the French marched in many of them came out and threw flowers or hung up French and Serbian flags, which they must have hidden somewhere all the twelve months the enemy was there. The British consulate flag,the Union Jack with an official "difference" in the centre,---had been tucked away in a mattress all that time.

I turned into what used to be the "Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Consulate" in the main street of the town. In the hall, littered with broken packing-cases and other signs of hurried departure, were two placid-faced French Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul, with their white-winged headgear as stiff and spotless as if they were in a peaceful French country town instead of a newly captured Macedonian city. They had come there to try and reclaim their piano which some German officers had commandeered and carried off to their quarters at the consulate.

The nuns said they had organised a hospital at their convent which had been under the supervision of German medical officers; seventeen dying Germans had been left behind in their charge when the army retreated the night before. "The Germans were correct but brusque," said one of the sisters. "The Bulgars were---" and she made an expressive little grimace.

Twice before, they said, the Germans and Bulgars had made all preparations for abandoning Monastir. The first occasion was on September 17th, after the retaking of Florina. That was followed, however, by the delay necessary for the slow wheeling round of the French and Russians into line with the Serbians again, facing the north, a manoeuvre that had to be carried out with caution, so as to give the enemy no chance of thrusting himself into a gap between them. So the enemy took heart once more.

The second time the Bulgars had been ready to leave Monastir was on October 4th, after the capture of Petorak and Vrbeni and the thrusting back of the Bulgars to the Kenali lines.

Finally, the army's doctor in charge of the nuns' hospital had gone to Prilep on November 18th and telephoned from there at three in the afternoon that the hospital was to be evacuated and transferred to Prilep that night.

There is no doubt that the enemy was thoroughly discouraged and, for the moment, beaten. Nothing less would have caused the Bulgars to abandon Monastir, the sign and token of that dominion in Macedonia which they covet. Had the Allies disposed of fresh troops to carry on the pursuit, we might have taken Prilep too, and pushed the enemy back into the Babouna pass on the way to Uskub. All that the Bulgars left behind was a rearguard on the Prilep road, about three miles out from Monastir, to cover their retreat. But when they saw that the French, Serbs, Russians and Italians were all equally exhausted, that we had not a single fresh division with which to press upon their heels, but that the same wearied troops, their effectives often reduced by three-fifths, who had been fighting for six weeks in the mud before Monastir, were now hurried straight through the town and thrown into action again beyond it against the enemy rearguard, they took heart and began to hold on in greater force to the semicircle of hills which dominates Monastir from the north. They had conceived the idea of keeping the town within shell-range and making it as far as possible uninhabitable for their foes.

This they have been able to do with effect. For a few weeks after its recapture, Monastir was thronged with troops, supply-depots and the headquarters of various Allied contingents. But the daily shelling of the congested streets made it more and more unsuitable for all these purposes, and now, though the French still hold all the ground they occupied beyond the town to the north on November 19, 1916, the place itself is deserted, the only population left being the poorer class of Greeks and Serbians, who live huddled in their cellars and who would have starved but for the rations issued to them at first by the military authorities and later by the Serbian Relief Fund. It was while superintending this work in Monastir that Mrs. Harley, a sister of Lord French, was killed by a shrapnel bullet in one of the daily bombardments.

All of us who had been on the Serbian front knew and respected profoundly the courage and energy. of this gallant, white-haired lady. And there are not a few other gently-nurtured Englishwomen living, if not in actual danger, at any rate amid dreary, monotonous and squalid surroundings on the Serbian front, in order to bring relief to the population of that much-afflicted region. There are, for instance, the Hon. Mrs. Massey, who was wounded by a splinter from an aeroplane bomb while at her post in Sakulevo, Miss Stewart-Richardson, and several more. The Scottish Women's Hospitals are associated more especially with medical work in the field. They are attached to the Serbian Army and take in wounded in the ordinary way. The Serbians were never tired of expressing their admiration for these plucky, cheery, short-skirted girls, in their grey uniforms, who worked as nurses in the hospitals under the trees by Ostrovo Lake and at the base at Salonica, or drove their little Ford ambulances over the worst roads without any resource to count on but their own.

Poor Monastir! It is the only town in Macedonia for which you can feel any liking; most picturesquely situated, looking southwards down the long green plain, and shielded to the north by the well-tilled slopes of mountains dotted with little white villages. Its streets, though of rough cobbles, are clean. It has a few modern buildings, and the rest are a degree above that dreary, ugly squalor that makes the average Macedonian township so uninteresting. The population is mixed, of course; all Macedonia is a salad of nationalities---a fact which doubtless led some Balkan-travelled cook to invent the name macédoine de fruits. We consequently had some little trouble with enemy agents among the Bulgarian section of the inhabitants. Underground telephone wires were found leading to the enemy positions.

The whole population, in fact, whatever its national sympathies, had to go through the outward signs of sudden conversion when, we came in, for the Bulgars had imposed the Bulgarian language and writing with severity. So all the Bulgarian shop-signs had. to come down and Serbian ones go up. Czar Ferdinand must be jerked out of the place of honour on the wall and a portrait of King Peter put there instead. In the Balkans every one has a picture of his political ruler in the house, as a kind of national emblem. At the time of the Salonica "Revolution," for instance, the boom in photographs of M. Venizelos was tremendous, while hundreds of excellent studio portraits of King Constantine could have been, and doubtless were, bought for their value as old pasteboard by some speculator in the uncertainties of future political developments.

There was one hotel in Monastir for whose plight in this respect I felt real sympathy. I went there to get quarters for my servant, and looking round for the name, saw only splashes of fresh whitewash in the places where you would have expected the sign of the hotel to be.

"What's the name of the hotel?" I asked the Greek proprietor.

He smiled uneasily. "Oh, you will find it quite easily again," he said; "there's the main street just there and you turn up by---"

Yes, I know; but what's its name?

"Well," said the owner, with hesitation, "it hasn't got a name yet."

However, next morning a new name went up. I found a flamboyant fresh gilt sign with the title "Hôtel Européen" being hoisted into place. I then learned the eventful history of the hotel's designation. When the Serbians had won Monastir from the Turks the proprietor had suitably commemorated the event and striven to attract official favour by changing its original name to that of "Hôtel de la Nouvelle Serbie." Three years afterwards, in the same month, the Bulgars had taken the town from the Serbs, and the establishment quickly became "Hôtel de la Nouvelle Bulgarie." Now, exactly twelve months later, the Serbs had recaptured Monastir, and the "Nouvelle Bulgarie" sign had to come down with a run to avoid certain trouble. So the proprietor told me that he had now given up trying to keep in touch with these constant changes of the town's nationality. The need of continually having his sign repainted was eating into the profits of his business, and delay in getting rid of the old one, or an error in tact in choosing the new, might well lead to harsh suspicions of the kind that are disposed of by firing-parties at dawn. So he had decided in future to hedge. Under the sign of "Hôtel Européen" he told me he felt that, for some time at any rate, he could have an easy mind. The armies of conflicting states could stream down the main street alongside, their officers could spend persecuted nights in his dubious beds., without their wrath being still further influenced by indignation at the national sentiments expressed by the name of the hotel. And in the flush of confidence which the unexceptionable yet dignified title of "Hôtel Européen" inspired, I noticed, when I came to pay the bill, that the proprietor had raised his prices for rooms two francs above any other hotel in the town.

Monastir was taken on Sunday, and on Tuesday the Crown Prince of Serbia and General Sarrail went up by special train and drove round the town. On the occasion of this victory, which is indeed the principal achievement of the Salonica Expedition, General Sarrail issued a General Order to the Army, dated from Monastir, and addressing the troops of each nationality in turn. To the British he spoke in terms which showed appreciation of their especially ungrateful role. "Your task," said the French Commander-in-Chief, "has been most thankless. You are on a front which has hitherto been defensive, but you have not husbanded your labours or spared your efforts. You are ready to take the offensive when the order comes."

The confidence new-born in the enemy by the realisation that, though we had driven him out of Monastir, we were too weak to follow him up, was shown by the proclamations their aeroplanes let fall on the town. "People of Monastir," they said, "be of good heart. We shall not shell you or bomb you, for we are coming to retake your city."

Probably with this end in view, a whole German division had arrived as reinforcements on the Monastir front, coming from the Somme. Bulgars had also been transferred here from the Dobrudja.

The fighting around Monastir was now heavy, the French making determined attacks in the attempt to push back the enemy out of gun-fire range, and the Bulgars having received orders, as prisoners told us, not to retreat a yard. They were on Snegovo Hill to the north of the town, on Hill 1248, the scene of many bitter encounters since, and on the terraced brown slopes of snow-topped Peristeri to the west, with the Cervena-Stena ridge running down towards Monastir.

From the lower ridges of Snegovo the battle was a spectacle that lingers in the memory. Below you were the red roofs of the town, broken by the domes and minarets of two white mosques. Above these the Bulgar shrapnel burst from time to time in milk-white puffs, while the dense black smoke of the heavier shells that were intended for the French batteries sprang up all round the outskirts of the place. The French artillery, hidden by whatever feature of the ground afforded shelter, was firing as fast as the guns could be reloaded.

On the other side, higher up Mount Snegovo, you looked plainly into the French trenches on the steep hillside, and beyond them on a further slope, separated from the French by a hidden depression in the ground, were the Bulgarian positions. Once, as I watched the French infantry leap out of their trenches and run forward to the attack, an unusual thing happened. The French had passed from sight into the dip in the ground from which they would be climbing the slope beyond to reach the Bulgar line. And suddenly the trenches they were attacking were outlined by a fringe of black figures, which seemed to start out of the ground, as indeed they literally did, for the Bulgars, impatient to fire more effectively upon the attacking French, and regardless of the shrapnel bursting above them, had sprung upon their parapet and stood there in full view. It was as though the bare slope had been suddenly covered with a forest of black tree-trunks.

Those Bulgar front-line trenches were taken by the French, but lost again later. The bad weather had made aeroplane reconnaissance of the enemy's positions ineffective and the French did not know what strength the Bulgars had concentrated in reserve. These reserves counter-attacked the newly gained position and retook it. Next day, however, November 28th, the French retaliated by shelling the Bulgar front line heavily for a time. The enemy withdrew his troops while the shelling lasted, but then the French sent out strong patrols to make a demonstration, which gave the Bulgars the impression that another attack was about to be made. On this, they rushed up reinforcements and manned the front-line strongly again. The French patrols were then withdrawn and their heavy artillery at once opened an intense bombardment on the Bulgar trenches, which caused very heavy losses among the men who had been crowded into them.

The town of Monastir began to be an uncomfortable place to live in. The Bulgars had been forced to realise that they had no chance of taking it back by a counter-offensive, but the French, on the other hand, were not strong enough to thrust them out of. artillery range. So the shelling of the city, which, for all that, only damaged the civilian population, began to become more regular and more intense. One quarter, which was especially exposed, was evacuated and the refugees crowded into another. There was a grave shortage of food. But it was as yet impossible to evacuate the civilian population owing to the danger of blocking up the road which was the single line of supply until the blown-up culverts and smashed points on the railway could be repaired. To be in a shelled town that is crowded with women and children is an unpleasant thing. An almost continual sound of apprehensive moaning filled the streets while a bombardment was going on, and whenever a shell with a whirr and a crash sent one of the flimsy houses flying into a cloud of dust and charred and splintered fragments the tremulous wail would rise to a shriek of terror.

If it had not been for the Greek threat in his rear, which became more urgent after the Athens street-fighting of December 1st, and led General Sarrail to concentrate troops to meet a possible Greek attack on our communications with Monastir, and particularly if we had had reinforcements to use, the next step after the taking of Monastir would have been a move on Resna to the north-west. Resna is an important depot of supplies, and one of the results of taking it would have been to hamper the enemy's communications with his forces in Albania. But the attempt to realise this scheme had to be deferred for some months more, for, in addition to our inadequate numbers and our preoccupation with the Greeks, the mud and the snow of winter now began to impose their annual immobility, upon the armies in the Balkans.

.

WINTER in the Balkans is always a time of rain overhead and mud underfoot. To move anything heavy, such as a gun, the distance of a mile or two is an affair not of hours but of days, and can very often only be accomplished by enlisting supplementary assistance in the way of additional teams or motor tractors which may be in the neighbourhood on quite different business. For the men in the trenches this weather brings not a respite but an addition of labour, the digging of the dry season being varied and increased by constant pumping and revetting of the sides of trenches with a skin of empty sandbags held in place by wire netting, in default of which the rain would simply wash the sides of the trench away. The roads, as I have said before, go all to pieces. A hole eighteen inches deep and two yards wide is a common thing to find in the centre of a main highway, despite all the patching and rolling that goes on even by night as well as day.

As a rule, the weather does not get really bad in the Balkans until after Christmas, but the first three months of the year are most unpleasant and of a nature to put all operations of any importance out of the question.