By early 1915, the fighting on the Western Front had stalemated into static trench

warfare. The death toll had reached such epic proportions that neither the British,

French or Germans could keep up the insane tactics of mass charges by their troops

across no-mans land only to be slaughtered in vast numbers by machine gun fire,

artillery barrages or die entangled in barbed wire or drown in mud. Static warfare

was not how the generals of the time wanted the war conducted and Allied General

Headquarters in France began demanding a solution to the trench warfare be found.

An accomplished writer for the British Army, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Swinton, observed first hand the early battles and reported to his superiors in his opinion, a petrol tractor on the caterpillar principal, with hardened steel plates, would be able to counter the effects of the machine gunner. His proposal the British Army build such a vehicle was rejected by General Sir John French and his scientific advisers. Fortunately Swinton’s report had been read by Winston Churchill, the First Sea Lord who had a little more imagination than his colleagues. He liked the idea and set up in February 1915, a Landship Committee to look into the possibility of developing the new war machine Swinton had proposed. The committee commissioned Lieutenant W.E.Wilson of the Naval Air Service and William Tritton of William Foster and Company of Lincoln to construct a small landship. The work was carried out in great secrecy and the new war machine was code-named ‘water tank’ based on the size and shape of the fresh water tanks on the battle field. The name was to be eventually shortened to ‘tank’ by the troops.

The first prototype was demonstrated to the Landship Committee on September 11 1915, but its performance was disappointing as it couldn’t cross broad trenches. Wilson and Tritton immediately went back to work to design a better model. It was Wilson who came up with the idea of taking the tracks right round a body of rhomboid shape, pointed at the top and sloping down at the back. All work was concentrated on Wilson’s design. After much trial and error, the first crude British tanks were shipped to the Western front and spearheaded the attack on the Somme on 15 September 1916. Historical records vary but of the approximately 47 tanks that were brought up for the attack, only 11 actually went into battle. The long hoped for decisive victory was not achieved despite the surprise and terror the new weapon caused the Germans. The tanks were underpowered, unreliable and too few in number. It is only conjecture, but the outcome of that particular battle and many more in the future may have been different if the ideas of an Australian inventor had been used when offered.

Lancelot Eldin DeMole was born in Kent-town South Australia on the 13 March 1880 and by 1908 was a draughtsman and inventor working on surveying and mining projects in several Australian states. One of his early inventions was an automatic telephone system designed three years before a similar type was introduced into the United States. A typical example of the failure to exploit a potentially good idea was that the Australian Postal Department declined to even test it. DeMole, while working in the very rugged countryside of Western Australia had the idea for a chain rail system of traction for use in heavy haulage. This idea led him to work on a design for a chain rail armoured vehicle. He sent his sketches to the British War Office in 1912.

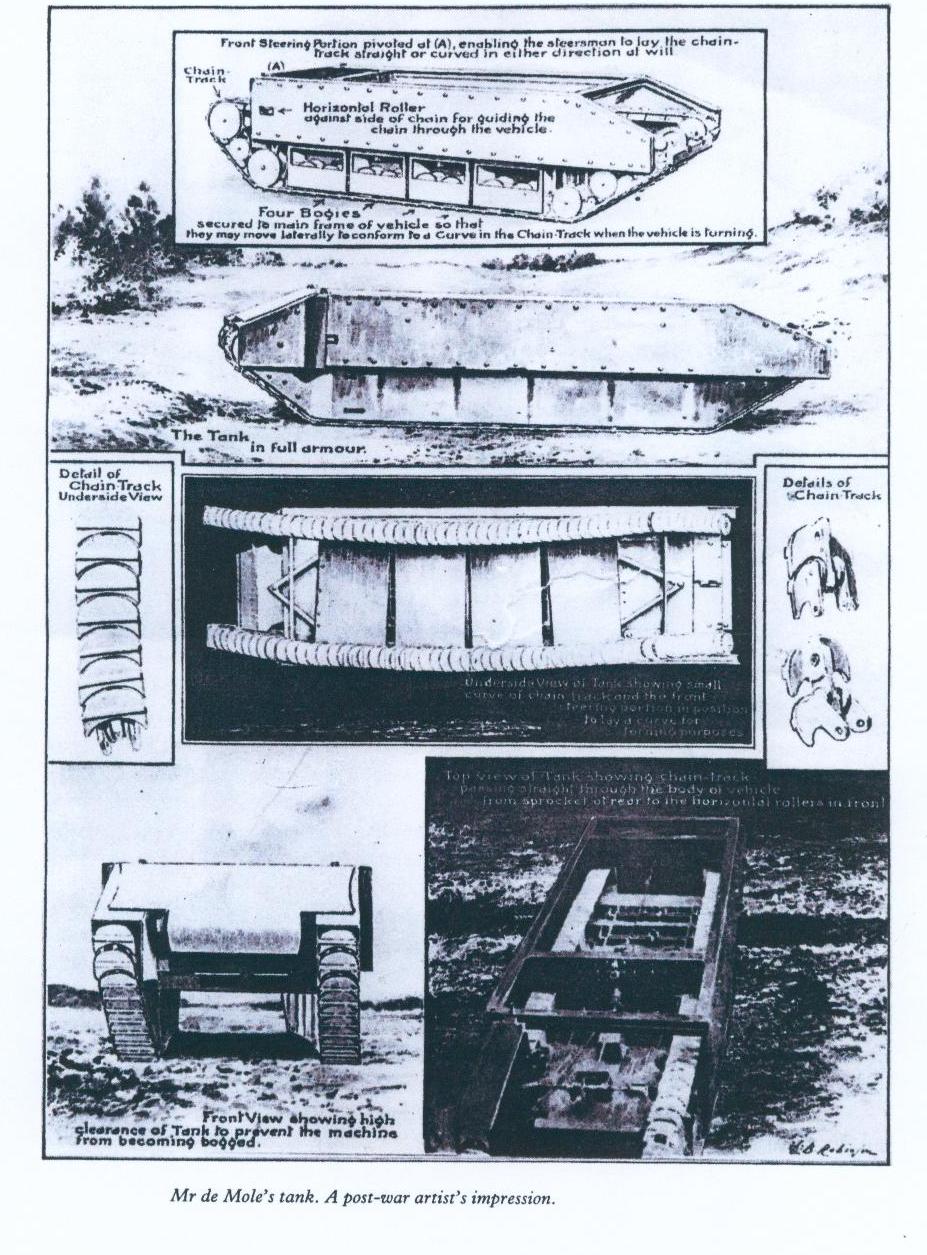

The principal operation of his vehicle was that his machine could be steered to the right or left when proceeding forwards by altering the direction that the chain rail could be laid. By screwing the front portions to one side or the other side or steered when proceeding backwards by pressing the bogie nearest the rear end of the vehicle to one side by means of a screw gear or a hydraulic ram controlled by the steersman. This causes the body of the vehicle to be thrown to the right or left as required so that as the machine proceeds, the links of the chain rail will be laid to the right or left of the line that the vehicle has been proceeding on. This forms a curve which as the vehicle proceeds, will alter the direction of travel. Perhaps it was all too complicated for the British War Office as they returned some of his sketches in 1913 with a letter rejecting his idea and the comment that they were no longer experimenting with chain rails.

DeMoles friends urged him to try and sell his idea to the German consul in Western Australia but he declined with the comment that they may one day be an enemy. The outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 proved him right With Britain at war, Australia, as part of the British Commonwealth also declared war on Germany. DeMole, like so many of his fellow countrymen, answered the call to war with patriotic fervour. His initial attempt to enlist in the Australian Imperial Forces was unsuccessful as the Army rejected him as too tall and delicate.

As the war progressed, the Land ship Committee and the development of the tank were of course unknown to DeMole. The new secret weapon only became common knowledge after the Somme battle. Personal papers and official documents differ

slightly as to the exact date, but it is generally accepted that DeMole re-submitted his plans based on the original ones from 1912 to the British Munitions Inventions Office around July or August 1915 or possibly in early 1916. In any case, the British authorities failed to pass on his design to the Landship committee. One can only speculate why the plans were not made available to the people who were working on the tank. It’s possible the Munitions Inventions Office knew nothing of the Landship Committee because of great secrecy that surrounded what they were doing or perhaps there was some form of inter-departmental rivalry. What ever the reason, an opportunity to explore a new idea was wasted.

DeMole did receive a letter from the Munitions Inventions Office suggesting that a working model must be provided to have any chance of consideration. Not being the type to give up easily, DeMole tried to get the local South Australian Inventions Board interested in his idea. The official in charge could not understand the plans. The idea was rejected with the weak excuse that there might be a hole and the vehicle might fall in it. DeMole was thinking of a fleet of 500-1000 armoured vehicles with mounted guns that could be used to attack the enemy in overwhelming force but the official lacked imagination and could only think in terms of one. It was only when the bitter fighting in the Somme was over and the secret of the tank became common knowledge, did DeMole realise his design was superior and had been completely ignored by the British authorities.

In order to try and enlist again, he went on a special diet to improve his health and was finally allowed to join in 1917 as a private in the 25th Re-enforcements, 10th Battalion, Australian Imperial Forces. With financial backing from a friend, Lieutenant Harold Boyce, [later to become Sir Harold Boyce and Lord Mayor of London] DeMole had a metal model of one eighth scale constructed by the mechanical and electrical engineering firm of Williams and Benwell in Melbourne. They described the model as being remarkable from an engineering point of view. Lieutenant Boyce managed to get Private DeMole assigned to him and they departed from Melbourne on the troopship A60 [Blue Funnel liner Aeneas] via the Suez Canal. Locked in the ships orderly room under constant guard was the model tank. As soon as they arrived in the English port of Plymouth, DeMole managed to get leave to take his model to the Munitions Inventions Office. By now it was January 1918.

His model passed the first test and he was asked to demonstrate it to a second committee. Just when it seemed he was actually getting somewhere, DeMole became sick and was unable to follow up with the second demonstration. He returned in March to the Munitions Inventions Office only to find his model had been left in a basement and the letter from the first committee recommending his model to the Tank Board had not been passed on to the second committee. Before he could arrange a second demonstration the Germans launched their spring offensive at 9.40 am on March 21. After a five hour bombardment, the German army struck a massive blow against the weak divisions of the British Third and Fifth Armies. DeMole was called back to active duty with the 10th Battalion and fought at Merris, Meteren and Villers-Bretonneux. He remained in France until the armistice then returned to London to be demobilised. It was here that he heard about a Royal Commission being established to reward inventors for their contribution to the war effort. With regards to the area of tank development, DeMole, along with a few others lodged his claim.

In November 1919, the Royal commission handed down their findings. The credit for designing the tank actually used went to Wilson and Tritton and they were jointly awarded 15,000 pounds. As to Lancelot Eldin DeMole’s claim, the commissioners considered he was entitled to the greatest credit for having made and reduced to practical shape as far back as 1912, a brilliant invention which anticipated, and in some respects, surpassed that which was actually put into use in the year 1916. The commissioners went on to say that it was the claimant’s misfortune and not his fault that his invention was in advance of its time and failed to be appreciated and was put aside because the occasion for its use had not yet arisen. They regretted they were not able to recommend any award to him. They explained that a claimant must show casual connection between the making of his invention and the use of any similar invention by the Government. DeMole was however, awarded 965 pounds for out of pocket expenses by the British Government.

DeMole’s tank was more manoeuvrable than early British variety. It incorporated a piece of mechanism that simplified the handling of the tank and enabled it to be steered in a comparatively sharp turn. It also had climbing face at both the front and back which enabled the tank to back out of trouble, which the early British tanks could not do. DeMole’s invention looked good on paper and mapped out what Wilson and Tritton had to work out the hard way. His plans did not include an engine or any form of armaments as he was convinced those things were better left up to the experts in those fields. Unfortunately for him and history, his plans were never built and tested with a full scale vehicle so it is only speculation how much if any, his contribution would have had on the design and development of the early tanks. This lack of a test vehicle may explain why many historians both past and present tend focus on Tritton and Wilson’s achievement and ignore DeMole altogether either out of ignorance or being too selective in their writings about the early development of the tank. As a result of this deplorable treatment, his name and what he tried to achieve has been all but forgotten even in his own country.

After the war, the newly established Australian War Memorial in the Australian

capital of Canberra sent DeMole a letter asking him if he would be prepared to

donate his model to the museum. The displays would include trophies and relics

captured or acquired by Australian troops and would also include a tank section

and the model as a tribute to the inventive genius of Australians. On 28 July 1921,

a grateful Australian Government placed him on the New Years Honour list and

awarded him with the C.B.E.

After a long illness, Lancelot Eldin DeMole died in 1950. His model is currently in

the Australian War Memorials Treloar Centre for conservation.