Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions

I. Discovery of the Proto-Sinaitic

Inscriptions:

A. Sir

William Flinders Petrie A. Sir

William Flinders Petrie

Up to the beginning of this century, the Mesha Stele (Moabite Stone,

a royal inscription of a king of Moab named Mesha, ca. 850 BCE) was the

earliest known alphabetic inscription. Speculation on the origin of West

Semitic alphabets was based largely on the Bible, or traditional attempts

to reconstruct the past.

In the winter of 1904-1905 Sir Wm. Flinders Petrie discovered the inscriptions

at Serabit el-Khadim that became known as Proto-Sinaitic. Petrie reached

the conclusion that the inscriptions were alphabetic but made no attempt

to identify any related offshoots. An exhibition catalogue was published

in 1905 and an expedition report in 1906. |

B. Sir Alan Gardiner B. Sir Alan Gardiner

A major breakthrough came with the decipherment of the word b`lt, (B`alat)

by Sir Alan Gardiner in 1916. Gardiner concluded that the Sinaitic signs

were created by reforming Egyptian Hieroglyphic signs based upon their acrophonic

value. His reasoning has been found to be sound and his work continues to

be the foundation upon which progress continues to the present. His early

decipherment's are called the B`alat inscriptions b`lt, (B`alat,  ). ). |

C. Hubert Grimme and A. Van den Branden:

Hubert Grimme stood alone, with modest support from Van den Brenden,

in postulating the existence of a pre-Thamudic alphabet, and rejected the

notion that Thamudic scripts evolved from the South Arabic script. He was

never able to find such a script (possibly because he looked for it in the

wrong desert). Had he looked closer to the birthplace of West Semitic scripts

he may have recognized "Old Thamudic" (Old Negev) which was the

most probable parent of the Arabian scripts.

While Grimme's translations may have some serious defects [the same can

be said of all translations before and since his time] his sign lists showing

the correspondence of Proto-Sinaitic &Proto-Canaanite to Egyptian Hieroglyphic

signs is very helpful and was as well done as any others of more recent

vintage.

Sign Chart of H. Grimme (1923/1988): |

II. The Harvard Expeditions

A. Harvard, 1927

In 1927 a Harvard University Expedition in the Sinai made a side trip

upon their return from Santa Catherina through Serabit el-Khadim. They removed

some inscriptions left by Petrie and delivered them to the Cairo Museum.

They also increased the corpus of Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions by three (Lake,

Blake, and Butin 1928). |

B. Harvard,

1930-35 B. Harvard,

1930-35

The above effort was a prelude to a much more ambitious and well planned

under-taking by Harvard University. From 1930 to 1935 Harvard and the Catholic

University of America worked at Serabit el-Khadim and uncovered ten more

inscriptions from the area (Butin, New, Lake and Barrois 1932; and Butin,

and Starr 1936). |

III. Decades of the 20th Century When

Research Lagged

| It seems possible that during the decades of the thirties through the fifties

West Semitic scholars accepted earlier reconstruction's of alphabetic origins

as solid facts and assumed that all essential questions had been adequately

answered. In the era of this mind set Winnett, of the University of Toronto,

attempted to translate what he called, "Thamudic of the Negev." |

A. Scripts

of Pre-Dialects: Fredrich V. Winnett & Emmanuel Anati, A. Scripts

of Pre-Dialects: Fredrich V. Winnett & Emmanuel Anati,

Winnett was a tireless researcher of the nine or ten pre-Arabic scripts

of the Arabian Desert, among which he spent a major part of his professional

life. He also attempted to reconstruct the emergence, and identify some

relationships, between these alphabets. No doubt his work with pre-Arabic

scripts was excellent but his brief exposure to Old Negev resulted in his

participation in perpetuating the error that the Negev inscriptions were

graffiti left by post Thamudic vagabonds. The extensive research and study

of J. R. Harris & D. W Hone has led to a more probable and substantial

conclusion, i.e. that the Negev inscriptions are Post Proto-Canaanite and

the major parent script of the pre-Arabic Thamudic scripts.

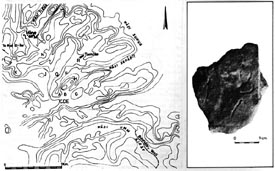

In 1959 Winnett published an article in `Atiqot, Vol. 2, pp. 146-149

titled, "Thamudic Inscriptions from the Negev." The four pages

of this article contained fourteen inscriptions, one of which he pronounced

"Illegible" (No. 10393), two of the remaining thirteen were composed

of three and four lines respectively and the remaining ten were one liners.

The introduction paragraph contained the following information:

The following graffiti (fig. 1. pl. XXII), which Mr. E. Anati has very

kindly allowed me to study, are all of the type which in my study of the

Lihyanite and Thamudic Inscriptions, Toronto, 1937, I labeled Thamudic C

and dated to the 1st or 2nd centuries C.E. (p. 52). They may be as late

as the 3rd century (see A. VAN DEN BRANDEN, Les inscriptions thamudeennes,

Louvain, 1950, p. 24), but in the present state of our knowledge it is impossible

to be more definite (Winnett, 1959, p. 146). No doubt the above collection

was gathered by Emmanuel Anati in April of 1954 & January of 1955 and

was the bases for his articles in P.E.Q. of July/Dec. 1954, "Ancient

Rock Drawings in the Central Negev," pp. 49-57. Jan/June 1956, titled,

"Rock Engravings From the Jebel Ideid (Southern Negev)."

The above site (Jebel Ideid) is now called Har Karkom (of which more will

be said later). Anati called the inscriptions Thamudic-Nabatean, style IV2,

and Winnett called them Thamudic C. 1st to 3rd Cent C.E.. More resent research

has made it clear that neither of the above two men had a clear perception

of the nature and origin of the script in question. |

B. The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and their Decipherment: Wm.

Foxwell Albright (1966)

Albright's publication was a major step forward in that it included transliterations

and translations of all of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions identified up

to that point in time. We have some reservations with Albright's translations

because it is now possible to recognize ligatures and consequently assign

them the several sound values they represent (rather than viewing them as

single signs with an elaborate flourish). Also no-one (in that period) recognized

the clues that signal a word break, but each translator was left to arbitrarily

decide where these breaks should be made. |

IV. Research Revival: Proto-Sinaitic,

Proto-Canaanite & Old Negev:

A. Itzhaq Beit-Arieh (Ophir Expedition):

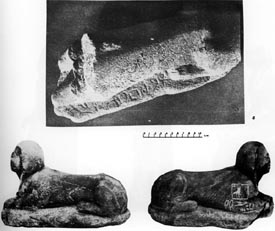

I. Beit-Arieh BAR, Winter, 1982 p. 13.

I. Beit-Arieh BAR, Winter, 1982 p. 16

Beit-Arieh was a Senior Research Associate and Lecturer of the Institute

of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University. Since 1971 he has been the director

of the Ophir Expedition in the Sinai Peninsula. His work at Mine L, in the

Serabit el-Khadim area was of great importance in establishing 1500 BCE

(the cave-in date for Mine L.) as a time when there was a reasonably mature

alphabet, reinforcing the probability that Proto-Sinaitic began to emerge

about 1700 BCE.

Early on, the Ophir Expedition became an extension of the 1927 to 1935

Harvard expedition, not because Harvard had joined them but because they

could see that they had a possibility of successfully dating the Proto-Sinaitic

inscriptions (which had been a major objective of the Harvard project).

Mine L, had not been excavated by Harvard because cracks in the over head

made them fear a cave-in if debris was removed. After appropriate precautions

had been made the Ophir crew began a three week task of removing debris

(1977). Each stone, large or small, "was carefully examined twice before

being discarded" (Beit-Arieh, BA, Winter, 1981, pp. 14-15).

One of the early stones with an inscription carried the name El (God)

and may well be the earliest West Semitic inscription of the divine name.

Other appearances of this special name were also found. A concluding statement

by Beit-Arieh will help to highlight the significance of his work. He wrote:

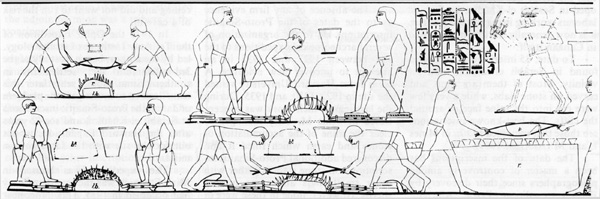

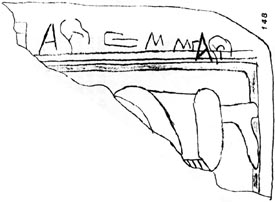

The dating of the above finds is a key issue in the present study, because

only archaeological evidence of this kind can bring us closer to solving

the problem of the period of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions. Since Mine

L contained another inscription besides the one carved on the rock inside

it, we may assume that all the finds are contemporaneous and were buried

at the end of a single mining season. Weighty evidence for dating the find

to the Late Bronze Age (the New Kingdom in Egypt) is a sherd from a bichrome

flask found in the mine. The sherd is burnished and decorated with black

and brown stripes on a light ground and belongs to a class of pottery ubiquitous

in the Near East in the Late Bronze Age between the 16th and 14th centuries

BC. Parallels for axes occur in occupation levels and tombs from the time

of the New Kingdom in some places in Egypt, as well as on wall paintings

depicting their use. . . The ax was probably the symbol of the miners.

. . The many finds of the Late Bronze Age discovered during the clearing

of Mine L. together with the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions discussed here

strongly suggest that the mine was worked and the inscriptions carved in

this period [LBA](Beit-Arieh, 1981, pp. 17-18).

I. Beit-Arieh BAR, Winter, 1982 p. 18.

I. Beit-Arieh BAR, Winter, 1982 p. 18.

B. Benjamin Sass (West Semitic Alphabets)

In 1988 a very important doctoral dissertation was completed at Tel

Aviv University, by Benjamin Sass titled, The Genesis of the Alphabet

and its Development in the Second Millennium BC, Agypten Und Altes Testament,

Band 13, in Kommission bei Otto Harrassowitz, Weisbaden. Sass had been a

student of Beit-Arieh and spent considerable time in the Sinai as a deputy

officer of the Israeli Antiquities Department.

Much of this current, brief scan of important events in the unfolding

history of the emergence of West Semitic alphabets is based on the Sass

dissertation. While working in the Sinai, Sass expanded the corpus of Proto-Sinaitic

inscriptions and also carefully verified several very important inscriptions.

The final impact of his work was best stated in his 7th and last chapter,

page 161, as follows:

The origin of the Phoenician letters [and even more so the Old Negev

letters] in the Proto-Canaanite and Proto-Sinaitic scripts, and the borrowing

of most, if not all, letter forms in the latter script from Egyptian hieroglyphics

on the basis of acrophony are now seen as indubitable facts (cf. Snyczer

1974, 9).

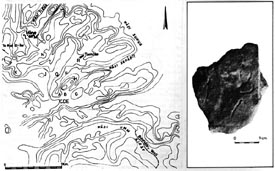

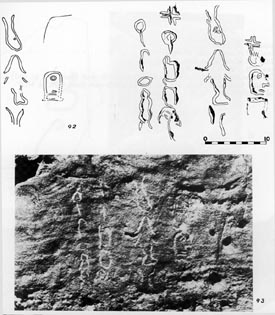

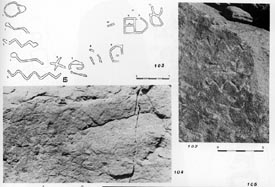

Gerster's #1

(Sass 78 fig. 10) 304. Sinai 380 (Sass 93. Sinai 376 (Gerster

1961, 65 lower)

(Sass 78 fig. 10) 304. Sinai 380 (Sass 93. Sinai 376 (Gerster

1961, 65 lower) |

91. Sinai 376 (Rainey 1975, fig. 1) Sinai 380 1978 fig. 10).

91. Sinai 376 (Rainey 1975, fig. 1) Sinai 380 1978 fig. 10). |

The bracketed insertion in the paragraph above was justified by the research

of Harris and Hone in which they discovered that twenty one of twenty-two

Canaanite/Phoenician sound signs are clearly of archaic origin; i.e., they

retain a clear correspondence to Proto-Canaanite and Proto-Sinaitic.

Out of a shorter list of twenty Old Negev sound signs positions, forty-two

are archaic. The number forty-two is possible because each of the twenty

Old Negev sound positions may have several abstract alternative signs and

several alternative archaic signs. The above short sign lists were used

because their study was confined to signs found in the inscription of the

Land of Canaan, the Negev and the Sinai that were included in their research.

Old Negev has a stronger link to Proto-Canaanite and Proto-Sinaitic than

does Canaanite Phoenician.

|

|

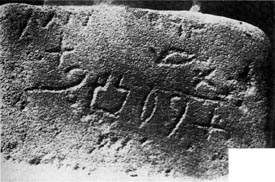

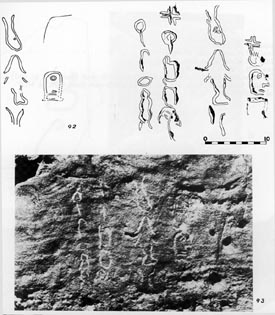

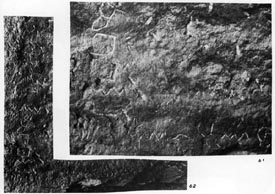

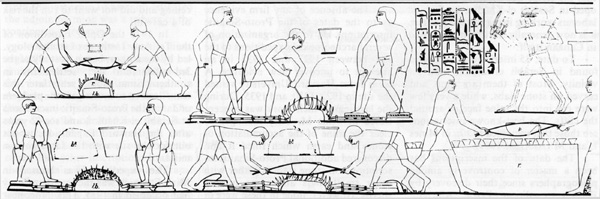

59. Sinai 357 (Beit-Arieh 1978, fig. 6 with modifications by B. Sass)

60. Sinai 357 (courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology Tel Aviv University)

obtained by B. Sass 1988

61. Sinai 357 (courtesy of Prof. I. Beit-Arieh, Institute if Archaeology,

Tel Aviv University) obtained by B. Sass 1988) 62. Sinai 357 (Butin 1936,

pl. 16). |

Sass and Beit-Arieh carefully made an on-site verification of the several

renditions made by earlier scholars of Sinai 357. As a result Harris and

Hone proceeded with confidence to observe in this inscription one of the

earliest uses of identifying word breaks by changing the size or shape of

a letter (in the column letters #'s 12-13). The phrase involved reads,  = "for `Avev."

= "for `Avev."

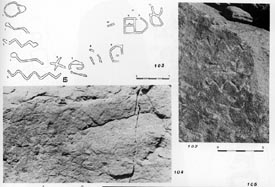

Y. Linder, M. Halloun & M. Sharon (Ancient Rock Inscriptions)

In 1990 the

Archaeological Survey of Israel, project of the Israel Antiquities Authority,

under the direction of Yeshua`yahu Lender, published a two volume series

on the findings of their survey. The first Volume was titled, Map of

Har Nafha (196), and Vol. 2, titled, ANCIENT ROCK INSCRIPTIONS, SUPPLEMENT

TO MAP OF HAR NAFHA (196) 12-01, The so-called "Thamudic"

inscriptions were translated by Dr. Moin Halloun. Although Halloun continued

to refer to this collection of inscriptions as "Thamudic" and

although he translated them as if they were a pre-Arabic dialect, he also

expressed his reservation about the labeling and the dating of the inscriptions.

He said: In 1990 the

Archaeological Survey of Israel, project of the Israel Antiquities Authority,

under the direction of Yeshua`yahu Lender, published a two volume series

on the findings of their survey. The first Volume was titled, Map of

Har Nafha (196), and Vol. 2, titled, ANCIENT ROCK INSCRIPTIONS, SUPPLEMENT

TO MAP OF HAR NAFHA (196) 12-01, The so-called "Thamudic"

inscriptions were translated by Dr. Moin Halloun. Although Halloun continued

to refer to this collection of inscriptions as "Thamudic" and

although he translated them as if they were a pre-Arabic dialect, he also

expressed his reservation about the labeling and the dating of the inscriptions.

He said:

If at one time it was assumed that inscriptions discovered in the Negev

were but the traces of Thamudic tribes passing through the region, particularly

along the main trade routes, this assemblage of inscriptions, as well as

additional inscriptions, published and unpublished, now calls for a reevaluation

of the subject.

Archaeological evidence from the first and second centuries (CE) - the

presumed dates of the inscriptions - is insufficient to establish the history

of settlement in the region, especially insofar as settlement and sedentarization

is concerned. Comprehensive epigraphic research could contribute a great

deal to this complex subject (Moin Halloun, 1990, Vol. 2, p. 36.). |

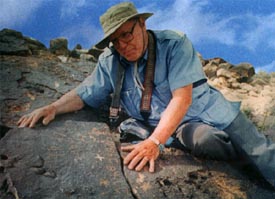

Research of

Harris and Hone, conducted from 1994 to April of 1997, focused on verifying

some of Halloun's photographs and transliteration by an on-site examination.

Their conclusion was that the inscriptions at Nahal `Avedat date to the

period of the colonization of the Negev enacted by the Royal Kings of the

House of Judah to secure safer trade lanes from the Gulf of Elath to the

Mediterranean (six to eight hundred years before the dates suggested by

Winnett). Research of

Harris and Hone, conducted from 1994 to April of 1997, focused on verifying

some of Halloun's photographs and transliteration by an on-site examination.

Their conclusion was that the inscriptions at Nahal `Avedat date to the

period of the colonization of the Negev enacted by the Royal Kings of the

House of Judah to secure safer trade lanes from the Gulf of Elath to the

Mediterranean (six to eight hundred years before the dates suggested by

Winnett).

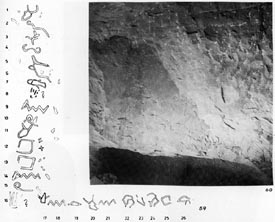

Harris and Hone (aided by Jon & Cindy Polansky) now have a growing

corpus of about 130 inscriptions from the Negev. From a careful examinations

of the twenty two sound signs (each sign having from one to nine alternative

forms) they have concluded that a large number of archaic forms are retained

in use and that this "Old Negev" alphabet is the ancient parent

of the Thamudic scripts. |

D. James Harris & Dann Hone (Expanding the Old Negev Corpus)

Introduction:

Observing the inadequate translations of Winnett, Harris was encouraged

to begin with a careful study of the signs and the result was that the abundance

of archaic letter forms and archaic construction and usage demanded that

this script be considered an early post Proto-Canaanite script and not a

pre-Arabic dialect script. As a post Proto-Canaanite script it was best

translated in Hebrew (i.e. pre Massoretic Hebrew).

In the years that followed James R. Harris and Dann W Hone expanded their

corpus of "Old Negev" inscriptions. They abandoned the misleading

word "Thamudic" because Old Negev (1200 BCE) is the ancient parent

of the Arabian Scripts, while Thamudic (pre-Christian) is a late offspring.

We have discovered

a script in the Negev of Israel that appears to be a local variation of

Proto-Canaanite [a generic formative script widely used among Canaanite

peoples during the second millennium B.C.]. This local variation, which

we call the Old Negev script, was widely used by Negev Canaanites (such

as Kenites and Israelites) from 1200-600 BC. In the interest of not straining

the strong indications from archaeology, inscriptions, and the Bible that

the major carriers of this script were Midianites we call this script Old

Negev and identify its carriers as ancient Canaanite people or peoples. We have discovered

a script in the Negev of Israel that appears to be a local variation of

Proto-Canaanite [a generic formative script widely used among Canaanite

peoples during the second millennium B.C.]. This local variation, which

we call the Old Negev script, was widely used by Negev Canaanites (such

as Kenites and Israelites) from 1200-600 BC. In the interest of not straining

the strong indications from archaeology, inscriptions, and the Bible that

the major carriers of this script were Midianites we call this script Old

Negev and identify its carriers as ancient Canaanite people or peoples.

This Old Negev script not only has a distinctive sign system with features

that go back to it's Proto-Sinaitic parent script but also a grammatical

structure persisting from Proto-Sinaitic through Proto-Canaanite to Old

Negev. These distinctive characteristics were not passed on to Canaanite/Phoenician

or to Old Negev's offspring scripts of the Arabian desert. Therefore these

features will become "ear marks" for the identification of this

script where ever it may be found and must be clearly presented so that

all may judge the certainty of our observations.

With a collection of over one hundred and thirty inscriptions this study

has opened a small window to the early (pre-Exile) history of Canaanite

peoples of the Negev. And since twenty-five percent of the inscriptions

contain names of the God of Israel (Yah, El/Yah, Yahu, and Yahh) it seems

fair to say that these Canaanite speakers had a covenant relationship with

Yahweh. |

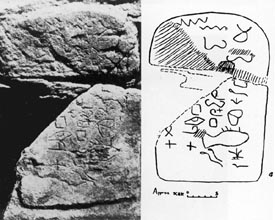

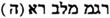

The Shechem Plaque:

Proto-Canaanite:

Old Hebrew:  = Stoned to death for love (of a) Seer.

= Stoned to death for love (of a) Seer.

The second letter

from the right is an intrusive abstract resh placed in the inscription at

some later period, therefore we will simply ignore it. [From Benjamin Sass,

(1988) pp. 56-57, translation by Harris and hone. ] The second letter

from the right is an intrusive abstract resh placed in the inscription at

some later period, therefore we will simply ignore it. [From Benjamin Sass,

(1988) pp. 56-57, translation by Harris and hone. ] |

Some General Characteristics of Old Negev:

Some General Characteristics of Old Negev that were not continued in Canaanite/Phoenician

or in the pre-Arabic scripts of the Arabian Desert.

1. Sign Rotation; the orientation of a sign can signal the reader that,

when in horizontal position, it represents an inseparable preposition or

an article.

2. When in an upside down position it represents the end of a word or phrase.

3. When a letter is larger or smaller than the preceding letters it indicates

the end of a word or phrase.

4. The numbers 2 & 3 above also indicate the direction of language flow.

5. All West Semitic alphabets (emerging after Proto-Canaanite) utilize the

abstracted forms but Old Negev retains in use a very large number of archaic

forms (i.e. Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite forms).

6. Old Negev also retains an elaborate use of ligatures to create symbols

that often complement or enhance the inscriptions. [This form of composition

was especially useful when a population was a mix of literate persons and

persons with varying levels of illiteracy.

Onto The Names of God

= "for `Avev."

![]() = Stoned to death for love (of a) Seer.

= Stoned to death for love (of a) Seer.