----

--------

Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca:

Fort Huachuca: The Traditional

Home of the Buffalo Soldier

----

Buffalo Soldier statue at Fort Huachuca's Main Gate.

It was dedicated in 1977 to recognize the part Huachuca

has played in African-American military history.

U.S. Army photo

Henry O. Flipper was the first African-American graduate (1877) of the U.S. Military Academy. The 10th Cavalry officer was dismissed from the service in 1882 after discrepancies were found in the post commissary funds of which he was in charge. Flipper maintained his innocence. He stayed on the Mexican border, serving as a mining engineer and publishing the Nogales Sunday Herald. He later became the interpreter for the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations from 1919-1922, an assistant to the Secretary of Interior, 1922-1923, and an engineer with a New York oil company operating in Venezuela. He authored several books before his death in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1940 at the age of 84. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo.

The story of black Americans fighting under their nation's flag is older than the flag itself. First introduced as slaves by the British early in the 17th century, blacks served alongside their white masters in the first colonial militias organized to defend against Indian attacks.

By the time of the American Revolution, some freed slaves were taking a stand for independence along with the white colonists. A freedman named Crispus Attucks was among those eleven Americans gunned down in the Boston massacre of March 5, 1770, when they defied the British soldiery. When the war broke out, blacks like Peter Salem and Salem Poore were in the thick of the fighting. Salem was credited with shooting the British commander at Bunker Hill and Poore was cited for gallantry. A number of other blacks were serving in New England militia units in 1775, but when the Continental Army was officially formed in 1775, Congress bowed to the insistence of the southern slaveholders and excluded blacks, free or slave, from service. These regulations were soon overridden by the necessities of the desperate fighting and the need for manpower. Black veterans were retained and new recruits were accepted.

"A Halt to Tighten the Packs," Frederic

Remington

In all, there were approximately 5,000 blacks who served in the American Revolutionary War. Despite the fact that they continued to make real military contributions in the War of 1812 and in the Civil War, it was not until after that latter war that blacks were accepted into the regular Army.

Fort Huachuca, more than any other installation in the U.S. military

establishment, was at the heart of half a century of black military history.

It was here that black soldiers came to reflect upon their worth, to remember

the part they had played in taming Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, and Sioux; in

punching a hole through Spanish lines on a Cuban hilltop so Teddy Roosevelt

and his Rough Riders could dash through it; and in winning the day against

Mexican forces at Agua Caliente in 1916. If their white fellow Americans

did not show them the respect they deserved, their foes in battle did. The

Indians called them "Buffalo Soldiers." The Germans in World War

I referred to them as "Hell Fighters."

Fort Huachuca, more than any other installation in the U.S. military

establishment, was at the heart of half a century of black military history.

It was here that black soldiers came to reflect upon their worth, to remember

the part they had played in taming Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, and Sioux; in

punching a hole through Spanish lines on a Cuban hilltop so Teddy Roosevelt

and his Rough Riders could dash through it; and in winning the day against

Mexican forces at Agua Caliente in 1916. If their white fellow Americans

did not show them the respect they deserved, their foes in battle did. The

Indians called them "Buffalo Soldiers." The Germans in World War

I referred to them as "Hell Fighters."

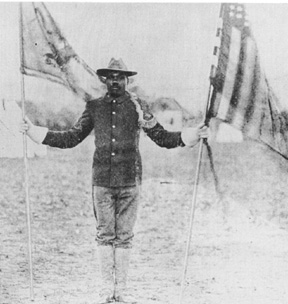

Sergeant George Berry of the 10th Cavalry who planted the colors of the 10th Cavalry on San Juan Hill, Cuba, 1 July 1898. [ He is holding those same colors and standing in front of the headquarters at Huachuca.]

It was on Huachuca's parade field that they felt the stirrings of pride that only the soldier knows, and they marched with a growing sense of equality that their brother civilians would not be allowed to feel until decades later. Problems of discrimination were as widespread in the Army as they were in other parts of American society, but minority barriers fell faster in the Army where the most important measure of a man is his dependability in a fight.

In 1866 six black regular Army regiments were formed. They were the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. Three years later, as part of a reduction in the size of the Army, the 38th and 41st were consolidated to form the 24th Infantry and the 39th and 40th made up the new 25th Infantry. Officered by whites, these regiments went on to justify the belief by black leaders that men of their race could contribute mightily to the nation's defense. Some of the service of each of these regiments in the latter part of the 19th century is highlighted in the paragraphs that follow.

The 24th Infantry Regiment participated in 1875 expeditions against

hostile Kiowas and Commanches in the Department of Texas. One of the engagements

of this campaign saw Lieutenant John Bullis and three Seminole-Negro Indian

scouts attack a 25-man war party on the Pecos River. Sergeant John Ward,

Private Pompey Factor and Trumpeter Isaac Payne were rewarded with the Medal

of Honor for their exceptional bravery in this encounter.

The 24th Infantry Regiment participated in 1875 expeditions against

hostile Kiowas and Commanches in the Department of Texas. One of the engagements

of this campaign saw Lieutenant John Bullis and three Seminole-Negro Indian

scouts attack a 25-man war party on the Pecos River. Sergeant John Ward,

Private Pompey Factor and Trumpeter Isaac Payne were rewarded with the Medal

of Honor for their exceptional bravery in this encounter.

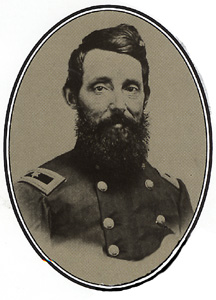

General Benjamin H. Grierson in 1863. Grierson had earned a reputation as a daring cavalryman during the Civil War and was named the commander of the newly formed 10th Cavalry regiment, the Buffalo Soldiers, in 1866.

The 25th Infantry Regiment spent its first ten years in Texas building and repairing military posts, roads and telegraph lines; performing escort and guard duty of all description; marching and counter-marching from post to post; and scouting for Indians. In 1880 the regiment was ordered to the Department of Dakota and stationed at Fort Missoula, Montana. It participated in the Pine Ridge Campaign of 189091, the last stand of the Sioux, and quelled civil disorders in Missoula during the Northern Pacific Railroad strike in 1894.

The 10th Cavalry Regiment, or "Buffalo Soldiers," is probably the most renowned of the black regiments. At its inception, the commander, Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, was determined to fill the ranks only with men of the highest quality. Orders went out to recruit none but "superior men ... who would do credit to the regiment." The 10th's record in several Indian War campaigns attests to the fact that Grierson achieved his goal. In 1886, the Buffalo Soldiers tracked Geronimo's renegades in the Pinito Mountains in Mexico and several months later ran down the last Apache holdout Mangas and his band.

In 1890 the Battle of Wounded Knee Creek, the last major fight of the Indian Wars, pitted the U.S. 7th Cavalry against Big Foot's Sioux. The 9th Cavalry Regiment also took part in this campaign and played a dramatic part in the Battle of Clay Creek Mission. Over 1,800 Sioux under Little Wound and Two Strike had encircled the battle-weary 7th. The situation looked grave until the 9th Cavalry arrived on the field and drove off the Indian force with an their rear. For conspicuous gallantry displayed on this occasion, Corporal William O. Wilson, Troop 1, 9th Cavalry, was granted the Medal of Honor.

Frederic Remington. "Saddle Up"

The paths of all four of these regiments would intersect in a scenic

canyon in southeastern Arizona, just twenty miles from the Mexican border.

The place was called Fort Huachuca and it had played an important part in

the Apache campaigns since its establishment in 1877.

The paths of all four of these regiments would intersect in a scenic

canyon in southeastern Arizona, just twenty miles from the Mexican border.

The place was called Fort Huachuca and it had played an important part in

the Apache campaigns since its establishment in 1877.

The first black regiment to arrive at Huachuca was the 24th Infantry which sent companies there in 1892. During the next year, the entire regiment would come together at the fort. Here they remained until 1896, a year that saw some excitement for the troops who thought that the Indian Wars were ended. It was in that year that Colonel John Mosby Bacon took Companies C and H, of the 24th Infantry out of Fort Huachuca to run down Yaqui Indians who had been raiding around Harshaw and Nogales. The search for these Mexico-based Indians proved inconclusive.

"Dismounted Negro, Tenth Cavalry," Frederic Remington

Companies A and H of the 25th Infantry regiment took up residence in Huachuca Canyon in 1898, after returning from fighting in Cuba, and A Company remained there until the end of April 1899.

Troops of the 9th Cavalry joined the 25th Infantry at Fort Huachuca in 1898 and rotated its units in and out of the post until 1900. A detachment of the 9th would return briefly for a short tour in 1912.

Although the 9th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments had all served briefly at Fort Huachuca during the 1890s, it wasn't until the 10th Cavalry, or the "Buffalo Soldiers," arrived there in December 1913 that the continuous era of black soldiers began at Huachuca. (The nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" was first given to the men of the 10th Cavalry by the Indians of the plains who likened their hair to that of the buffalo. Over the years this name has been extended by veterans to include soldiers of all of the original black regiments.)

This proud cavalry unit had served in Arizona before, in the last century,

rotating from one post to another in Arizona, New Mexico or Texas, wherever

they were needed to track down Apache renegades. So the startling vistas

were not new to many of the veterans. Nor was the relentless desert sun

a stranger to these horsemen who doggedly followed the trail of Pancho Villa

into Mexico in 1916. In Huachuca Canyon they found a home for the next eighteen

years, the longest this mobile unit would stay at any one place since its

formation in 1866.

This proud cavalry unit had served in Arizona before, in the last century,

rotating from one post to another in Arizona, New Mexico or Texas, wherever

they were needed to track down Apache renegades. So the startling vistas

were not new to many of the veterans. Nor was the relentless desert sun

a stranger to these horsemen who doggedly followed the trail of Pancho Villa

into Mexico in 1916. In Huachuca Canyon they found a home for the next eighteen

years, the longest this mobile unit would stay at any one place since its

formation in 1866.

Men of the 25th Infantry warm themselves around a Sibley stove at Fort Keough, Montana, in 1890-91.

Right after their arrival at Huachuca, in 1914, the men of the 10th were spread out at encampments along the Arizona-Mexico border from Yuma on the West to Naco on the east. They corralled their horses and stretched their tents at points in between like Forrest, Osborne, Nogales, Lochiel, Harrison's Ranch, Arivaca, Sasabe, La Osa, and San Fernando. Many would sweat it out under canvas for as long as ten months before being rotated back to their home station in the cooler elevations of the Huachucas.

They were picketed along the border, not as some training exercise,

but to enforce neutrality laws. Mexico was experiencing political upheaval

on a scale that alarmed statesmen in Washington, D. C., and they quickly

legislated that there could be no encroachments upon American soil.

They were picketed along the border, not as some training exercise,

but to enforce neutrality laws. Mexico was experiencing political upheaval

on a scale that alarmed statesmen in Washington, D. C., and they quickly

legislated that there could be no encroachments upon American soil.

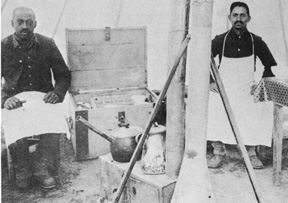

Kitchen scene, 25th Infantry during winter campaign, 1890-91, Fort Keough, Montana. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo (SC83763).

They were relieved in 1931 by the 25th Infantry Regiment. First arriving at the post in 1928, the 25th continued the tradition of black soldiering there. Like the 10th Cavalry, they had seen hard combat in both the Indian Wars and in Cuba. Also like the Tenth, they were to serve there for 14 years until 1942 when they were incorporated as cadre into the newly formed 93d Infantry Division.

The 93d and 92d Divisions trained one after the other at Fort Huachuca

during World War II. The 93d, which would be the first black division to

see action in the war, arrived in Arizona in 1942 and shipped out to the

Pacific in 1944. Because its regiments, the 368th and 369th, were assigned

to the French Army in World War 1, the light blue French helmet became the

division's shoulder patch.

The 93d and 92d Divisions trained one after the other at Fort Huachuca

during World War II. The 93d, which would be the first black division to

see action in the war, arrived in Arizona in 1942 and shipped out to the

Pacific in 1944. Because its regiments, the 368th and 369th, were assigned

to the French Army in World War 1, the light blue French helmet became the

division's shoulder patch.

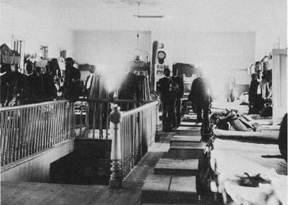

A squad room interior of the 24th Infantry at Huachuca around 1892.

The 92d too had regiments (365th, 370th and 371st) that could trace their lineage to some heroic fighting in France in 1918, but the division chose to reach back to the Indian Wars of the 1870s and 80s for their symbol. They chose for their shoulder patch the buffalo, recalling the "Buffalo Soldiers," as the black troops were respectfully called by the Indians of the Western plains.

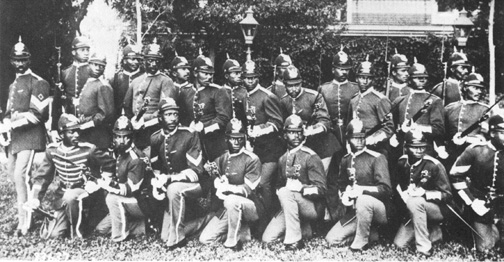

Company B of the 25th Infantry was stationed at Fort

Snelling, Minnesota, from 1883-1888.

They pose here in their full dress uniforms. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo

SC 83637.

To some blacks Huachuca was a mountain refuge far away from the immense struggle that was taking place in America's city streets and country lanes, a fight for equality. But for others it was a way to participate in the struggle, to take up a profession that offered dignity, service to country, and maybe a warrior's death. For whatever reason they joined the Army (the Marines did not admit blacks; the Navy had only a few openings for the menial job of messboy), Fort Huachuca would be an almost inevitable stop along their way. Some found it to be "a very fine place to serve." To others it was "an infamous place." For all it was, for a time, home. Black infantrymen and cavalrymen carved out a place in history there. If the sobriquet "Buffalo Soldier" has come to stand collectively for the black men who served in the four regular army regiments from 1866 to World War 11, then Fort Huachuca has earned the distinction of being "Home of the Buffalo Soldier."

"A Campfire Sketch," Frederic Remington------------------"A

Pull at the Canteen," Frederic Remington