|

Forty thousand men Forty thousand strong Forty thousand footsteps Forty thousand men |

.

.

Captain Holderman's Citation

Captain Holderman's CitationMajor Whittlesey, when making his recommendation for the award of the Congressional Medal of Honor to Captain Nelson M. Holderman, whom he designated to command and conduct the defense of the right wing and right flank of the position, had the following to say:

"While in command of Company K, 307th Infantry which company held the right flank of the force consisting of six companies of the 308th Infantry, two platoons of the 306th Machine Gun Battalion and Company K, 307th Infantry, and which force was cut off and surrounded by the enemy for five days and nights in the Forest d'Argonne, France, from October 2nd to October 7th, 1918. Captain Nelson M. Holderman though wounded early in the siege and suffering great pain continued throughout the entire period leading and encouraging the officers and men under his command. He was wounded on the 4th of October but remained in action during all attacks made by the enemy upon the position, personally leading his men, himself remaining exposed to fire of every character. He was again wounded on the 5th of October, but continued personally organizing and directing the defense of the right flank against enemy attacks. During the entire period he personally supervised the care of the wounded exposing himself to shell and machine gunfire that he might help and encourage his men to hold the position. On October 6th, though in a wounded condition he rushed through shell and machine gun fire and carried two wounded men to a place of safety. This officer though wounded, continued to direct the defense of the right flank and on the 7th of October was again wounded but continued in action. On the afternoon of October 7th this officer and one man, with pistols and band grenades alone and single handed, met and dispersed a body of the enemy, killing and wounding most of the party, when they attempted to close in on the right flank while their forces were at the same time making a frontal attack, thus saving two machine gum from capture as well as preventing the envelopment of the right flank. Again on the evening of the 7th of October and during the last attack made by the enemy upon the position, a liquid fire attack was directed or the right flank; though in a wounded and serious condition Captain Holderman remained on his feet, keeping the firing line organized and preventing the envelopment of the right flank. He refused to let his wounds interfere with his duty until after relief was effected. The successful defense of the position was largely due to his courage. He personally led his men out of the position after assistance arrived and before permitting himself to be attended. The courageous optimism and inspiring bravery of this officer encouraged his men to a successful resistance in spite of five days fighting, hunger and exposure."

After Captain Holderman was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, Major Whittlesey wrote him the following letter:

"Dear Captain Holderman:

To my great delight I have just received a notification of the award to you of the Medal of Honor. I am enclosing herewith the carbon copy, although I know the information will have reached you direct.

This is the finest news in the world and I am looking forward with eagerness to passing it on to George McMurtry.

I wish I could be on hand to see you decorated.

Let me hear from you when you can.

With best wishes, as ever,

Sincerely yours,

(Signed) Charles W. Whittlesey."

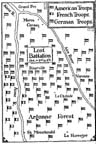

The famous "Pocket" of the Lost Battalion, near Charlevaux Mill, occupied by Whittlesey and his forces from October 2nd to October 8th, 1918.

THAT proper recognition may be given all units represented in the Lost Battalion, I quote herewith; General Robert Alexander's Citation of the "Lost Battalion" published April 15th, 1919 in France, as follows:

"General orders No. 30:

"I desire to publish to the command an official recognition of the valor and extraordinary heroism in action of the officers and enlisted men of the following organizations:

Company A, 308th Infantry

Company B, 308th Infantry

Company C, 308th Infantry

Company E, 308th Infantry

Company G, 308th Infantry

Company H, 308th Infantry

Company K, 307th Infantry

Company C, 306th Machine Gun Battalion

Company D, 306th Machine Gun Battalion

These organizations, or detachments, therefrom, comprised the approximate force of 550 men under command of Major Charles, W. Whittlesey, which was cut off from the remainder of the Seventy-Seventh Division and surrounded by a superior number of the enemy near Charlevaux, in the Forest d'Argonne, from the morning of October 3, 1918, to the night of October 7, 1918. Without food for more than one hundred hours, harassed continuously by machine gun, rifle, trench mortar, and grenade fire, Major Whittlesey's command, with undaunted spirit and magnificent courage, successfully met and repulsed daily violent attacks by the enemy. They held the position which had been reached by supreme efforts, under orders received for an advance, until communication was re-established with friendly troops. When relief finally came, approximately 194 officers and men were able to walk out of the position. Officers and men killed numbered 107.

"On the fourth day a written proposition to surrender received from the Germans was treated with the contempt which it deserved.

"The officers and men of these organizations during these five (5) days of isolation continually gave unquestionable proof of extraordinary heroism and demonstrated the high standard and ideals of the United States Army.

Robert Alexander

Major General, U. S. A. Commanding."

Originally the 77th Division was made of New York men, almost entirely from East Side or the "Melting Pot" of New York This Division was popularly known as "New York's Own," and was organized at Camp Upton, Yaphank, L. I., during the early part of September, 1917.

Before taking over their sector of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the division was strengthened by replacements from the 40rh Division, which was composed of men from all parts of the West, and they were originally stationed at Camp Kearney, California.

The 1st Battalion was led by Major Charles W. Whittlesey, and the 2nd Battalion by Captain George G. McMurtry, with Major Whittlesey in command. Both men were gallant leaders and men that we would follow anywhere. During those trying days the thoughtfulness, courage and leadership displayed by those two men was something wonderful to see. It instilled into the hearts of their men that undying faith of purpose, the courage to go ahead against overwhelming odds, and carried them through six indescribable days and nights of suffering after being completely cut off from their comrades with practically no food or water. They were subsisting on the roots and leaves of trees, at all times under the stress of heavy enemy fire, and fighting off counter-attack after counter-attack with no relief in sight.

The members of this unit were never at any time "Lost," as the name would seem to imply. They were, however, cut off from the balance of their command and were in two separate and distinct "traps," sometimes referred to as first and second "pockets." At the time they were in the second "pocket" Major Whittlesey was in Command, Captain McMurtry second in Command, Captain Holderman was in charge of the right wing or right flank, and Captain Wm. Cullen was in charge of the left wing or flank.

The Argonne Forest was considered impregnable and the Germans felt secure in their possession of this strategic position.

That they never anticipated this stronghold ever being taken from them is mutely proven to this day by the wonder work that some of their sculptors carved in great rocks which still stand silently guarding German graves in that forest. During the four years of their possession they built an elaborate net work of concrete trenches, some theaters and mammoth dug-outs. Some of these dug-outs were equipped as well as our "Twentieth Century" homes, including electric lighting systems and in some isolated cases even bath tubs and pianos. The forest had been used by the Germans during this time as a rest area for their battle-worn troops of other fronts.

In all those four years the Allied Armies, had failed to make a dent on this position., It was a natural stronghold and so dense with underbrush that paths had to be cut through it before travel was possible. The Germans or their prisoners had cut mile upon mile of trails through these woods, and had laid their larger roads with young saplings in order to withstand the travel of their heavier vehicles and dogs of war. These positions were fully covered by machine guns from protected and well camouflaged points, some even in trees on hilltops, giving them a full sweep as far as they could see. These trails were alive with machine gun and snipers' fire and even after an objective had been taken you would receive their fire from all sides as well as back of you from their concealed "nests." This natural stronghold was strengthened tenfold by their wonderful line of trenches, and their mammoth dugouts that extended so far into the bowels of the earth that even aerial bombardment could not affect them.

The Germans had taken advantage of all this by interlacing its ravines, mountains and wooded slopes with barbed wire entanglements and small tripwires in such a manner that every inch of that ground was a helltrap of its own. Every art known to these past masters of "The Art of War" was brought into play to make this one point invulnerable.

The first "trap" or "pocket" in which we were caught came about as the result of the 92nd Division (a negro unit) retiring a distance of from two to three kilometers after encountering stiff resistance from the Germans on September 28th. This left a large gap on our left flank, which they had formerly occupied, and the Germans immediately took advantage of this and closed in on us cutting us off before we realized that the 92nd had fallen back.

The French Division which replaced the 92nd Division was unable to regain this captured ground as the odds against them were too great.

We were in that "trap" September 28th, 29th and 30th, and were reunited with the rest of the division on October 1st. On the night of October 2nd the battalion was again caught in another "trap," which lasted for a period of six days and nights. It is needless to say that the men suffered greatly during these periods until the balance of the division fought their way through to them.

During the day of October 2nd, Company A (of which I was a member) was badly cut up while taking a small hill, and during the attack we lost 90 men in less than 30 minutes fighting. About 40 members of the company, including myself, were sent back by Major Whittlesey to establish posts of communication and to act as stretcher bearers, as men were being wounded faster than they could be handled. Eighteen of the company remained with the Major and were caught in the second trap.

We fought desperately during those six days, going "Over the Top" as often as three times in one day. That you may have some idea of the cost of the ground taken in those Argonne Woods, can give you the facts of my own company of which I have an intimate knowledge. We went "Over the Top" on the morning of September 26th with 250 men, and on the night of October 15th there were only 44 of us followed Major Whittlesey out of the front lines to the second lines of support near Grand Pre.

.

A LEADING New York newspaper that should have known better, since a score of its pre-war staff were officers in the 77th Division, suggested the other day that Lieutenant Colonel Whittlesey might have been driven to suicide through a feeling of guilt for having led the "Lost Battalion" into a trap in the Argonne ravine since famous as "The Pocket." But since all America is so fully misinformed not only concerning Whittlesey, but as regards most everything else that took place in the A. E. F., it would be unjust to single out one newspaper for criticism.

Every overseas veteran knows that the folks back home are crammed full of bunk about things that happened in France. When we first came back some of us tried to correct these errors when first we heard them repeated, but it didn't take long for us to realize that our fellow citizens resented having the myths exploded. They wanted to believe the foolish and improbable things they did believe.

So today probably a hundred million people believe that the Lost Battalion was lost and that when summoned by a German officer to surrender the gentle, but heroic, Whittlesey replied: "Go to Hell." It may be that Cambronne uttered the words at Waterloo that Hugo says he did. Perhaps Farragut cried "Damn the torpedoes" at Mobile, but we have Whittlesey's own word that he never said "Go to Hell" in the Argonne.

What he actually did was so much finer, and in character with the man, that it should not be lost to the world in the musty files of the War Department.

To understand what brought about the so-called Lost Battalion's advance, and its resultant pocketing by the Germans, one must realize that after seven days' continuous fighting in the Argonne the 77th Division on October 2, 1918, found its advance checked before the heavily-entrenched German positions. The success of the American operations depended upon breaking through the enemy line.

In the face of this impasse the then Major Whittlesey, commanding the First Battalion of the 308th Infantry, received from his commanding officer, Colonel Stacey, an order to attack which contained this sentence: "The general says you are to advance behind the barrage regardless of losses." How strictly the heroic major complied with his orders is testified to in the undramatic language of his official Operations Report written October 9th, the day following his relief. He writes: "The advance was continued to the objective stated, which was reached at 6 p.m. with about 90 casualties from M. G. fire. Two German officers, 28 prisoners and 3 machine guns were captured. His trench system was crossed, one heavily wired."

Here then we have Whittlesey and his composite battalion on their objective---the Pocket---under competent and mandatory orders. This answers the question raised by the New York newspaper quoted above as to whether the lawyer-soldier might not have been driven to suicide through a feeling of guilt for having led his men into a trap. He led them there because he was ordered to, and his later troubles resulted from the inability of units on his right and left to make advances equal to his. He and his command, therefore, were left "up in the air."

Having reached his objective there were two good reasons why he could not have retired to safer ground even had he wished to. In the first place he had received orders to hold his position until the other elements came abreast of him. But they were unable to do so. In that situation the Germans filtered through on either flank, got in his rear, and strung wires across the path through the ravine, thus linking up the two sections of the German trench system, and placing a closed German line behind Whittlesey.

It is of interest to know that the officer commanding the Germans in Whittlesey's rear was from the United States. He was Lieut. Heinrich Prinz, 76th Infantry Reserve Division, and he had lived for six years in Seattle, Wash., prior to the World War. While the Americans clung to their hillside for five days, under constant fire from rifles, machine guns, artillery, mortars and hand grenades--- several false orders were found to be passing down the American lines. On one occasion at least some one was heard to cry out in English, with a German accent: "Gaz masks." It may well be that the former citizen of Seattle was the one who was giving these orders.

Lieutenant Prinz was the man who wrote the note to Major Whittlesey demanding his surrender on the ground of humanity, in order to save further casualties to the surrounded American forces.

There had been casualties, serious ones. Give note to this significant sentence from the Operations Report of Captain Barclay McFadden, Company A, 308th Infantry: "On the 8th of October the Pocket was relieved and all that remained of A Company which could walk back were three men."

A great many word pictures, at the time and since, have been painted of the Gethsemane through which the heroic battalion was passing during those five days. Most of them were fanciful, based on stories told by self-nominated heroes or by artists in words who were not there. In this connection it is interesting to read what the chief actor in the drama was writing himself, and sending back to headquarters by his carrier pigeons, the only line of communication left open.

Pigeon No. 1---"We are being shelled by German artillery. Can we not have artillery support?"

Pigeon No. 2---"Our posts are broken, one runner captured. Germans in small numbers in our left rear. Have located German mortar and sent platoon to get it. E Company met heavy resistance---at least 20 casualties."

Pigeon No. 3---"Germans are on cliff north of us and have had to evacuate both flanks. Situation on left flank very serious. Broke through two of our runner posts today. Casualties yesterday 8 killed, 80 wounded. In the same companies today 1 killed, 60 wounded. Present effective strength of companies here 245." (Whittlesey went in with 679 effectives.)

And so the story ran until his last pigeon was released on October 4th. After that he went militarily dumb. His last message read: "Men are suffering from hunger and exposure and the wounded are in very bad condition. Cannot support be sent at once?"

Four days were to elapse, however, before the desired relief was able to battle its way to the beleaguered forces lying in their funk holes on the exposed hillside. They were days of hunger as well as danger and death from bullets. The men had gone in with only their iron rations. Efforts were being made by American airplanes to drop packages of food for the men but in each instance the food fell outside the lines. This led indirectly to the written demand for surrender from Lieut. Heinrich Prinz. But before going into that it should be explained that, in order to mark his position for the American aviators, Major Whittlesey had placed in position the white cloth panels employed in the Army for such a purpose. These later were to play a part in the drama.

It was tantalizing to the suffering, hungry men to see the precious food meant for them falling outside their position. Nine men, without asking permission, went out into No Man's Land to search for some of the fallen parcels. They paid a heavy penalty. Five were killed, four captured. Among the latter was private Lowell R. Hollingshead. These men fell into the hands of the German forces commanded by Lieutenant Prinz. The latter already knew by observation and reconnaissance what extremities the Americans were in. With some difficulty he compelled Private Hollingshead, blindfolded, to carry a note to Major Whittlesey demanding surrender.

The note was couched in polite terms, praised the bravery of the Americans, and wound up with a demand for surrender in the name of humanity.

We now approach the moment when in the apocryphal histories of the event Whittlesey cried: "Go to Hell." That would have been what our French allies call a beau geste and certainly no American soldier, or civilian, would condemn the major had he indulged in some profanity at the moment. Fortunately, we have the major's own words for what actually occurred. Writing in his official Operations Report he says: "At 4 p. m. a private from H Company reported that he had left without permission in the morning with eight others. They encountered a German outpost. Five of the nine were killed, the rest were captured. This man was given by the Germans a demand for our surrender, a copy of which is hereto attached. He was then blindfolded and returned to our lines. NO REPLY TO THE DEMAND TO SURRENDER SEEMED NECESSARY."

Undramatic you will say, but then those of you who were in it know the United States Army doesn't go in for drama. But, to continue in the language of the stage, there is restrained acting that our better critics deem superior to the fustian and claptrap which so wins the gallery. That was the school of Whittlesey. In the message sent to him by the German officer he had been asked to display a white flag if he meant to surrender. Whittlesey's answer to that was an order to take up the white cloth panels that marked his position to his own airplanes. In doing that he cut his last connecting link with the American army, knowing when he did it that this action might delay, and perhaps prevent, his rescue.

|

TO the Commanding Officer---Infantry, 77th Division. "Sir:--The bearer of this present, Private Lowell R. Hollingshead has been taken prisoner by us. He refused to give the German Intelligence Officer any answer to his questions, and is quite an honorable fellow, doing honor to his Fatherland in the strictest sense of the word. "He has been charged against his will, believing that he is doing wrong to his country to carry forward this present letter to the officer in charge of the battalion of the 77th Division, with the purpose to recommend this commander to surrender with his forces, as it would be quite useless to resist any more, in view of the present conditions. "The suffering of your wounded men can be heard over here in the German lines, and we are appealing to your humane sentiments to stop. A white flag shown by one of your men will tell us that you agree with these conditions. Please treat Private Lowell R. Hollingshead as an honorable man. He is quite a soldier. We envy you. The German Commanding Officer." |

Written expressly for this publication by Private Lowell R. Hollingshead, captured by the Germans and forced to deliver to Lieut. Col. C. W. Whittlesey the German "Demand for Surrender."

ON the morning of October 7, 1918, we were lying on a bleak and barren war-scarred hillside in the Argonne Forest, having been separated from the rest of our command for a period of five days, all of us weakened from lack of food and continuous fighting. About ten o'clock a Sergeant came over to where myself and several comrades were lying in our funk-holes and told us the Major (meaning Major Whittlesey) had asked that eight men volunteer to try and get through to our support lines, to report our condition and get rations. I, among others, having visions of food and rest, volunteered to go. I did not at the time know the Sergeant's name nor have I ever been able I find out what Company he was with or from whom he received his orders to start us out on this fool's errand. I only know that had one driving thought, and that was the desire for food and anything that would help me secure it was all the incentive needed

Through a light fog and mist myself and seven comrades started in the general direction of our support lines and crept down the hillside leading away from the beleagured battalion. We crossed a narrow valley and some of us waded and some of us stepped across a small stream of water known as Charlevaux Creek. Though we were badly in need of water none of us dared stop for even the smallest fraction of second, so went hurrying on to the shelter of the forest which lay the other side of the valley. In a few minutes we were at the edge of the forest, and with a silent prayer of thanks all huddled down for a brief rest. We were very weak from lack of food as we had gone five days in this second "pocket" or trap without any. Prior to that we had been in the first "pocket" or trap for a period of three days and as there was only one day intervening between the two traps we were virtually without stimulant for a period of a week.

Imagine yourself in your own home, even with all modern twentieth century conveniences going without food for a like period and make your own comparison between this and our little gang who had not only gone without food and water, but who for the greater part of that time had been lying out in the cold October rain in muddy funkholes with wounded and dead lying all around us, fighting off attack after attack from the enemy and thinking each minute our last. But to go on with what happened, there was one man among the eight of us who was a full-blooded Indian from Montana and we delegated him as our leader and guide, as several times while crossing that little valley he had kept us from taking wrong paths or trails. Our very lives hinged on every wrong or right move that was made and it was only quite natural that we had a great deal of confidence in him and requested him to take the lead and guide us the rest of the way.

After resting awhile we started up a path in the forest with the Indian now leading us. He only permitted us to go short distances and then take rests to preserve what little strength we had left. We moved very carefully, going quite a bit of the way on our hands and knees. It was right after one of these rest periods when we were again moving that the Indian stopped short and motioned for the rest of us to halt by raising his hand high above his head, and I knew then the Indian had scented danger

We stopped dead in our tracks and in a silence so dense you could hear your own heart beat, the machine guns suddenly started their deadly "rat-tat-tat" and we all dropped flat to the ground. We did not know where the firing was coming from, we only knew it was close and as the bullets began to cut away the brush and twigs around us, knew they had our range, yet we dared not move.

For the next few minutes we were in the midst of a terrific machine gun barrage, it fairly rained lead. As the bullets came closer and closer I noticed little spurts of dirt kicking up ahead of and around me and wondered to myself "What will happen next?" Then wondered how the other boys were faring, and even had a despairing wish that I was back with the rest of the battalion on the hill. Just about that time a peculiar feeling or sort of chill came over me and I thought "this is the last" and fell into a sort of coma or daze. I have no idea how long that deadly "rat-tat-tat" of the machine guns kept up, it may have been for only a few minutes or longer but it seemed like eternity to me. In my half dazed condition, with every shot I felt that some riveter of rivets was using the back of my head to drive his rivets in. I had no idea how many, of the other fellows were alive, but I did, know that the boy directly in front of me was dead as I had seen the jagged bullet holes in his head, although I do not remember him stirring or even uttering a sound.

Then the thing that came into my mind was "what shall I do now?" I was afraid to move for fear the Germans would start their murderous fire again, but just about that time a German appeared from behind a bush not six feet from me and held a long Luger revolver leveled at my head. It is an actual fact that the barrel of it looked to me at that time as large as a shot gun.

The German half smiled, half sneered and I instinctively raised my hands and said the only German word I knew, "Kamerad." Perhaps a second passed between the time I said "Kamerad" until he slowly lowered his gun, but it seemed several lifetimes to me and I can never tell you all the thoughts that passed through my mind in that brief space of time. I do however, distinctly remember that my first thoughts were of my Mother, Dad and home and then a review of all my kid days and a multitude of thoughts too numerous to mention flooded through my mind and a whole pantomime of my life paraded through my brain like a swift moving motion picture. After the German lowered his gun he smiled a great big smile, and what a lovely looking German he was. As he stood there in his gray uniform fully six feet tall, his smile seemed to broaden and broaden then he started walking toward me. I suppose the reason his smile is still in my mind is because it was so unexpected, as I had been taught to hate and expect fearful things from the Germans should they ever capture me. I do not honestly believe there was ever any real hatred in my heart for the Germans or anyone else, and I have yet to hear any man who was actually "IN IT" say he ever had hatred in his heart. I have, however, heard many men who went through it all say that, their outstanding feeling was one of self pity rather than anything else.

The German stepped over to me and' started talking in his own language and pointed at my leg. I half turned and looked to where he was pointing and saw blood spouting from my leg near the knee. For the first time I realized I had been hit. Then other Germans appeared and began looking at my comrades and then I knew how they had fared. Of my seven Buddies I found four had been killed outright and all the rest wounded. Our Indian guide was one of those who had been killed. With this realization a sickening sensation came over me and I thought to myself "this is not real, it is just a dream."

My three comrades were more seriously injured than I and the same German who captured me put my arm around his shoulder and I half hobbled and was half carried over to where the machine gun sat which had played such havoc with us. The other Germans carried my comrades over. They held a consultation and finally sent one of their men back to get instructions as to what to do with us. While he was gone I had an experience that I believe no other American prisoner had, and that was to have the gunner, who had shot me down show me how they worked their machine guns, even going so far as to demonstrate by shooting in the general direction of the hillside where our Battalion lay. By this time the German Runner had returned and motioned for me to get up and started walking back through the forest with me, while other Germans carried my three comrades on improvised stretchers. Having to be carried it was necessary for them to stop often, and as I was able to make better progress went on ahead and did not see them any more. I felt more God-forsaken than ever without my Buddies. After we had gone a short distance I was turned over to another guide and a little farther on another, and in this way was relayed back to German headquarters. The first thing each new guide would do was go through my pockets but none of them took any of my belongings. I was duly thankful for this as we all carried some little insignificant things which we treasured highly. The one thing that interested all these different guides was my Gillette razor and they all wanted it. Two of them offering to buy it and another to trade his straight razor for it, but when I made known by gestures that I had declined, he put it back in my pocket.

Quite a distance from German Headquarters I was blindfolded and the bandage was not taken from my eyes until I arrived there. I entered what was apparently an ordinary dug-out in the side of the hill, but the minute I passed through the outer entrance I got the surprise of my life, for it was an enormous dug-out and very completeIy furnished, being divided into small rooms having board floors and walls. I was taken to the best furnished of all the rooms. On a beautifully carved table was a typewriter, a phonograph, several chairs and a comfortable couch in the room all went to make the place as cozy and homelike as a front line dug-out could be made. As I was greeted by a well dressed and handsome German Officer I could not help but make a comparison in my mind between this comfortable dug-out and immaculately clothed Officer and our Officers lying out on that cold and barren war-strafed hillside, and for the first time I had a feeling of deep resentment.

This Officer turned out to be Lieutenant Heinrich Prinz and addressing me in perfect English, his first question was., "How long since you have eaten?" and I replied, "five days." He said, "Poor devil, you must be starved." And I answered, "I certainly am." He then called an orderly to whom he spoke and who hurriedly disappeared. Prinz told me to lie down, but before doing so he gave me a gold tipped cigarette from a box which sat on his table and we were for all the world like host and guest rather than an officer and captured enemy soldier.

While I was resting a Doctor appeared from an interlocking dug-out and dressed my wound, and just as he was finishing, the orderly whom Prinz had previously sent out returned with a pail full of vegetables, meat and what-not swimming in vinegar. Also he had a large loaf of dark German war bread. He laid all this on the table before me and without any more adieu I went to it.

While I was eating Prinz and two other officers started asking me questions about our outfit, but finding it of no avail as I was still hungrily gulping down the food and between bites told them I was too busy to talk then. In the meantime my leg started bleeding terribly and paining me so that I hardly cared what happened. Prinz called the medical officer again who undressed the wound, placed something on it that seemed to stop the bleeding and then placing a turniquet above the wound, bade me lie down on the couch again.

Then Prinz started asking me questions in earnest. He was very kind about the whole affair and at no time did he or any of the Germans with whom I came in contact treat me roughly or in any way abuse me. Prinz asked me what State I was from and I said "Ohio," he said, "Oh yes, I have been there to Cincinnati." And then he told me he had been in business for six years in Seattle, Washington. He said that he greatly admired the courage of our men on the hill and felt sorry for them. He then tried to find out how much ammunition we had, the number of men, etc., but I would not answer any of the questions and could not if I would. He then told me to come with him and led me to the mouth of the dug-out and handed me a powerful pair of glasses and asked me if I could locate our men on the hillside, all of which appeared very clearly through the glasses to me; but I said I could not as I was mixed up in my directions and he laughed and said, "Oh, I see, as you Americans say, you are a little entangled." Then he led me back into the dug-out again, by this time my head was beginning to go round in a whirl as I was quite weak from loss of blood. Noting my condition he asked me to lie down again and rest, which I did. It was then about two or three o'clock in the afternoon.

He went to his typewriter and started typing and when he had finished he asked me if I would take a letter back to my Commanding Officer. I told him I would like to read it first and he handed it to me. This letter was the "Demand for Surrender." Then I told him I would go after I was rested. I do not know what possessed me to say that, except that I wanted to turn it over in my mind and for reasons unknown even to myself was stalling for time. It seemed like a dream to me to be sitting there captured and having this German Officer ask me to take back to my own Commander this request for surrender. I was just dozing off to sleep when Prinz touched me on the shoulder and said, "If you are to get the message back before dark you must start now." And I replied, "I am ready."

He then placed the letter securely In my pocket and going to a corner of the dug-out brought forth a cane which he handed me saying, "This will aid you in walking." (That cane is still one of my dearest treasures.)

Next he went to the Doctor's dugout and came back with a white cloth which he tied to a stick and said it would be my protection while crossing No-Man's Land. It was to serve as a flag of truce. Then he called one of his men telling me this man would guide me through the German Lines to their fartherest outpost, and he said he would notify his outposts to look out for me and not shoot at me, then giving me two packages of his cigarettes and what was left of the bread that had been brought for me to eat, he again placed the bandage over my eyes and bade me good-bye. I started out with my guide leading me. I liked this guide because he was very careful that I did not stumble over any rocks or other obstacles, and he tried to talk to me but I could not understand him.

In a little while we stopped and I was left standing alone. Being very much exhausted I lay down and soon a German soldier came and threw an overcoat over me. I was thankful for this as I was really chilly but I do not know whether this was done to protect me from the cold wind or to conceal me from the sight of any of our planes that might happen that way at any time.

After I had lain there a few minutes I heard several Germans talking excitedly and then very suddenly and very near me a machine gun broke loose and for a short space of time I thought I was being murdered. However, I soon discovered the bullets were not coming my way and once more life seemed sweet, even to a wounded prisoner in the German Lines. I never knew at what they were firing but soon the firing ceased and my guide came and helped me to my feet and we continued on our way.

I have no idea how far we walked but at last we came to a halt and my guide removed the bandage from my eyes. I was much surprised to find that we were on a road as I remembered no road in that part of the forest. He pointed straight down the road and I knew he meant for me to travel that way. He smiled and spoke a few words in German to me and we shook hands. Then I started across No-Man's Land alone, limping along on my cane, blood soaking through the bandage on my leg, almost at the point of exhaustion, exposed to plain sight of both armies, I could not drive away the thought, "This is the end of my world."

I had not gone far when I came to our own outpost and was halted

by one of our sentinels who asked me who I was and, where I had

been. I told him I had come from the German Lines and had a letter

for Major Whittlesey. He called a Lieutenant who took me to Major

Whittlesey to whom I presented my letter, after reading it and

hearing what had happened to me, Major Whittlesey told me to go

lie down and rest, so I went to my funk-hole and immediately fell

unconscious.

![]()

Written expressly for this publication by Abraham Krotoshinsky, runner for Whittlesey, who broke through the German lines with the message that rescued the "Lost Battalion".

As a member of the Lost Battalion, my experiences were as follows:

For five days and nights Major Whittlesey and Captain McMurtry had been sending out messengers in the attempt to get information back to the balance of the 77th Division. Every messenger sent back was either captured or killed by the Germans. Major Whittlesey called for volunteers and I was chosen.

I started at sun-up on a gray, gloomy day already weak from lack of food and already convinced that death would be the only outcome. I didn't care. After five days of being fired at, hope was gone, and all I wanted was peace. Yet there must have been a spark of hope that kept me going.

My worst experience of the day came early in the morning. I was lying just behind the German lines concealed beneath some bushes when a German officer walked by and accidentally stepped on my fingers. I managed to stay quiet, but it took a great deal of effort. It was several hours before I could leave my place of concealment.

All day I was under heavy fire. Every minute I thought they would get me, I expected death, but I thought of it only as a physical thing, nothing more. I thought of nothing but the necessity of getting that message through. Home, friends, memories, those things one thinks of in less dangerous places were all forgotten. I was kept busy retracing my route and making detours in the effort to throw the Germans off the track.

At nightfall I stumbled into a deserted German trench. For a moment I lay quiet trying to regain some strength and to discover where I was. Then I heard American voices, and not having the password of the day began shouting, "Hello, Hello." After several minutes of this a scouting group of Americans found me and took me to headquarters where I delivered my message, giving the position and condition of the Battalion.

I was then given food and medical attention and ordered to

return that night as an escort with the relief troops. We reached

our command next morning, where we received a tremendous welcome

from our despairing comrades. I had been gassed and wounded and

was sent to the hospital. Upon my return I was informed by my

Commander that I had received the Distinguished Service Cross.

This was later presented to me in France.