Apache Scouts in the Punitive Expedition

Apache Scouts in the Punitive Expedition Apache Scouts in the Punitive Expedition

Apache Scouts in the Punitive Expedition

After Geronimo's surrender, there was less of a need for Indian scouts and, in 1891 the number of scouts apportioned to Arizona was limited to fifty. By 1915 only 24 remained in service. It appears that an additional 17 Apache scouts were enlisted to join Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing's Punitive Expedition into Mexico because in 1916 the number rose to 39, and in 1917 fell back to 22. Apache scouts from Fort Huachuca accompanied the 10th Cavalry and others from Fort Apache joined the l1th Cavalry on their long scouts into Mexico in search of the bandit/revolutionary, Pancho Villa.

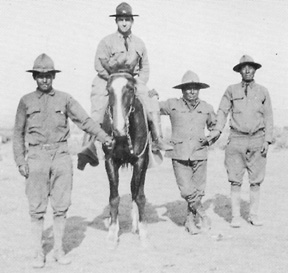

First Sergeant Chicken, Jesse Palmer, Tea Square,

Sgt. Big Chow, and Corporal C.F. Josh, in front of the adjutant's office

at Fort Apache in 1919. Photo courtesy Lt. H. B. Wharfield, 10th Cavalry,

commanding Indian Scouts in 1918-19.

During the Punitive Expedition in 1916, twenty Indian scouts were sent down from Fort Apache to join the 11th Cavalry. They arrived too late to take part in the search for Villa which had been suspended due to the protests of the Carranza government about the U. S. presence on Mexican soil. But they did have ample opportunity to show their tracking skills. Captain James A. Shannon with the 11th wrote an article in the journal of the U. S. Cavalry Association for April 1917, entitled "With the Apache Scouts in Mexico." He described their cautious way of operating.

The Indian cannot be beaten at his own game. But in order to get results, he must be allowed to play that game in his own way. You tell a troop of white soldiers there is a enemy a thousand yards in your front and they will go straight at him without questions. The Indian under the same circumstance wants to look it all over first. He want to go to one side and take a look. Then to the other side and take a look. He is like a wild animal stalking its prey. Before he advances he wants to know just what is in his front. This extreme caution which we don't like to see in the white man, is one of the qualities that makes him a perfect scout. It would be almost impossible to surprise an outfit that had a detachment of Apache scouts in its front.

They do not lack courage by any means. They have taken part in some little affairs in Mexico that required plenty of courage, but they must be allowed to do things in their own way.

James A. Shannon.

The Apaches had a centuries-old hatred of Mexicans and it surfaced during the expedition. Shannon recalled an evening when they encountered some government troops.

...As we approached this outfit and opened a conversation with them, Sergeant Chicken (First Sergeant of the Scouts) fingered his gun nervously and gave vent in one sentence to the Indians' whole idea of the Mexican situation: "Heap much Mexican, shoot 'em all!" There was no fine distinctions in their minds between friendly Mexicans and unfriendly, Carranzistas and Villistas, de facto troops and bandits. To their direct minds there was only one line of conduct-"Heap much Mexican, shoot 'em all!" They had to be watched pretty carefully when out of camp to be kept from putting this principle into practice.

The Apache scouts proved useful in tracking American deserters and on at least one occasion located some of the villistas. They picked up the trail of some stolen American horses that were two or three days old. Shannon writes:

They started off on the trail and after going a short distance came to a rocky stretch where the trail was hard to follow. They circled out like a pack of hounds and soon one of them gave a grunt and all the rest went over where he was and started off again. After a while the trail seemed to divide, so the detachment split up into two parties following the two trails. After about an hour or so, one of these parties overtook the villistas in a very narrow ravine. They shot two of them, and on account of the narrowness of the pass, unfortunately shot two of the horses, one of which proved to be the private horse of Lieutenant Ely of the Fifth Cavalry. They recovered one government horse and got some Mexican saddles, rifles, etc.(78)

Indian scouts Andrew Paxton, Charley Shipp, and Joe

Quintero with Dr. McCloud at Fort Apache in 1918.

New regulations were written to govern Indian Scouts in 1917. The main change from previous regulations were the period of enlistment. Heretofore scouts had been enlisted for at varying times for three months, six months or a year. Now they would sign up for a seven-year hitch like other soldiers. The new regulations provided:

479. Indians employed as scouts under the provisions of section 1112, Revised Statutes, and Section 1, act of Congress approved February 2, 1901, ...will be enlisted for periods of seven years and discharged when the necessity for their services shall cease. While in service they will receive the pay and allowances of cavalry soldiers and an additional allowance of 40 cents per day, provide they furnish their own horses and horse equipments; but such additional allowance will cease if they do not keep their horses and equipments in serviceable condition.

480. Department commanders are authorized to appoint sergeants and corporals for the whole number of enlisted Indian scouts serving in their departments, but such appointments must not exceed the proportion of 1 first sergeant, 5 sergeants, and 4 corporals for 60 enlisted scouts.

481. The number of Indian scouts allowed to military departments will be announced from time to time in orders from the War Department.

482. The enlistment and reenlistment of Indian scouts will be made under the direction of department commanders. The appointment or mustering of farriers or horseshoers on the rolls of Indian scouts is illegal.

483. In all cases of enlistment of Indians the full Indian name, and also the English interpretation of the same, will be inserted in the enlistment papers and in all subsequent returns and reports concerning them.

Colonel Wharfield, a lieutenant commanding scouts in 1918, would later describe how the Apaches were expected to be employed that year.

The Apache scouts were not trained or drilled to maneuver as the soldiers of the army. Their operations were in accordance with the Apache's natural habits of scouting and fighting. The only directions given by the military were general in nature for the requirements of the movements of the troops. On the march small groups of the scouts were out several miles on the flanks and in front, keeping occasional contacts with the main body. At night most of them came in, leaving a few of the scouts posted as lookouts. An Apache never wanted to be surprised, and all of their movements were based on that principle. They approached ridges and high ground with extreme caution, peeking around, looking as far ahead as possible, using cover, and keeping exposure to the minimum. In a fight they did not believe in charging and battling against all odds, which was the quality of many of the Indians of the Plains. Always they sought for an advantage over the foe, and retreated rather than expose themselves to gun fire. These characteristics made the Apache an invaluable scout in the field for operations with troops. Likewise it accounts for the fact that small numbers of hostile Apaches were able to thwart the efforts of the army in so many instances....

During my service in 1918 at Fort Apache the scouts wore cavalry issue clothing shoes and leggins, but some retained the wide car belt of their own construction and design. An emblem U.S.S. for United State Scouts was fastened on the front of the issue campaign hat. The regulation emblem was crossed arrows on a disc with the initials U.S.S.; but I never saw such a design on the scouts' uniform nor in the Quartermaster supply room.(79)

Lieutenant Wharfield talked about some of the scouts who stood out in his memory.

At Fort Apache I had excellent relationships with Chicken. We hunted together for a few days on Willow Creek, branch of the Black River. He was on a manhunt with me after a trooper, who went AWOL and was hiking southward toward Globe. The scouts successfully tracked the soldier. We apprehended him near the lower White River bridge, close to Tom Wanslee's trading store. In addition to those trips together, there were many other routine contacts at the fort. He, of course, did not handle the first sergeant's paperwork; that was done by white soldiers of the Quartermaster Detachment, but I always gave him the orders and other matters regarding the scouts for him to execute and pass along. He was a good leader, and a highly respected man at the fort.

During my tour of duty at Fort Apache in 1918.... old Billy was my favorite scout. He could speak only Apache and did not even understand pidgin-English. He lived by himself in a tin shack on the scout row just outside the east gate of the post proper. Frequently in the evenings when riding my mount around the post, I stopped at his place for a visit. We would squat on the ground, smoke hand-rolled cigarettes, and gaze at the evening sky without a word between us. When I got up to leave, it is my recollection that we always shook hands.

Upon retirement Charles Bones located in a little Indian settlement called Canyon Day, some four miles southwest of old Fort Apache. Here he opened a restaurant and served big meals for twenty-five cents. At that price many of the Indians ate there instead of purchasing more expensive food at the trader's store. Bones had a good trade but did not much more than break even. The old scout also kept a saddle horse and a good team. He exercised his horses by riding the saddle animal in front of the team hauling the wagon, using a lariat for a lead-line. By this method the old Apache was again in the saddle instead of jolting along on the wagon seat with the pony tied behind. Of course a stranger might wonder why the wagon was taken along, but Bones probably figured that was a method of keeping his team wagon-broke.

It is noted that the officer, who commanded the scouts in 1932, failed to have Sergeant Charles Bones advanced in grade upon retirement; such as was the custom of the old army in recognition of the long years faithful service. (80)

The separate units of Indian Scouts which had existed since 1866 were discontinued on June 30, 1921, and since that time the Apaches were carried on the Detached Enlisted Men's List.

Footnotes:

78. Shannon, James A., "With the Apache Scouts in Mexico," Journal of the U. S. Cavalry Association, April 1917.

79. Wharfield, Harold B., Apache Indian Scouts, published by the author, 1964, 22-3.

80. Wharfield, Harold B., 1964, 86, 91-2