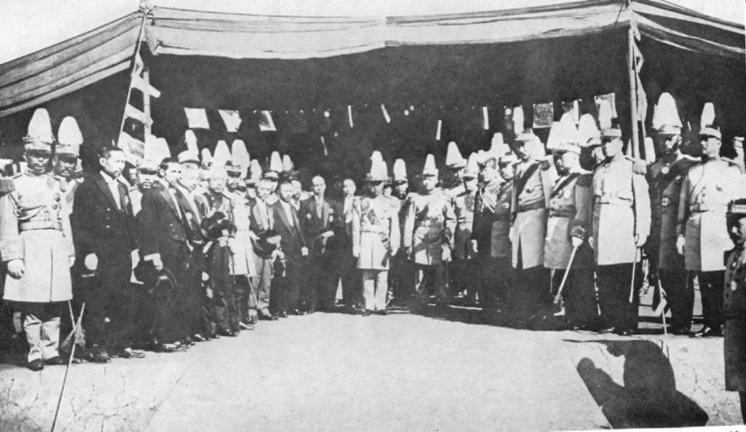

Fig. 5. Feng Kwo-chang. Third President of the Republic, and Staff, in Peking, Oct 10, 1917

W. Reginald Wheeler

China and the World War

.

CHAPTER V

CHINA'S DECLARATION OF WAR AGAINST GERMANY AND AUSTRIA

On March 14, 1917, China severed diplomatic relations with Germany; exactly five months later, on August 14th, she declared war. The strain of reaching this final decision shook the Republic to its foundations, temporarily causing a complete breakdown of the Central Government, and indirectly making possible the brief restoration of the Manchus which took place in July. But eventually the Chinese ship-of-state righted itself and emerged on the broad seas of world-relationships as a recognized member of the league of the Allies.

The breaking off of relations with Germany brought to light the state of discord which had existed for some time between the Premier, Tuan Chi-jui, and the President, Li Yuan-hung. The former was a military leader and had been trained in the Manchu type of government. The latter was a real republican in spirit and had insisted that every act of the State be carried out according to the existing Constitution. The Premier desired to break off relations without consulting Parliament; the President insisted on the latter step, and after Tuan had threatened to resign, and had actually left the capital for Tientsin, the President persuaded him to return and to present the question to Parliament. This was done with the result already indicated.

Having taken two steps, the next move was to declare war. Here, however, appeared many difficulties. It is hard for a foreigner to judge Chinese public opinion, but after a trip through the coast cities into the interior, the following arguments for and against the declaration seemed to the writer to be involved.(12)

The reasons in favour of the declaration seemed to be four in number. First, the intelligent Chinese sympathized deeply with the cause of the Allies, especially in their championing the rights of small or weak nations, with the protection of such countries from aggression and the assurance to them of the right to work out their own destinies unafraid. This formula seemed to fit the facts of China's relationships in the Orient. She was trying to build up a republic; she had made many costly mistakes; but ultimate success seemed possible if she could be protected from attack by predatory powers. The Allies promised such protection to all such weak nations, and China could not but be in sympathy with their aims.

Secondly, China desired a place in the Peace Conference which would be held at the close of the war. There were many questions affecting its own territory and rights which would come up then, and China desired a voice in their settlement. The German rights in Shantung which seemed likely to fall to Japan; the subject of the Twenty-one Demands; the future of the Boxer Indemnity; the principle of ex-territoriality and foreign control of some of China's sovereign rights; all these and many other matters might be reviewed at this future conference. China wished to be heard there, and the best hope of securing a place at the Council Table seemed to lie in joining the Allies.

China has always been influenced by the United States; she trusts American friendship; and is willing to follow its leadership. The United States is the only great nation which has never deprived China of any of its territorial possessions; by the return of the unused portion of the Boxer Indemnity, she had impressed China with the genuineness of her friendship; through the Chinese students who have gone to America, the best traditions of the Republic had been brought to China. The Chinese Republic was striving after American ideals of freedom and democracy, and in shaping its international policy it was ready to listen to America's voice. Moreover, the American Minister at Peking, Dr. Paul S. Reinsch, had a wide influence among Chinese officials.(13) Thus, when the United States severed relations with Germany, China at once followed suit; when America declared war in April, the Chinese leaders were ready to do the same, and were delayed only by the internal situation which at once arose.

In the fourth place, the joining of the Allies seemed to promise to the party in power which made this decision, considerable advantages in strength and prestige, and the Chinese politicians were not slow to grasp this fact.

An example of the reasoning of those in favour of a declaration of war was that of the scholar Liang Chi-chao, whose services to the Republic have already been mentioned.

"The peace of the Far East was broken by the occupation of Kiaochow by Germany. This event marked the first step of the German disregard for international law. In the interests of humanity and for the sake of what China has passed through, she should rise and punish such a country, that dared to disregard international law. Such a reason for war is certainly beyond criticism.

. . . " Some say that China should not declare war on Germany until we have come to a definite understanding with the Entente Allies respecting certain terms. This is indeed a wrong conception of things. We declare war because we want to fight for humanity, international law and against a national enemy. It is not because we are partial towards the Entente or against Germany or Austria. International relations are not commercial connexions. Why then should we talk about exchange of privileges and rights? As to the revision of customs tariff, it has been our aspiration for more than ten years and a foremost diplomatic question, for which we have been looking for a suitable opportunity to negotiate with the foreign Powers. It is our view that the opportunity has come because foreign Powers are now on very friendly terms with China. It is distinctly a separate thing from the declaration of war. Let no one try to confuse the two.

. . . " In conclusion I wish to say that whenever a policy is adopted we should carry out the complete scheme. If we should hesitate in the middle and become afraid to go ahead we will soon find ourselves in an embarrassing position. The Government and Parliament should therefore stir up courage and boldly make the decision and take the step."

Opposed to the four general reasons given for participation on the side of the Allies, there were five groups of arguments. The first was the difficulty China had in reconciling the professed aims of the Allies with its experienced relations with Japan. Rightly or wrongly, for the past twenty years, China had stood in mortal terror of its island neighbour. It had lost to it Formosa, Korea, portions of Manchuria and Mongolia, Tsingtao and the German holdings in Shantung, and had just recently gone through the humiliation of the Twenty-one Demands. The Allied program in Europe called for reparation and restitution for international injuries; China could not understand why this principle should not be accepted in Asia, especially as it applied to its relations with Japan. The existing Terauchi government professed to be friendly to China, but the Chinese felt that such a friendly attitude could not now be reciprocated, unless reparation were made for the acts of the past. Thus fear of Japan was an undoubted obstacle to China's believing in the Allied aims as applied to the Orient.

In the second place, the Chinese were still afraid of Germany's power and feared the eventual vengeance of its army if China should dare to declare war. German propaganda had skilfully magnified German successes and Allied losses, and in 1917 the average Chinese believed firmly that Germany would win the war. German officers had trained the Chinese army, as they had the Japanese troops, and they stood for military efficiency and power in the eyes of the Chinese.

Furthermore, Germany, despite its harsh treatment in the past, had energetically and cleverly conducted a campaign to win the favour of the Chinese, sending out consuls and diplomatic officials who were scholars in Chinese literature and philosophy with sufficient funds to entertain Chinese officials as they like to be entertained; on the other hand, the Allies had at various times, perhaps unconsciously, offended the Chinese. The opium trade,---carried on largely by citizens of the Allied countries in the foreign settlements,--- which followed the British "opium war" and the seizure of Hong-kong and other territory; the recent Lao-hsi-kai affair in Tientsin, where French officials attempted to appropriate property which the Chinese thought was theirs; the advice of the American adviser, Dr. Goodnow, to return to the Monarchy; the ineffectual enforcement of the Open Door; all these facts tended to produce a pessimism in the minds of the Chinese regarding idealistic words which seemed to be unbacked by deeds. This pessimism was shared by many of the younger foreign educated leaders in regard to the favourable outcome of the Conference at the close of the war; to many it seemed immaterial whether or not China should have a voice in the council.

In the fourth place, the younger progressive element of the republic feared the new power which would accrue to the more conservative party in control of the government at the time of the war-decision. They were afraid that the new power would be used as Yuan Shih-kai had used the financial support of the five Powers in 1913, to restrict and harm the more democratic tendencies of the Republic.

Other factors were a realization that their own military power was slight, and a fear of "losing face" by comparison with the Allies; the fear that food prices would increase; the devotion to peace, which is deep rooted in the nation; and finally the policy of "proud isolation," which until recent years had marked all China's relations with other nations. It was a long step for a people ruled for centuries by an alien dynasty to attempt republican self-government: it was an almost incredible act for China as a whole to grasp the existing world situation and to take its proper place in relation to it.

An illustration of this general opposition against the declaration of war was the statement of Kang Yu-wei, formerly a fellow-reformer of Liang Chichao. In it he said in part:

. . . "The breach between the United States and Germany is no concern of ours. But the Government suddenly severed diplomatic relations with Germany and is now contemplating entry into the war. This is to advance beyond the action of the United States which continues to observe neutrality. And if we analyse the public opinion of the country, we find that all peoples --- high and low, well-informed and ignorant---betray great alarm when informed of the rupture and the proposal to declare war on Germany, fearing that such development may cause grave peril to the country.

. . . "Which side will win the war? I shall not attempt to predict here. But it is undoubted that all the arms of Europe ---and, the industrial and financial strength of the United States and Japan --- have proved unavailing against Germany. On the other hand, France has lost her Northern provinces; and Belgium, Serbia and Rumania are blotted off the map. Should Germany be victorious, the whole of Europe --- not to speak of a weak country like China --- would be in great peril of extinction. Should she be defeated, Germany still can --- after the conclusion of peace --- send a fleet to war against us. And as the Powers will be afraid of a second world-war, who will come to our aid? Have we not seen the example of Korea? There is no such thing as an army of righteousness which will come to the assistance of weak nations. I cannot bear to think of hearing the angry voice of German guns along our coasts!"(14)

Such was the situation in general, following the severance of diplomatic relations with Germany. Public opinion seemed about evenly divided, but nevertheless it seemed fairly certain that the "third step" of the declaration of war against Germany would be taken in due time. Thus, on April 16, following the detention of the Chinese Minister at Berlin, the Peking Gazette, the most influential of the papers published by the Chinese, requested an early decision. But at this point the Premier thought fit to summon a council of Military Governors and their representatives to hasten the decision of the country, and the ultimate consequences were disastrous.

The conference met April 25. After much arguing and exhorting, the majority of the conference were won over to the view of the Premier. But signs of opposition on the part of the Parliament against the Premier and his supporters began to develop. There was also the feeling that the Premier had promised certain returns from the Allies, such as increase of the Chinese customs duties, and relief from the Boxer indemnity, but that on account of the opposition of Japan, and for other reasons, these returns could not be secured.

On May 1, however, the Cabinet passed the vote for war without asking conditions or returns, and on May 7 the President, through the Cabinet, sent a formal request to Parliament to approve of this declaration. Parliament delayed, and then, on May 10, an attempt was made to force it into a decision by a mob which gathered outside the National Assembly and threatened the members of both houses. There seems to be little doubt that some official of the Government had incited and promised protection to the mob, as it collected at 10 o'clock in the morning and was not dispersed until 11 at night, when the report was circulated that a Japanese journalist had been killed. The Peking Gazette openly accused the Premier of being behind the riot. Telegrams from all parts of the country poured in protesting against this attempted coercing of Parliament; all the Ministers of Tuan's Cabinet resigned, leaving him standing alone.

On May 18, the Peking Gazette, edited by Eugene Chen, a Chinese born and educated in England and a British subject, a brave opponent of Yuan Shih-kai and the monarchical schemes, and a staunch supporter of the republic, published an article entitled "Selling China," in which it accused the Premier of being willing to conclude with the Japanese Government an agreement which much resembled Group V of the Twenty-one Demands of 1915. That night Mr. Chen was arrested, and later, without any fair trial, he was sentenced to four months' imprisonment. The case stirred up much comment, and finally, as a result of the intercession of C. T. Wang and others, on June 4, the President pardoned him.

Meanwhile events were marching swiftly. The contest between militants and democrats was clearcut. Demands were made for Tuan's retirement from the Premiership; his military friends on the other hand urged his remaining in office. On May 19, the decision was reached in Parliament that there was a majority for war, but that the question would not be decided while Tuan was Premier. The Military Governors left on May 21 amid much speculation and some fear as to their future action. Before going they sent a petition to the President, indirectly attacking Parliament, by criticizing the Constitution which it had practically finished and asking that Parliament be dissolved if the Constitution were not corrected. The three points to which they objected were:

"1. When the House of Representatives passes a vote of lack of confidence in the Cabinet Ministers, the President shall either dismiss the Cabinet or dissolve the House of Representatives, but the said House must not be dissolved without the approval of the Senate. (The French system.)

"2. The President can appoint the Premier without the countersignature of the Cabinet Ministers.

"3. Any resolution passed by both houses shall have the same force as law."

Obviously these three points gave more power to the President and to Parliament than an autocratic Premier and his supporters would desire. The answer to this petition was an increased demand for the retirement of Tuan and the formation of a new Cabinet. The Premier refusing to resign on May 23, the President dismissed him from office. Wu Ting-fang was appointed acting Premier, and there was a feeling of relief. Li Ching-hsi, nephew of Li Hung-chang, was nominated on May 25 for Premier, and on May 28 his nomination was passed by the House of Representatives, and next day by the Senate. On May 30, C. T. Wang, Chairman of the Committee for Writing the Permanent Constitution, published a statement saying that the second reading was practically finished and reviewing the chief points of interest in the new document ready for promulgation.

The Chinese ship of state seemed to have weathered another of its many storms. But suddenly rumour came from Anhwei that General Ni Shih-chung had declared independence, and that he was backed by Chang Hsun, an unlettered "war lord" of Anhwei, and by most of the other Northern Generals and Governors, who, as Putnam Weale put it, looked upon Parliament and any Constitution it might work out as "damnable Western nonsense, the real, essential, vital, decisive instrument of Government in their eyes being not even a responsible Cabinet, but a camarilla behind that Cabinet which would typify and resume all those older forces in the country belonging to the empire and essentially militaristic and dictatorial in their character." This declaration of revolt was received without approval by the people of the country. The writer talked with men from many sections of the country, and they all agreed that the Military Governors had no definite ideal or purpose, except their own glory and power.

Fig. 5. Feng Kwo-chang. Third President

of the Republic, and Staff, in Peking, Oct 10, 1917

All waited for the President to speak. His answer to this defiance came in no uncertain tones and was received by patriots with enthusiasm. Some of the more important passages in his message were:

"It is a great surprise to me that high provincial officials could have been misled by such rumours into taking arbitrary steps without considering the correctness or otherwise of the same. . . . You accuse the Cabinet of violating law, yet, with the assistance of a military force, you endeavour to disobey the orders of the Government. The only goal such acts can lead to is partition of the country like the five Chi and making the country a protectorate like Korea; in which case both restoration of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic will be an idle dream. You may not care for the black records that will be written against you in history, but you ought certainly to realize your own fate. . . .

"I am an old man. Like the beanstalk under the leaf I have always been watching for any possibility of not seeing and understanding aright. Yea, I walk day and night as if treading on thin ice. I welcome all for giving me advice and even admonition. If it will benefit the country, I am ready to apologize.

"But if it be your aim to shake the foundations of the country and provoke internal war, I declare that I am not afraid to die for the country. I have passed through the fire of trial and have exhausted my strength and energy from the beginning to the end for the republic. I have nothing to be ashamed of. I will under no circumstance watch my country sink into perdition, still less subject myself to become a slave to another race.

"Of such acts I wash my hands in front of all the elders of the country. These are sincere words from my true heart and will be carried out into deeds.

"LI YUAN-HUNG."

May 31, 1917.

Following the declaration of independence of the northern provinces, most of the southern ones declared their opposition to this stand. They were led by Yunnan, Kweichow, Kwantung, and Kwangsi, who originally opposed the monarchical movement of Yuan Shih-kai in 1916. Some of the loyal Generals' telegrams were hotly worded. From Tang Chi-yao, Governor of Yunnan:

"Chi-yao is unpolished in thoughts and ignorant of the ways of partisanship or factionism. All he cares and knows about is to protect the republic and be loyal to it. If any one should be daring enough to endanger the Chief Executive or Parliament, I vow I shall not live with him under the same sky. I shall mount my steed the moment order is received from the President to do so."

From a General in Kwantung:

"The reason why the rebels have risen against the Government is that they are fighting for their own posts and for money. That is why their views are so divergent and their acts so ill-balanced. It is hoped the President will be firm to the very last and give no ear either to threat or inducement. This is the time for us to sweep away the remnants of the monarchist curse and reform the administration. With my head leaning against the spear I wait for the order to strike and I will not hesitate even if I should return to my native place a corpse wrapped up in horse-skin! "

The military party nevertheless met at Tientsin and elected Hsu Shih-chang, Generalissimo. But soon signs of dissension appeared among them. On June 7 was made public a friendly warning from America. The American Minister, Dr. Reinsch, transmitted the following message to Dr. Wu Ting-fang, the Minister of Foreign Affairs:

"The Government of the United States learns with the most profound regret of the dissension in China and desires to express the most sincere desire that tranquillity and political co-ordination may be forthwith re-established.

"The entry of China into war with Germany --- or the continuance of the status quo of her relations with that Government --- are matters of secondary consideration.

"The principal necessity for China is to resume and continue her political entity, to proceed along the road of national development on which she has made such marked progress.

"With the form of government in China, or the personnel which administers that government, the United States has an interest only in so far as its friendship impels it to be. of service to China. But in the maintenance by China of one central united and alone responsible government, the United States is deeply interested, and now expresses the very sincere hope that China, in her own interest and in that of the world, will immediately set aside her factional political disputes, and that all parties and persons will work for the re-establishment of a co-ordinate government and the assumption of that place among the powers of the world to which China is so justly entitled, but the full attainment of which is impossible in the midst of internal discord."

This note was welcomed by Chinese as a pledge to support the Central Government. It aroused some resentment in Japan because the Japanese had not been first consulted. On June 9 an ultimatum was sent from Tientsin either by Chang Hsun or by Li Ching-hsi, threatening to attack Peking if Parliament was not dissolved. The President was isolated and members of Parliament and other democrats could not reach him. Rumour reported that he was about to give in and dissolve Parliament. The British adviser to the Chinese Government advised him not to do so. The Japanese adviser gave the opposite counsel. Wu Ting-fang, Acting Premier, refused to sign the mandate. Finally, on June 12, the mandate was issued, countersigned by General Chiang Chao-tsung, commander of the Peking gendarmerie. The next day an explanation was made by President Li in which he admitted he was forced to issue a mandate against his will, but that he did it to save Peking and the country from war and destruction. He declared he would resign as soon as opportunity came.

On June 15, Chang Hsun arrived in Peking with Li Ching-hsi. Eight of the provinces that week cancelled their independence, stating that their desire for the dissolution of Parliament had been satisfied. The members of the Parliament made their way, many of them in disguise, to Shanghai and there held meetings and sent out manifestoes. Affairs were apparently at a standstill with the country thus divided when the great coup d'Ètat was carried out by Chang Hsun. Affairs thereupon moved swiftly.

On June 30, Kang Yu-wei, a well-known advocate of the monarchy, arrived in Peking. He had travelled incognito from Shanghai. His first visit was to Chang Hsun. On July 1 at 4 A.M. Chang Hsun and his suite called on the Manchu boy-Emperor(15) and informed him of his restoration, and seated him on the throne. President Li Yuan-hung was requested to resign, but refused. He was then practically held prisoner. Numerous imperial edicts were issued, countersigned by "Chang Hsun, member of the Privy Council."

On July 3, Feng Kuo-chang repudiated any connection with the restoration, his name having appeared in the edicts as one of the petitioners. The Military Governor of Canton issued proclamations that the Cantonese would fight to maintain the republic. Many similar messages were sent by other provinces.

Japanese troops proceeded to the Forbidden City, took President Li Yuan-hung out of the custody of Chang Hsun's men and escorted him to the Japanese Legation. On July 4 the President issued a pledge to support the republic. On July 5 hostilities broke out at Lang Fang on the Peking-Tientsin railway. The diplomatic body notified the Peking authorities that the Protocol of 1901 providing for open railway communication between Shanhaikwan and Peking must be observed. On the same date trains out of Peking were packed to overflowing with Chinese fleeing to Tientsin.

By this time the entire country, with the exception of three provinces, had declared its opposition to the Manchu movement. Tuan Chi-jui came out of his retirement, offering to take command of the Republican army. Liang Chi-chao, who was such a force against Yuan Shih-kai, denounced the whole movement.

The Republican troops advanced upon Peking, and on July 7, American, Japanese, and British soldiers arrived at the capital. An airplane later dropped a bomb over Fengtai station and wrecked the shed. Chang Hsun's troops at Paoma Chang retired inside the capital without fighting and concentrated at the Temple of Heaven. Another airplane flew over the Forbidden City and dropped bombs. Chang Hsun, on July 8, resigned, but the abdication of the Emperor was not published, his protector holding out for favourable terms.

Vice-President Feng Kuo-chang assumed the office of Acting President at Nanking, which was declared the capital of the Provincial Government. Dr. Wu Ting-fang arrived in Shanghai with the seal of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Several Ministers of the Manchu Cabinet on this day were captured while attempting to escape. Chang Hsun refusing to surrender and 50,000 Republican troops having surrounded Peking, on July 12, at four in the morning., the attack was begun in earnest. Several foreigners were wounded; fire broke out in the Forbidden City; Chang-Hsun took refuge in the Dutch Legation, and the Republican flag was raised over the Forbidden City.

On July 14, Tuan Chi-jui arrived in Peking. It is rather interesting to note that on July 4 practically the entire country voiced its "declaration of independence" from this Manchu Government; on July 14, the victorious Republican generals entered the capital. This opposition and this victory of the Chinese Republicans took place on the Independence Days of the American and the French Republics; the coincidences seemed both significant and symbolic. On July 15 Tuan Chi-jui assumed the office of Premier, though the southern provinces showed opposition to him. On July 17 President Li, in a telegram to the provinces, refused to resume office, and Acting President Feng Kuo-chang expressed his willingness to succeed Li Yuan-hung.

The attitude of liberal Chinese during this crisis was revealed by two speeches made by former officials, July 13, in Shanghai. Dr. Wu Ting-fang, formerly Minister to the United States, who had stood so firmly against any unconstitutional action on the part of the monarchists, said:

"The war in Europe is being fought to put an end to Prussian militarism; and I want the Americans here to understand that China's present troubles are due to exactly the same causes. We are engaged in a struggle between democracy and militarism. Between 55 and 60 per cent. of the taxes of China are now going to support militarism in China. This must be changed, but the change must be gradual. I ask Americans to be patient and give China a chance. Democracy will triumph. Please be patient with us. Study China and try to see us from our own point of view instead of your own.

"I hope to see the day when the Stars and Stripes and fire-coloured flag of China will be intertwined in an everlasting friendship. These nations believe in universal brotherhood; in the rights of the people of small nations to manage their own affairs, as outlined by the great American President in his war declaration. I make this statement with hostility to no nation."

Hon. C. T. Wang, Vice-President of the Chinese Senate, spoke in the same vein:

"The real issues are: Shall there be government by law or by force? Shall the will of the people as expressed through the Assembly prevail, or that of a privileged few? Shall the military forces of the nation be used to uphold the country, or to uphold certain individual generals? Upon these issues the country and the free and democratic nations of the West should be called upon to pass judgment.

"With the strongly ingrained love for democracy and the firm belief in the necessity of subordinating military authority under the civil, in the character of our people, we do not hesitate for a minute to affirm that in China, just as it is in free and democratic nations of the world, constitutionalism shall prevail over militarism. We, like the Entente Allies, have time on our side. We shall have to make the same sacrifices for the final victory of constitutionalism and democracy as they are making in their titanic struggle on the battlefields of Europe. Let us resolve that we will."

During this period of intense disturbance there was a general feeling among foreigners that assistance should be given to the democratic elements in China in their attempt to defend the Republic. Especially was American sympathy aroused, and various statements were made by journalists and others, that since America was assisting the newest Asiatic Republic of Russia in its struggle against autocracy, it should also extend its support to the Republicans who were fighting the same battle in China. Thus Mr. T. F. Millard, a well-known journalist and authority on matters in the Far East, on July 21 voiced his idea of America's duty:

"Yes, it is very inconvenient for democracy, at the time when the issue of a world-war is narrowing down to a test of the fate of democracy, to have two great nations like Russia and China trying republicanism for the first time, and under precarious conditions; for the difficulties of Russia approximate the internal difficulties of China with republicanism. But just because the local and general conditions are rather unfavourable, and further because of the linking of these experiments with the cause of democracy throughout the world by reason of the war, it becomes virtually impossible for the United States to remain a mere spectator of the course of events in Russia and China. Action to hearten, encourage, and support Russia already has been taken by the United States Government. Action to hearten, encourage, and support China in her effort to maintain a republic ought to be devised and undertaken without delay."

But the Republicans regained control of the government without foreign assistance, and on August 1, Feng Kwo-chang succeeded Li Yuan-hung as President. Before the new President had been in office a week the subject of the declaration of war was again brought up. There was little opposition now to the decision, and on August 14th, 1917, the Chinese Republic formally declared war on the German and Austrian empires.