Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993: Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

chuca Illustrat

ch uca

Illustrat

uca

Illustrat

Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca:

The Battle of Naco

chuca Illustrat

Rival factions in the northern provinces of Mexico maneuvered their armies so as to pin their enemies against the border. American forces positioned along that line would unwittingly be anchoring some rebel leader's flank and more than occasionally be caught in a crossfire.

John Francis Guilfoyle.

In early October 1914, entrenched rebel forces were besieged by Mexican

federal troops in the border town of Naco, Sonora.

In early October 1914, entrenched rebel forces were besieged by Mexican

federal troops in the border town of Naco, Sonora.

To protect the U.S. border, Colonel William C. Brown, leading four troops of the 10th Cavalry, arrived on the scene during the night of 7 October. He was joined by six troops and the machine gun platoon from the 9th Cavalry, under Colonel John Francis Guilfoyle who took overall command. Brown deployed west of the town while Guilfoyle took the eastern sector.

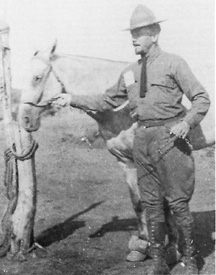

Captain Herman A. Sievert, Commanding Troop A,

9th Cavalry,

near Naco, Arizona, on the Mexican border in 1913.

On 17 October 1914, two Mexican factions, a pro-Obregon force under General Benjamin Hill and a pro-Villa army under General Maytorena, became locked in combat at Naco, Sonora. On the U. S. side of the border, in Naco, Arizona, the 9th and 10th Cavalry dug in to see that the Mexican forces did not cross the line and violate the U. S. neutrality.

From their trenches and rifle pits, the men of the 10th and their comrades from the 9th Cavalry watched the fighting. It was a dangerous business; the Buffalo Soldier regiment had eight men wounded while the Ninth "had some killed and wounded." They also lost a number of horses and mules from gunfire straying across the border.

It became a kind of deadly theater of the absurd. One observer noted that the men had "great difficulty ... in holding back the crowds of visitors from Bisbee and Douglas who flocked to see the 'battles,' in automobiles, wagons and horseback."

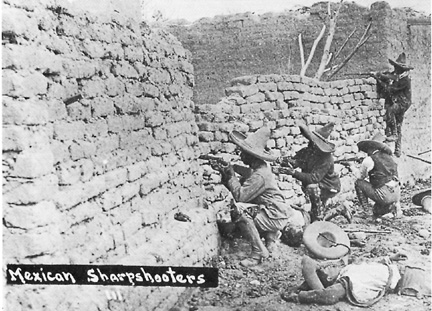

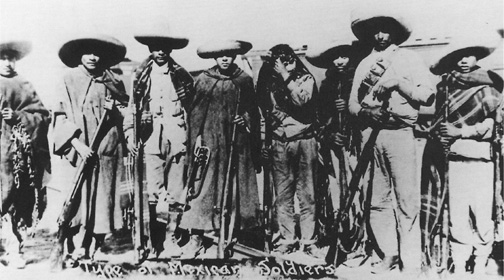

Rebel sharpshooters on the Mexican border. Photo courtesy

Col. James W. Fraser.

The men were under orders not to return fire, not an easy thing to do when the target for potshooters, and it was a tribute to the discipline of the regiment that they restrained themselves. For their "splendid conduct and efficient service" the men of the 10th were commended by the Secretary of War.

Brown later wrote of the affair:

... The Mexicans secured ammunition without limit from U.S. sources. ...The fire, with the exception of a truce from October 24 to November 9, was continuous until December 18, being heavier by night than by day, and included fire from small arms, three-inch shell, shrapnel, Hotchkiss revolving cannon, rockets, land mines, bombs, bugle calls and epithets! Eight men were wounded in the Tenth Cavalry and the regimental commander's tent hit four times. As the situation became more grave, additional troops were sent, and as Mexicans paid little attention to protests against their firing into U.S. camps, the latter were abandoned at night and eventually moved about a mile north of the line, along which outposts only, and these in bomb proofs, were maintained. The provocation to return the fire was very great, but so far as known not a shot was fired by the Tenth cavalry in retaliation.(39)

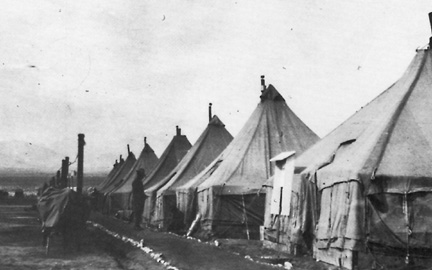

Tents of Troop D, 10th Cavalry, at Naco, Arizona, around 1914 or 15. This

troop was commanded by 1st Lieut. Orlando C. "Daddy" Troxel. Commanding

the First Squadron of the 10th Cavalry at Naco was Major Elwood Evans. Photo

courtesy Maj. Gen. John B. Brooks.

Colonel Frank Tompkins, chronicler of the Villa campaign, noted the discipline of the troopers.

This high state of discipline called forth a special letter of commendation from the President, and the Chief of Staff in his Annual Report for 1915.... referring to the conduct of the 9th and 10th Cavalry, said: "During the siege of Naco, Sonora, which was carried on for two and one-half months, the American troops at Naco, Arizona, were constantly on duty day and night to prevent the use of United States territory in violation of the neutrality laws. These troops were constantly under fire and one was killed and 18 were wounded without a single case of return fire of retaliation. This is the hardest kind of service and only troops in the highest state of discipline would stand such a test."(40)

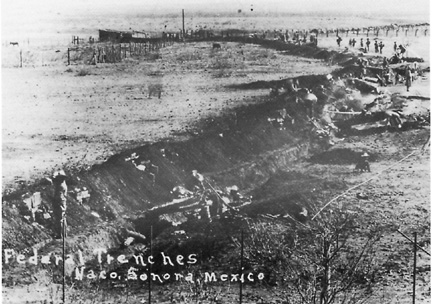

Federal trenches at Naco, Sonora, Mexico. National Archives photo.

Privately, Brown was mad at the danger his men were subjected to and critical of his orders not to take action. He wrote to a friend in October:

About 12:25 a.m., on the 17th [Maytorena] made the most determined attack yet made---first from the west, then from the east and lastly from the south, the direction which would send the high shots into our camp an of which he had previously been warned.

On the night of the 10th four shots hit the little R.R. station where I had my headquarters; on the night of the 16th-17th, 14 shots hit the same building and I should say that the shots (probably several hundred) dropped in our camp in about the same proportion.

Fortunately nearly all men and animals had been moved out for safety but notwithstanding this our casualty list was as follows: Four troopers wounded, one will probably die, and another lose his eye-sight. One horse and one mule killed one horse wounded besides at least two natives shot on the U.S. side of the line.

It is a surprise here that the U.S. takes no notice of such an outrageous proceeding.

Does the U.S. Government propose to sit complacently by and allow such deliberate firing perpendicular to the boundary that our soldiers are shot in their own camps? This after repeated warnings of the effect of such firing.

If this be true I am having my eyes opened, and getting an entirely new idea of the protection afforded by the U.S. flag.(41)

Mexican Sharpshooters. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo.

With the battle over, the regimental historian wrote, "the troops were given a rest and a chance to see what Huachuca looked like. Some of the men, after ten months' service on the border, had not yet seen their home station."(42)

The cavalrymen had a number of skirmishes with bandits during 1915. On 22 August, Troop K intercepted a band of Mexican soldiers who had crossed the border to rustle some cattle. The Troop K patrols drove them off with no losses to either side.

It was in November of that year that Pancho Villa's "northern division" was soundly defeated by President Carranza's government forces at Agua Prieta. Colonel William C. Brown, commanding the regiment, was there on 3 and 4 November with Troops B, E, G and M. The 10th Cavalry looked on from their blocking positions in Douglas, Arizona, and directed searchlights into the Mexican night, a move Pancho Villa considered as American support for his enemies.

The action during the month of November was especially hot. A 24-year-old private from Illinois named Harry J. Jones, Company C, 11th Infantry, was killed on 2 November 1915 by a stray bullet from the Mexican side of the line where the forces of Villa and Carranza were fighting. The U.S. Army camp at Douglas, Arizona, was named for him on 28 February 1916. Then, on 21 November, two privates were fired on by Mexicans while manning an observation post near Monument 117. The next day a camp of Troop F on the Santa Cruz River was fired upon by five armed Mexicans. The detachment returned the fire but there were no casualties reported. Another Troop F outpost on a hill near Mascarena's Ranch was hit on the 25th. In this raid, one Mexican was wounded and made prisoner.

"Type of Mexican Soldiers"

On 26 November 1915, a 30-minute firefight erupted in Nogales after Mexican soldiers fired at troops of the 12th Infantry on the American side of the border. Private Stephen D. Little, Company L, was killed along with an unknown number of Mexicans. The U.S. Army camp there was named for the 21-year-old South Carolinian on 18 December 1915. Meanwhile, on the western outskirts of Nogales, Carranza forces engaged in the siege of Nogales fired on Troop F, 10th Cavalry, who returned the fire, killing two of the Carranzistas and wounding others. Troop H was also being shot at during the siege of Nogales.(43)

Footnotes:

39. Brown papers in FHM files.

40. Tompkins, Frank, Chasing Villa, The Military Service Publishing Company, 1934, 37-8.

41. Brown papers in FHM files.

42. Glass, Edward L. N., History of the Tenth Cavalry, 1866-1921, Old Army Press, 1921, 64-5.