In

Memoriam

March 8, 1923, Berlin – September 1, 2008, Los Altos, California

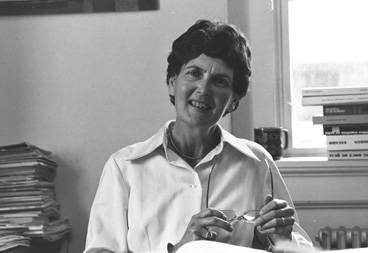

Agnes F. Peterson, who served as Curator of the Central and Western European Collections of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University for 41 years, died in Los Altos on September 1, 2008. She had been in ill health for several months. The cause of death was heart failure. In accordance with her wishes, there was a small, private burial service. She is survived by her husband of 53 years, Professor Louis John Peterson.

Agnes Peterson was first hired by the Hoover Institution Library April 16, 1952, after having received her undergraduate degree in history at the University of Toronto and receiving her master’s degree, also in history, from Radcliffe. She had previously worked with the documentary film program of the National Film Board of Canada and the California Historical Society in San Francisco, where she was a research assistant. Agnes was a loyal colleague to Hoover Library founding co-director Ralph Lutz, a Stanford faculty member, who specialized in German history. Her work with Lutz and her collegial friendship with his son-in-law, history professor Charles Burdick, ensured a chain of continuity with the very origins of the Hoover Institution.

Softly voiced, rigorously accurate, unfailingly polite, and intellectually curious, Agnes found her forte as West European curator, first de facto and then officially in 1958, a position she held until she retired in 1993. She ordered tens of thousands of books for quite literally thousands of scholars, often expediting processing to ensure that a visiting researcher would receive the very latest publications. She facilitated the acquisition of some of the most valuable archival collections at Hoover, such as the Louis Loucheur papers, additional Rosa Luxemburg materials, Himmler’s early diaries, the Karl B. Frank papers, oral histories with European public figures conducted by Keith Middlemas, extensive documents and graphic material from Paris 1968, and videos and posters relating to German reunification. For decades she managed the Library’s depository role for the publications of the emerging European Community. The list of collections established under her tutelage is long.

Many milestones marked her career. In 1980, she was awarded the Order of Leopold II by Belgium. In recognition of her research and writing, she was appointed Hoover Institution research fellow in 1986. In 1990, she received the Distinguished Service Award of the Stanford University Library Council.

While at Hoover, together with Grete Heinz, Agnes compiled a guide to the content of 146 reels of microfilm containing Nazi party documents: NSDAP Hauptarchiv: A Guide to the Hoover Institution Microfilm Collection. She participated in organizing the filming of the documents. She also wrote several definitive bibliographical works and published guides to the Hoover Library’s collections. Again, with Grete Heinz, she compiled two works on the French Fifth Republic. Her work with historian Bradley F. Smith on Heinrich Himmler appeared in 1974. In 1980 she compiled the first guide to the Holocaust research materials in the Library and Archives. She was recognized as a leading expert on the work of the German communist heroine Rosa Luxemburg, and wrote several pieces on the life of Luxemburg’s previously little-known assistant, Matilde Jacob, whose papers Agnes traced down like a sleuth. Her carefully written book reviews, published in Library Journal, History: Review of New Books, German Studies Review, Central European History, and on H-Net, were especially esteemed by scholars as an insider’s analysis.

Throughout her decades at the Hoover Library, Agnes Peterson consistently put the research of library patrons ahead of her own work. Generations of historians benefited from her matchless knowledge not only of the Hoover collections but of European history. She would locate new sources and consistently followed through, matching researchers with the most pertinent materials for their topics. Scholars recall trying to stump her about esoteric subjects, only to hear her say, “Let’s see, I think we have just the thing.” In thanks, her name appears in the acknowledgments of countless volumes on modern history. Some of the researchers she helped include Barbara Tuchman while she worked on the Guns of August, William L. Shirer for his work The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, John Toland during his research for Infamy: Pearl Harbor and Its Aftermath; other examples are legion, among them Ambassador George Kennan, Professors Gordon Wright and Gordon Craig (Stanford), and Robert Wohl (UCLA). During the Cold War, she was famous for maintaining cordial ties on both sides of the divide. Even the formidable East German ideologue Kurt Hager was impressed when he read about her collecting work.

Agnes took a special pleasure in assisting talented, young graduate students and watching them develop into accomplished historians. In just one of many examples, while in Munich in 1965, she helped facilitate an archives research visit for a Stanford graduate student, Sybil Halpern Milton, who later went on to serve as senior historian at the U.S. Holocaust Museum. They had met in 1962 when Sybil was a first-year graduate student, and she and Agnes remained lifelong friends and colleagues.

Without fanfare Agnes also helped found several important academic organizations, first by appreciating the value of creative if ephemeral ideas, and then by carefully implementing them through committee work, tireless memo-writing, and board meetings. In 1979 she secured facilities and funding at the Hoover Institution for one of the founding meetings of the German Studies Association. She served as secretary/treasurer of the organization, then known as the Western Association of German Studies. It is now the preeminent professional organization for the study of Germany in the United States. She was equally active in the American Historical Association and, significantly, the Western European Studies section (WESS) of the Association of College and Research Libraries.

As WESS grew into a major organization of European studies specialists, Agnes advised on a series of European conferences where she delivered papers which were later published in the organization's proceedings. WESS members could easily see her and her contemporary Erwin Welsch, the intellectual founders of their group, and still regard her work as the ideal model of a scholar-librarian who anticipates research needs and creates communities of colleagues where mutual influence enhances continued study. The same can be said for her long-time support of the Women's History/Women Historians Reading group, a gathering of Stanford and Northern California historians whose meetings Agnes often hosted.

She served on several leadership or review boards over the years, including the World War II Studies Association, the Conference Group on Central European History, the consultants’ panel of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Stanford Bookstore.

For all of her strong ties with faculty at universities around the world, she had a deep appreciation of the work done by independent scholars. In 1980 she helped found the Institute for Historical Study, which continues to promote the work of unaffiliated historians. In 1987 she assisted a talented, non-academic businessman to launch the Great War Society, an organization she provided with both logistical support and access to resources in the early years. It still thrives.

The 1980s were a time of particularly great activity for Agnes. She initiated and coordinated a series of free public lectures at Stanford, beginning with the 1981 academic year and continuing until her retirement. In this series, entitled Tower Talks, she organized a total of 95 book talks by distinguished scholars and public figures such as Professor Peter Paret, physicist Edward Teller, diplomat Philip Habib, and Trotsky’s grandson Esteban Volkov. Each speaker received a gracious introduction and a follow-up letter from Agnes, who was surely one of the most prodigious thank-you letter writers of modern times. Since the talks on new books were rather formally structured, she simultaneously coordinated a series of free form roundtable discussions for works in progress.

In short, Agnes Peterson documented the transformation that took place in the second half of the twentieth century. In her own words: “When I started working, the second World War was just over, the cold war had begun, and now, when I have stopped working (at least officially), the cold war is over and the whole world has changed. Few people have the chance to get to do what they like to do, in such exciting times, and get paid for it.”(Speech on the occasion of a Festschrift presented to her by the Great War Society, August 18, 1994.)

Few who benefited from her guidance, however, were aware of her distinguished family’s achievements: characteristically, Agnes rarely discussed them. Many of her closest friends did not know that her grandfather, Emil Fischer, received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1902. Despite her family’s deep ties to Germany, Agnes’s father, Hermann Fischer, a biochemist in Berlin, was so disturbed by the growing Nazi menace in the 1930s that he voluntarily relocated the family first to Switzerland and then to Canada in 1937. Before leaving, he took his daughter to the Louvre to see the Greek sculpture “Winged Victory,” and assured her that this represented the real Europe. Hermann Fischer eventually became professor of biochemistry in 1948 at U.C. Berkeley, where he remained until his death in 1960. The Fischer family quietly preserved the best of European culture during self-imposed exile while contributing to American academic life.

Agnes Gertrud Margarete Ilse Fischer Peterson will be remembered especially for her legacy of tolerance, her devotion to history, her European charm and style, and her infinite number of kindnesses to family and friends. Agnes was, as several scholars have pointed out, “an institution within the Institution.”

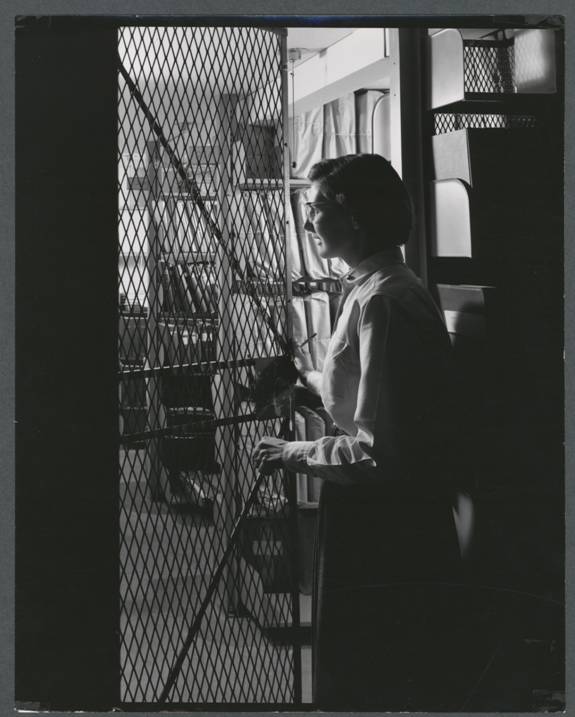

Agnes F. Peterson opening the gate to the rare book vault in Hoover Tower, 1957