The Situation in Mexico

The Situation in Mexico

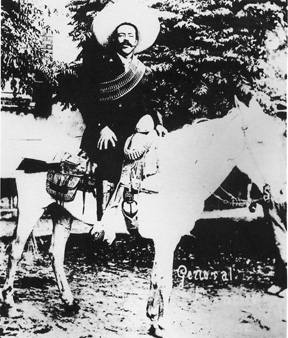

"Pancho" Francisco Villa on a white

mule.

"Pancho" Francisco Villa on a white

mule.

A chain of political events and armed revolution led to the ouster in May 1911 of long-time Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz. He was replaced by reformer Francisco Madero. In the months prior, Madero's supporters in Chihuahua had recruited to their cause a bandit and sometimes operator of a butcher shop in Chihuahua City. He was Doroteo Arango, who adopted the name of a deceased and legendary bandit with whom he is believed to have ridden, Francisco Villa.

Villa raised and led an army of revolutionaries in the state of Chihuahua and, along with the rebel army of Pascual Orozco, defeated the government rurales..

In March 1911, President William Howard Taft ordered the massing of 30,000 troops along the Mexican border, ostensibly for large-scale maneuvers. The assembled units were organized under the "Maneuver Division," on 12 March, and commanded by the champion of a general staff system within the U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. William Harding Carter. In August the Maneuver Division was disbanded and most of the units sent back to their original stations.

In 1912 the 9th Cavalry was sent to Douglas, Arizona, and the 13th Cavalry took up station at El Paso, Texas, to meet the increasing depredations by Mexican rebel forces and to enforce the neutrality laws. By the end of the year there were 6,754 soldiers along the line made up of 6 cavalry regiments, 1-1/2 infantry regiments, a battalion of field artillery, 2 companies of coast artillery and a signal corps company. During that summer, 67,280 militia troops joined the regulars on the border for five different joint maneuvers.

Madero's reign was not to be long-lived in the struggles for power that ensued. Gen. Victoriano Huerta, an often drunk but successful field commander, staged a coup which overthrew Madero in February 1913. Madero was arrested and killed. Madero's recently appointed Minister of War and Marine, Venustiano Carranza, emerged as the chief opponent of the new Huerta regime and his resistance was characterized as the "Constitutionalist" movement.

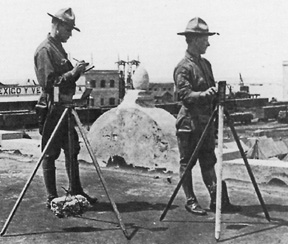

"Protecting Douglas." U.S. Army Signal Corps

photo.

Orozco, once a rebel leader fighting for Madero, now went over to Huerta

and combined his men with the federal forces fighting in Chihuahua. Because

of their insignia, they were known as the Colorados, or "Reds."

They terrorized the Chihuahua countryside.

Orozco, once a rebel leader fighting for Madero, now went over to Huerta

and combined his men with the federal forces fighting in Chihuahua. Because

of their insignia, they were known as the Colorados, or "Reds."

They terrorized the Chihuahua countryside.

Francisco "Pancho" Villa, allying himself with Carranza and the Constitutionalists, formed the opposition to Huerta in Chihuahua. His army had grown to 9,000 men and was known by the grand title of the Division del Norte.

A heliograph signalling station on the roof of the Terminal Hotel, Headquarters of the U.S. Expeditionary Forces, Vera Cruz, Mexico, 1914. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo.

In a bloody showdown on 23 June 1914 at Zacatecas, the Villistas decisively defeated the Huertistas and forced the 15 July resignation of Huerta and his exile. Federal forces lost between 5,000 and 8,000 killed and wounded, while the Constitutionalists suffered 4,000 casualties. It was the zenith of Villa's military career. Much of his military success was owed to his advisor, Brig. Gen. Felipe Angeles, a career professional who had recently returned from France. He had been sent out of the country by Huerta, who saw him as a threat to his own power and military prestige.

Brig. Gen. Tasker Bliss, commanding the Southern Department from Fort Sam Houston, Texas, gave the perspective from the American side of the line.

On February 15, 1913, the situation in Mexico along the international boundary was for the moment comparatively quiet. But with the overthrow of the Madero government and the establishment of the Federal authority under Huerta, it soon became evident that the States of Sonora and Coahuila would not accept the new government and active military operations were promptly inaugurated in both States against the Federal authority. This movement accepted Gov. Venustiano Carranza, of Coahuila, as its representative head and the faction styled itself Constitutionalists. The operations rapidly spread to the neighboring border States, and it soon became necessary to extend the border patrol on our side of the line so as to include the whole border from Brownsville, Tex., to Sasabe, Ariz. 30 miles west of Nogales, Ariz., a distance, following the windings of the frontier, of some 1.600 miles.

* * * * * *

There then followed a series of contests for possession of the border towns, some of which resulted in fighting on the boundary line.

On March 13 the rebels under Obregon attacked Nogales, Sonora, in force. The Federal defending forces composed of regular Federal troops under Reyes, and a force of gendarmeria fiscales, formerly rurales, under Kosterlitsky, were defeated and crossed the line to the American side of boundary and surrendered to our troops.

The American troops on our side of the line consisted of two mounted and three dismounted troops, Fifth Cavalry, under command of Col. Tate, and later under Col. Wilder. A number of shots fell on the American side, and one soldier of Troop G, Fifth Cavalry, was wounded, a bullet passing through nose and cheek. One Mexican boy, herding cows outside of town on the American side, was wounded.

The shots which came on the American side were accidental and apparently unavoidable in case of a fight between the contending forces actually on the boundary line.

Gen. Ojeda, in command of the Mexican Federal troops in Sonora, was in Agua Prieta early in March with a force of about 500 men, composed of Yaqui Indians and regular troops. The opposing rebel forces were assembling for an attack on the town, but on March 12 Ojeda evacuated Agua Prieta and moved to Naco, Sonora. The rebel troops occupied Agua Prieta the same day without opposition.

From Naco as a base, Ojeda operated for a month against the rebel forces assembling to attack him. He moved out of town and on two occasions attacked and defeated rebel columns advancing to attack him on March 15 and 20.

On March 17 the Yaqui Indians in his command to the number of 110 men with 32 women deserted and came across to the American side of the boundary and surrendered to our troops. Others deserted in the following few days until the total number of Yaquis reached 213.

Ojeda continued his defense of Naco with about 300 men, when he was attacked by rebels under Obregon on April 8. The fighting continued with aggressive return by Ojeda on the 10th, but finally the rebel attack assumed such proportions on the 13th that Ojeda was defeated and with his remaining troops crossed the boundary line and surrendered to our troops.

Col. Guilfoyle, with headquarters, machine-gun platoon, and Troops E, F, I, K, L, and M, of the Ninth Cavalry, was in charge of our forces. A number of shots fell on the American side in the town of Douglas, Ariz., and in the camp of the Ninth Cavalry during the fighting. Three soldiers and three animals of the Ninth Cavalry were wounded in the fight of the 8th.

In accordance with instructions from the War Department, Col. Guilfoyle notified the commanders of both sides in advance of the fighting that they must not direct their fire so that bullets should come across the line. The rebel commander in return gave assurance that he would do all he could to prevent shots from falling on the American side.

In addition to the Yaqui Indians and Federals, a number of rebels crossed the line at different periods and the wounded of both parties were brought to the American side of the boundary, where they were cared for by our medical officers.

* * * * * *

At Nogales, Ariz., after the capture of Nogales, Sonora, by the revolutionists on March 13, there surrendered to our troops: Mexican Federal officers 2, Mexican Federal men 101, of whom 1 officer and 43 men were of the regular troops and the remainder belonged to the gendarmeria fiscales.

At Naco, Ariz., between March 17 and April 13, there surrendered: Mexican Federals, wounded, 8 officers, 48 men; Mexican Federals, unwounded, 28 officers, 260 men; Yaqui Indians (deserters from Mexican Federal force), 213 men; rebels, wounded, 2 officers, 28 men. These Yaqui Indians were accompanied by a large number of women and children. [On April 18 the prisoners were released and allowed to filter back across the line.](33)

-----------

-----------

Frederick Funston.---------------------------------------------

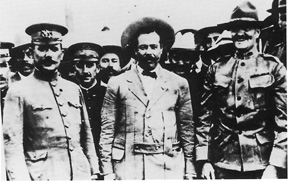

From left to right: General Alvaro Obregon,

U.S. Army Signal Corps photo.----------------------------------- Pancho Villa, Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing.

Villa's success in Chihuahua was paralleled by another amateur general in the state of Sonora. He was a former school teacher named Alvaro Obregon, a descendent of the O'Briens who had served in the Spanish Army in Mexico. Obregon soundly beat the federal troops, led by Col. Emilio Kosterlitzky, at Nogales on 13 March 1913 and followed up his win with victories at Cananea on 26 March, at Santa Rosa on 13 May, and at San Alejandro on 27 June.

General Carranza with General Ortega, undated. Photo

courtesy Col. James W. Fraser.

American sailors were arrested in Tampico, Mexico, by an increasingly hostile Mexican government. In April a landing force of 8,000 marines and soldiers led by Army Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston occupied Vera Cruz but were withdrawn when Mexican president Huerta resigned. To the soldiers along the border, the situation looked grave and many thought war with Mexico was inevitable. At Huachuca Lieutenant Jerome Howe entered in his diary on 18 April 1914, "Mexican situation pretty acute." Two days later, he wrote, "Huerta has not complied with U.S. demands for apology. Looks like intervention." On 22 April he exclaimed, "Vera Cruz taken!" By the 28th he thought "War apparently unavoidable." He was taking his K Troop to the range everyday to sharpen the marksmanship skills of his newer troops. A month later found him with his troop taking up station at Naco.(34)

The U.S.

Army on the Mexican Border, 1910-1930.

The U.S.

Army on the Mexican Border, 1910-1930.

Villa and Obregon inevitably clashed over political or territorial differences and in late August 1914 they held negotiations at El Paso, Texas, a meeting at which Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing was present.

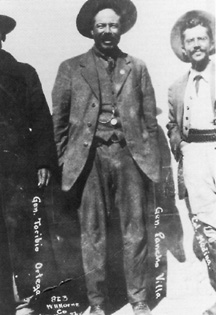

General Fierro, General Francisco "Pancho" Villa, and Brig. Gen.

Hugh Lenox Scott, leave a conference.

A photo by W.H. Horne Co., El Paso, Texas. Photo courtesy Col. James W.

Fraser.

In the scramble for power that followed Huerta's deportation, several

leaders vied for preeminence. The best known were Villa, Carranza, Obregon,

and Zapata. Mexico found itself at one point with four governments and the

capital changing hands sometimes daily. But Carranza and Obregon, status-conscious

educated Creoles, wanted to dump Villa and Zapata, who were largely illiterate

peasants and represented peasant interests.

In the scramble for power that followed Huerta's deportation, several

leaders vied for preeminence. The best known were Villa, Carranza, Obregon,

and Zapata. Mexico found itself at one point with four governments and the

capital changing hands sometimes daily. But Carranza and Obregon, status-conscious

educated Creoles, wanted to dump Villa and Zapata, who were largely illiterate

peasants and represented peasant interests.

General Pancho Villa with Gen. Toribio Ortega and Col. Medina.

The organizational talents of Carranza and Obregon were too powerful for Villa. His forces suffered one set back after another in 1915. Carranza forces pushed his Division del Norte northward until finally his back was against the United States line. At Agua Prieta, opposite Douglas, Arizona, Villa engaged Carranzistas under Gen. Plutarco Elias Callas on 1 November 1915. His army was wrecked in this battle in which enemy reinforcements caught him from the rear. Carranza and Obregon branded him an outlaw. So, the man who had begun his adult life as a brigand, and was transformed into a revolutionary general, now found himself once again a bandit. With what was left of his army, he sought refuge in the mountains of Chihuahua to carry on his fight as a guerilla. Once strongly pro-American, Villa now bitterly detested theYanquis for their official recognition of the Carranza government. Members of his band hit a train in Chihuahua and murdered sixteen American miners and engineers whom they found aboard. And, on 9 March 1916, Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico, killing twenty-six Americans, an act which prompted a Punitive Expedition led by Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing.

Carranza was assassinated on 21 May 1920, and his government overthrown. His successor, Adolfo de la Huerta, made peace with Villa in 1920 and gave him a large ranch upon which to retire with his followers. Villa was assassinated in an ambush outside Parral on 23 July 1923. (35)

Footnotes:

33. Annual Report of the Southern Department, fiscal year 1913.

34. Howe, Jerome, diary page in letter to John B. Brooks, on file in Fort Huachuca Museum archives.

35.Tuck, Jim, Pancho Villa and John Reed: Two Faces of Romantic Revolution, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1984.