Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993: Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

chuca Illustrat

chuca Illustrat

Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca:

The Yaqui Fight in Bear Valley

chuca Illustrat

Reported from Douglas, Arizona, 'January 10, 1915, that a detachment of American Cavalry sent into Bear, Valley,' 25 miles west of Nogales to observe trails, clashed with a band of Yaqui Indians, captured ten, one of whom died in a hospital at Nogales of wound, according to a telegram from the commander at Nogales.(10)

This terse report from the commander of the Southern Department at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, to the War Department in Washington is the only official record of what some believe is the last fight between the U.S. Army and Indians.

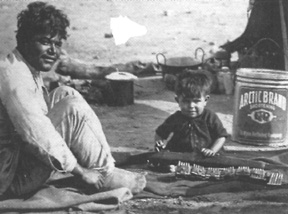

Yaqui Indian Camp at Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico,

in November 1915.

Yaqui Indian Camp at Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico,

in November 1915.

The Yaqui Indians of northern Sonora, Mexico, had for many years been fighting the Mexican government, insisting on their independence. They would commonly cross the border and migrate to Tucson where they would find work in the citrus groves. With their wages they would buy arms with which to fight their revolution and smuggle them back into Mexico. The military governor of Sonora, General Plutarco Elias Calles, had informally asked the U.S. government to help put a stop to that. gun-running.

The Indians route into the U.S. skirted the mining towns ot Ruby, Arivaca and Oro Blanco, not far from the U.S. Army's Camp Stephen D. Little at Nogales. The Indian presence had on several occasions alarmed miners and ranchers in the area who unexpectedly happened upon the Yaquis or found a cow or two butchered on the range. Accordingly, the Nogales subdistrict commander, Colonel J.C. Friers, 35th Infantry, ordered increased patrolling in this area.

-----------------

Yaqui Indians at Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico, in November

1915.

----

----

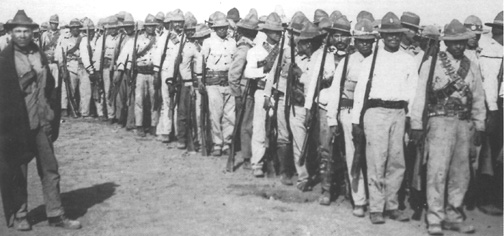

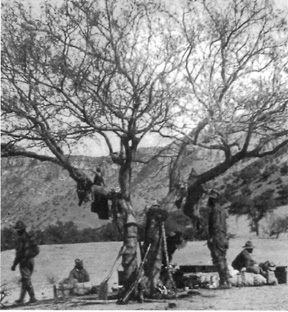

"Yaquis Under Guard. Tuscoso Canyon. Troop E.10th Cav." ----------------Capt. F.H.L

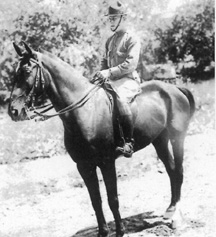

Ryder, mounted, in about 1917.

Photo courtesy F.H.L. Ryder Collection--------------------------------------Photo courtesy F.H.L. Ryder Collection.

Colonel Harold B. Wharfield was a lieutenant stationed at Fort Huachuca at about this time. He researched the events and interviewed participants. His story was published in his book Tenth Cavalry and Border Fights. Here is his account of the fight at Bear Valley.

The 10th Cavalry, with headquarters at Fort Huachuca, had a squadron-size Cavalry camp at Nogales located a half a mile or so up a draw from the 35th Infantry's Camp Stephen D. Little.

The Second Squadron, under command of Capt. Otto Wagner, maintained troop outposts to the east at Lochiel and Campini, and another troop to the west at a strategic natural crossing in the Bow Valley as well as detachments at Arivaca and Oro Blanco.

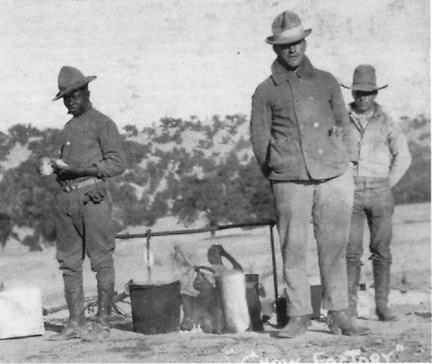

"Chow Factory," Troop E. 10th Cav.. Tuscoso

Canyon. Ariz." Photo courtesy F.H.L Ryder Collection,

---

---

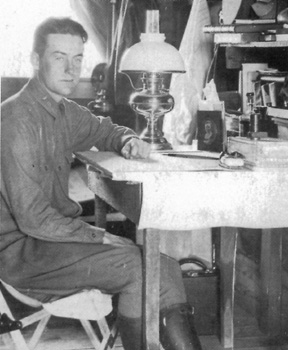

Lieutenant Chuck Close, Arivaca, Arizona, 1918. --------------------"Troop

E, 10th Cav. in the Field, Jan. 9, 1918."

Photo courtesy F.H.L. Ryder Collection.---------------------------Photo courtesy F.H.L. Ryder Collection.

The Bear Valley camp at Atascosa Canyon was located alongside the log corral of the early-day Johnny Vogan homestead. Military information obtained by the Nogales subdistrict indicated that this area was the frequented route used by the Yaqui for their Mexican trail. It was an uninhabited region and a reputed area for people to travel in pairs for safety sake. Various tales---all vague and unconfirmed---were current among the people of Ruby and Arivaca of mysterious disappearances in border country.

After the New Year celebration in January 1918, Capt. Blondy Ryder and his Troop E of the 10th Cavalry drew the assignment to the general vicinity of Bear Valley for border patrol. The troop took the Oro Blanco trail along the border, sending the impediments around by Arivaca and thence southward past Ruby to the Johnny Vogan place. This location was about a mile from the border fence.

The terrain was well suited for the patrol work. A high ridge east from the camp gave a wide view of the region. Here a stationary sentinel look-out was established with visual signal communications in view of a camp sentry. The additional daily patrols rode the trails looking for signs, as well as any wanderers, in the border land.

One day Phil Clarke, a cattleman and Ruby storekeeper, stopped by for a visit. He reported that a neighbor had seen fresh Yaqu signs in the mountains to the north where a winter-killed cow had been partly skinned and sandals cut out of the hide. The next morning on the ninth of January, 1918, Captain Ryder decided to strengthen the observer post by sending First Lt. William Scott along with the detail. They had orders to maintain a constant surveillance of the area with field glasses for any movement along the trails.

About the middle of the afternoon Lieutenant Scott signaled "attention." Upon acknowledgement from the camp sentry he gave the message "enemy in sight," and pointed toward a low ridge west of camp a quarter of a mile or more distant. The sentry hollered to First Sgt. Samuel H. Alexander, who was sitting under a nearby mesquite with several other noncommissioned officers. The shout brought everyone to their feet. On the skyline of the ridge could be seen a long column of Indians crossing to the other side. The horses had been under saddle with loose cinches all day tied up in the corral; so within a few minutes the troop was mounted.

When the soldiers left the corral the Yaquis were out of sight, but Lieutenant Scott kept pointing generally to the south in the direction of the border fence.

"Blondy" Ryder

Galloping up to the crest the troop dropped over into a shallow brushy draw, dismounted, and tied the horses to each other in circles by squad. Leaving a guard, it formed a skirmish line and moved forward up the side of the canyon through the mesquite trees and brush. Nearing the top, nothing was seen of the Indians, so orders were given to return to the horses by a different route. Part way down the canyon the troopers came upon hastily abandoned packs. Sensing that the Yaqui were somewhere in that vicinity, the captain ordered an advance up the canyon in a southeasterly direction. Within only a short distance the hiding Indians were flushed and opened up a hot fire on the soldiers. Luckily the shooting was wild. The bullets could be heard whistling and cracking overhead. Captain Ryder shouted the command to commence firing and keep advancing under cover.

The fighting developed into an old kind of Indian engagement with both sides using all the natural cover of boulders and brush to full advantage. The Yaquis kept falling back, dodging from boulder to boulder and firing rapidly. They offered only a fleeting target, seemingly just a disappearing shadow. The officer saw one of them running for another cover, then stumble and thereby expose himself. A corporal alongside of the captain had a good chance for an open shot. At the report of the Springfield, .a flash of fire enveloped the Indian's body for an instant, but he kept on to the rock.

The Cavalry line maintained its forward movement, checked at times by the hostile fire, but constantly keeping contact with the Indians. Within thirty minutes or so the return shooting lessened. Then the troop concentrated heavy fire on a confined area containing a small group, which had developed into a rear guard for the others. The fire effect soon stopped most of the enemy action. Suddenly a Yaqui stood up waving his arms in surrender. Captain Ryder immediately blew long blasts on his whistle for the order to "cease fire," and after some scattered shooting the fight was over.

Then upon command the troopers moved forward cautiously and surrounded them. This was a bunch of ten Yaquis, who had slowed the Cavalry advance to enable most of their band to escape. It was a courageous stand by a brave group of Indians; and the Cavalrymen treated them with the respect due to fighting men. Especially astonishing was the discovery that one of the Yaquis was an eleven-year old boy. The youngster had fought bravely alongside his elders, firing a rifle that was almost as long as he was tall.

Many years after his Indian fight I asked Captain Ryder, now a retired Army colonel, to give me his recollections of the engagement. In addition to the above factual material he wrote:

... Though time has perhaps dimmed some details, the fact that this was my first experience under fire---and it was a hot one even though they were poor marksmen---most of the action was indelibly imprinted on my mind.

After the Yaquis were captured we lined them up with their hands above their heads and searched them. One kept his hands around his middle. Fearing that he might have a knife to use on some trooper, I grabbed his hands and yanked them up. His stomach practically fell out. This was the man Who had been hit by my corporal's shot. He was wearing two belts of ammunition around his waist and more over each shoulder. The bullet had hit one of the cartridges in his belt, causing it to be exploded, making the flash of fire I saw. Then the bullet entered one side and came out the other, laying his stomach open. He was the chief of the group. We patched him up with first aid. kits, mounted him on a horse, and took him to camp. He was a tough Indian, made hardly a groan and hung onto the saddle. If there were more hit we could not find them. Indians do not leave any wounded behind if they can possibly carry them along.

One of my men spoke a mixture of Spanish, and secured the information from a prisoner that about twenty others got away. I immediately sent Lieutenant Scott, who had joined the fight, to take a strong detail and search the country for a few miles. However they did not find anytbing of the remainder of the band. It was dark when we returned to camp.

I sent some soldiers to try and get an automobile or any transportation at the mining camps for the wounded Yaqui, but none could be located until morning. He was sent to the Army hospital at Nogales and died that day.

"Pink" Armstrong

We collected all the packs and arms of the Indians. There were a dozen or more rifles, some .30-30 Winchester carbines and German Mausers, lots of ammunition, powder and lead, and bullet molds.

The next day when you and Capt. Pink Armstrong with Troop H came in from the squadron camp to relieve us, we pulled out for Nogales. The Yaquis were mounted on some extra animals, and not being horse-Indians were a sorry sight when we arrived in town. Some were actually stuck to the saddles from bloody chafing and raw blisters they had stoically endured during the trip. Those Yaquis were just as good fighting men as any Apache....

Within a week or so we were ordered to Arivaca for station, and had to take our Indian prisoners along because the 35th Infantry colonel, who was also the subdistrict commander, did not want to be bothered with guarding them.

They proved to be good workers and kept the campsite immaculately clean. At the corral nary any droppings were allowed to hit the ground. During the day the Indians would stand around watching the horses. Whenever a tail was lifted, out they rushed with their scoop shovels and caught it before the manure could contaminate the ground. It certainly helped in the decline of the fly population.

"Chuck Close, Bear Valley, 1918." Photo courtesy F.H.L. Ryder Collection.

A few of the Yaquis spoke understandable Spanish, and some of the troopers talked a lot with them. We learned that the reason they fired upon us was they thought the Negro soldiers were Mexican troops that were on the American side of the border. Also, they were traveling in daylight because no United States troops were there three months before when they came into the country.

The Yaquis were so pleased with the routine soldier life, three square meals a day, a cot with a straw mattress, and G.I. blankets at night that they all volunteered to enlist in the Army. But the United States Department of Justice had other plans and took them to Tucson for legal action. That's the last I ever heard of them."

The captured Indians were indicted and tried in the Federal District Court in Tucson. They were charged with "wrongfully, unlawfully, and feloniously exporting to Mexico certain arms and ammunition, to wit: 300 rifle cartridges and about 9 rifles without first procuring a export license issued by the War Trade Board of the United States." Federal Judge William H. Sawtelle dismissed the charges against the eleven-year-old boy, Antonio Flores, and accepted the plea of guilty from the other eight, sentencing them to 30 days in the Pima County jail. The sentence was preferable to the Yaquis who otherwise would be deported to Mexico and face possible execution as rebels.

Footnotes:

10. Annual Report of the Secretary of War, 1918.

11 Wharfield, Harold B., 10th Cavalfy and Border Fights, published by the author, 1965, 8-12.