|

The old fortress city of Verdun was ringed by strongholds and forts, the largest and most important of these being Fort Douaumont — called by one writer "the most shelled spot on earth." The Germans captured Fort Douaumont in February, 1916; the French finally retook it in October. It is said that retaking Fort Douaumont alone cost the lives of 100,000 Frenchmen.

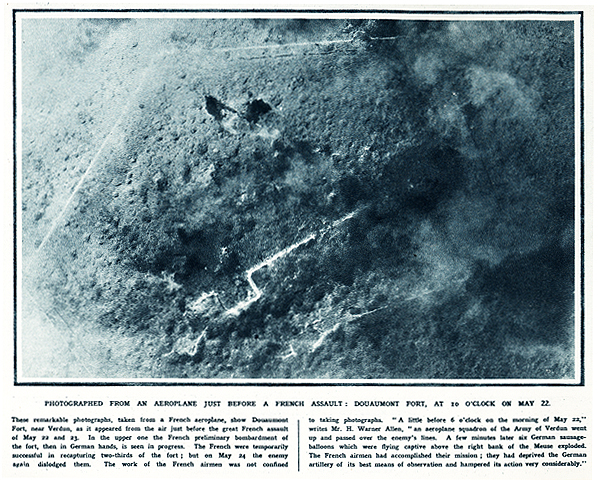

These three photographs from The Illustrated London News of June 24, 1916, show the French counter-attacks on Fort Douaumont on May 22-23, 1916 (click here to read the accompanying text: photo left; photo right; photo below).

"The poignancy [of the dead men walking scene] is strengthened by what is known of the making of the film. The army provided two thousand soldiers for the sequence, most being on eight days leave after four years of fighting. Gance said: ‘These men had come straight from the Front — from Verdun. . . . They played the dead knowing that in all probability they'd be dead themselves before long. Within a few weeks of their return, eighty per cent had been killed.'" (Kelly, 103, 105).

While digging a rail line through the Somme battlefields in 1991-92, to connect with the "Chunnel," the French démineurs ("de-miners") handled an average of five tons of unexploded ordnance per day that had been unearthed during the excavation (throughout France, the démineurs collect some 900 tons of ordnance per year, with 30 tons of that being gas shells). Luckily, no one was killed during the "Chunneling" — although several pieces of construction equipment were totaled — but every year several French démineurs are killed and injured disposing of gas and high-explosive shells, and in 1991 alone, 36 French farmers were killed plowing up unexploded ordnance from the Great War. And in Belgium (especially around the Ypres/Passchendaele area), according to a 1995 newspaper article, it should take yet another 15 years to destroy the stockpiles just of gas shells so far discovered. (For a glimpse at the kind of munitions stockpiles amassed for these battles, click here.) |