"Light of heart and much enduring,

Straight and debonair and dauntless . . ." |

Major Owen Rutter (1889-1944) |

Poets of the Great War

On November 11, 1985 (the 67th anniversary of the Armistice), a slate stone was unveiled in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey commemorating 16 Great War poets:

All 16 poets whose names appear on the memorial served in uniform during the war. At 45, Binyon was the oldest at the start of the war. Blunden the youngest, at 18. Of the 16 poets, Brooke, Grenfell, Owen, Rosenberg, Sorley, and Thomas died in the war. The only poet of the group still alive at the unveiling in 1985 of the stone in Westminster Abbey was Robert Graves, who died later that same year. The inscription on the stone is from Owen's now-famous "Preface" to his poems: All 16 poets whose names appear on the memorial served in uniform during the war. At 45, Binyon was the oldest at the start of the war. Blunden the youngest, at 18. Of the 16 poets, Brooke, Grenfell, Owen, Rosenberg, Sorley, and Thomas died in the war. The only poet of the group still alive at the unveiling in 1985 of the stone in Westminster Abbey was Robert Graves, who died later that same year. The inscription on the stone is from Owen's now-famous "Preface" to his poems:

"My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

(Thanks to Penny Neary, Concert Secretary at Westminster Abbey)

Richard Aldington Richard Aldington

1892-1962

.jpg) War and Love (1915-1918) by Richard Aldington. -- Boston, The Four seas company, 1919. War and Love (1915-1918) by Richard Aldington. -- Boston, The Four seas company, 1919.

Richard Aldington (1892-1962) served on the Western Front from 1916-1918, and published his war poetry in War and Love (1915-1918). -- Boston, The Four Seas Company, 1919. Aldington is primarily remembered as the author of the novel Death of a Hero (1929) -- and for his later literary bickering with such fellow Great War veterans as Robert Graves and B.H. Liddell Hart over the popular memory of T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia), another legendary Great War veteran. A poet in the Imagist school, Aldington married the American poet Hilda Doolittle (H. D.) in 1913. Aldington was also a "Vorticist," and a signatory of the "Manifesto" printed in BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex.

Laurence Binyon Laurence Binyon

1869-1943

.jpg) The Winnowing Fan: Poems on The Great War, by Laurence Binyon. -- London, E. Mathews, 1915. The Winnowing Fan: Poems on The Great War, by Laurence Binyon. -- London, E. Mathews, 1915.

The oldest of the war poets (he was 45 when the war began), Laurence Binyon (1869-1943) was an expert on Oriental art at the British Museum, and an established scholar and poet. Binyon's best remembered poem from the Great War, "For the Fallen," is still quoted at RAF funerals.

.jpg) .jpg) Edmund Blunden Edmund Blunden

1896-1974

Pastorals : a Book of Verses / by E.C. Blunden. -- London : E. Macdonald, <1916> (The little books of Georgian verse (second series) under the general editorship of S. Gertrude Ford )

.gif) The youngest of the war poets (he was 18 when the war started), Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) went to school at Christ's Church, and wrote artful pastoral poetry. After the war, Blunden was a professor in Tokyo and Hong Kong. His memoirs, Undertones of War (1928) -- typcially understated, and filtered through his gentle pastoralism -- rank with Goodbye to All That (1929) by Robert Graves, and The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston (1928, 1930, 1936) by Seigfried Sassoon "as among the finest prose works by a Great War poet" (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 331). A close friend of Siegfried Sassoon (who had helped promote his literary career), Blunden later edited and helped bring to light the work of Wilfred Owen and Ivor Gurney. Blunden also discovered and brought to light John Clare's hitherto unpublished work (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 332). Many years later, Blunden was, ironically, also an English tutor to Keith Douglas at Merton College. Douglas, who was later killed in combat following the Normandy (D-Day) Landing in 1944, is considered to be the greatest poet of the Second World War. Blunden's celebratory poem "At Senlis Once" -- published in the volume The Midnight Skaters (1968) -- has sometimes been thought by casual readers to refer to the Armistice. The youngest of the war poets (he was 18 when the war started), Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) went to school at Christ's Church, and wrote artful pastoral poetry. After the war, Blunden was a professor in Tokyo and Hong Kong. His memoirs, Undertones of War (1928) -- typcially understated, and filtered through his gentle pastoralism -- rank with Goodbye to All That (1929) by Robert Graves, and The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston (1928, 1930, 1936) by Seigfried Sassoon "as among the finest prose works by a Great War poet" (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 331). A close friend of Siegfried Sassoon (who had helped promote his literary career), Blunden later edited and helped bring to light the work of Wilfred Owen and Ivor Gurney. Blunden also discovered and brought to light John Clare's hitherto unpublished work (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 332). Many years later, Blunden was, ironically, also an English tutor to Keith Douglas at Merton College. Douglas, who was later killed in combat following the Normandy (D-Day) Landing in 1944, is considered to be the greatest poet of the Second World War. Blunden's celebratory poem "At Senlis Once" -- published in the volume The Midnight Skaters (1968) -- has sometimes been thought by casual readers to refer to the Armistice.

.jpg) The Midnight Skaters <by> Edmund Blunden. Poems for young readers chosen and introduced by C. Day Lewis; illustrations by David Gentleman. -- London, Sydney <etc.> Bodley Head, 1968. The Midnight Skaters <by> Edmund Blunden. Poems for young readers chosen and introduced by C. Day Lewis; illustrations by David Gentleman. -- London, Sydney <etc.> Bodley Head, 1968.

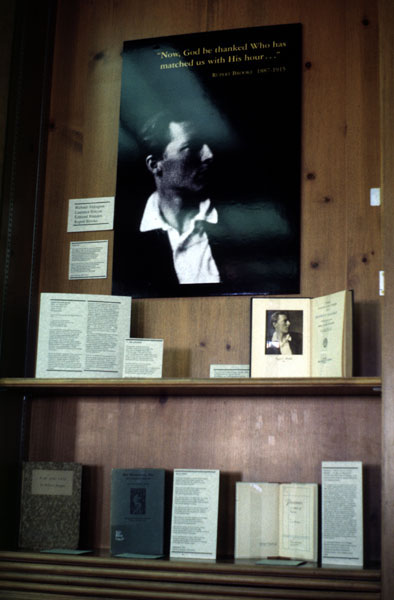

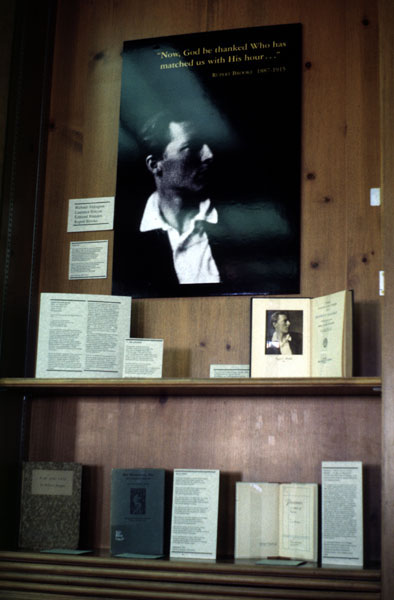

.jpg) Rupert Chawner Brooke Rupert Chawner Brooke

Born: 3rd August 1887

Died: 23rd April 1915

Aged: 28 years

Sub-Lieutenant

Yeats called Brooke "the handsomest young man in England." Another admirer, Henry James, introduced Brooke's Letters from America (1916). Born and educated at Rugby, Rupert Brooke glittered as he walked with friends such as E. M. Forster, and Virginia Woolf (with whom he also went skinny-dipping; while for her part, Woolf thought Brooke would someday be Prime Minster). However, Brooke's personal life was troubled with bouts of depression, and nervous breakdowns, usually occasioned by his disastrous (attempts at) relationships with women. Yeats called Brooke "the handsomest young man in England." Another admirer, Henry James, introduced Brooke's Letters from America (1916). Born and educated at Rugby, Rupert Brooke glittered as he walked with friends such as E. M. Forster, and Virginia Woolf (with whom he also went skinny-dipping; while for her part, Woolf thought Brooke would someday be Prime Minster). However, Brooke's personal life was troubled with bouts of depression, and nervous breakdowns, usually occasioned by his disastrous (attempts at) relationships with women.

.jpg) Brooke was awarded a commission in the Royal Naval Division (personally organized by then Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill), he participated in the evacuation of Antwerp, Belgium in October 1914, wrote his soon-to-be famous sonnets entitled "1914" over Christmas, and early in 1915 was enroute with his battalion (which also included the Prime Minster's son, Arthur Asquith) to take part in Churchill's Dardenelles campaign. Meanwhile, back in England, to bolster the nation and inspire the youth, Dean Inge of St. Paul's read Brooke's sonnet "V. The Soldier" from the pulpit on Easter Sunday. However, already weakened by sunstroke, Brooke contracted blood poisoning from a mosquito bite on his lip, and two days before the landings at Gallipoli, on April 23rd (coincidentally, St. George's Day, and the traditional birthday of Shakespeare), Rupert Brooke died. He died in the Agean, was buried on the Island of Skyros, and his obituary in The Times was written by Churchill, himself. When he heard of Brooke's death, D. H. Lawrence wrote "he was slain by bright Pheobus' shaft . . . it was a real climax of his pose . . . bright Pheobus smote him down. It is all in the saga. O God, O God; it is all too much a piece: it is like madness." (See also Rupert Brooke's death and burial : based on the log of the French hospital ship Duguay-Trouin / translated from the French of J. Perdriel-Vaissières by Vincent O'Sullivan (1917).) Brooke was awarded a commission in the Royal Naval Division (personally organized by then Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill), he participated in the evacuation of Antwerp, Belgium in October 1914, wrote his soon-to-be famous sonnets entitled "1914" over Christmas, and early in 1915 was enroute with his battalion (which also included the Prime Minster's son, Arthur Asquith) to take part in Churchill's Dardenelles campaign. Meanwhile, back in England, to bolster the nation and inspire the youth, Dean Inge of St. Paul's read Brooke's sonnet "V. The Soldier" from the pulpit on Easter Sunday. However, already weakened by sunstroke, Brooke contracted blood poisoning from a mosquito bite on his lip, and two days before the landings at Gallipoli, on April 23rd (coincidentally, St. George's Day, and the traditional birthday of Shakespeare), Rupert Brooke died. He died in the Agean, was buried on the Island of Skyros, and his obituary in The Times was written by Churchill, himself. When he heard of Brooke's death, D. H. Lawrence wrote "he was slain by bright Pheobus' shaft . . . it was a real climax of his pose . . . bright Pheobus smote him down. It is all in the saga. O God, O God; it is all too much a piece: it is like madness." (See also Rupert Brooke's death and burial : based on the log of the French hospital ship Duguay-Trouin / translated from the French of J. Perdriel-Vaissières by Vincent O'Sullivan (1917).)

Before the war Brooke had collaborated with (then better known poet) Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie, and John Dinkwater on a publication entitled New Numbers. Brooke's "1914" sonnets were first published in New Numbers. Foreshadowing the innocent Ringo-for- Pete Best exchange, Brooke named Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie, and Walter de la Mare (rather than Drinkwater) as his heirs, unintentionally dooming all three to a lifetime of financial independence. Before the war Brooke had collaborated with (then better known poet) Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie, and John Dinkwater on a publication entitled New Numbers. Brooke's "1914" sonnets were first published in New Numbers. Foreshadowing the innocent Ringo-for- Pete Best exchange, Brooke named Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie, and Walter de la Mare (rather than Drinkwater) as his heirs, unintentionally dooming all three to a lifetime of financial independence.

"Until the cult of Wilfred Owen sprang up in the last quarter of the twentieth century, Brooke was the icon of the First World War" (Holt 34). Now, after suffering through a long period of negative opinion, Brooke's reputation is enjoying something of a comeback -- especially when his work is considered in its historical, essentially pre-war context. (For more on the life and works of Rupert Brooke, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/brooke/.)

.jpg) Wilfrid Wilson Gibson Wilfrid Wilson Gibson

1878-1962

.gif) Battle, and Other Poems / by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson ... -- New York, The Macmillan Company, 1916. Battle, and Other Poems / by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson ... -- New York, The Macmillan Company, 1916.

.jpg) Wilfrid Gibson (1878-1962) was a well-known poet before the war. Friend of Edward Thomas and Robert Frost. Collaborator with Rupert Brooke on New Numbers : A Quarterly Publication of the Poems of Rupert Brooke, John Drinkwater, Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie. Gibson's sincerity in his relationship with Rupert Brooke (who called him "Wibson") is evident in his poem about Brooke entitled "The Going." Gibson is also one of the few war poets (most of whom were young and single) to write from the perspective of an older man, married with children (Stephen, The Price of Pity 185). Gibson's poem "A Lament" speaks to the war's survivors. Wilfrid Gibson (1878-1962) was a well-known poet before the war. Friend of Edward Thomas and Robert Frost. Collaborator with Rupert Brooke on New Numbers : A Quarterly Publication of the Poems of Rupert Brooke, John Drinkwater, Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Lascelles Abercrombie. Gibson's sincerity in his relationship with Rupert Brooke (who called him "Wibson") is evident in his poem about Brooke entitled "The Going." Gibson is also one of the few war poets (most of whom were young and single) to write from the perspective of an older man, married with children (Stephen, The Price of Pity 185). Gibson's poem "A Lament" speaks to the war's survivors.

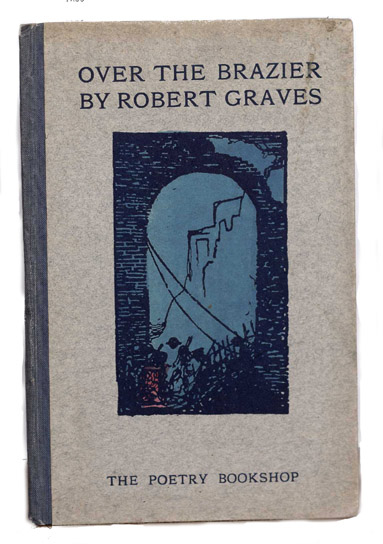

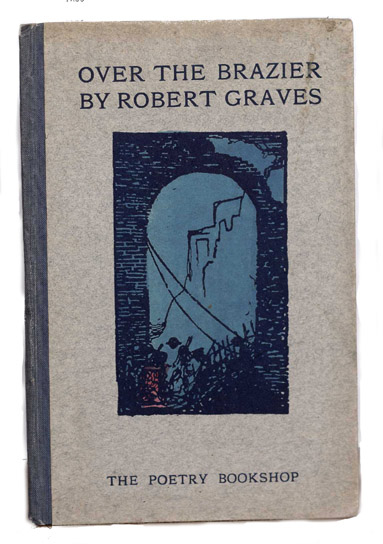

Robert Graves Robert Graves

1895-1985

.jpg) Robert Graves was commissioned in the Royal Welch Fusiliers in August 1914. He participated in the Battle of Loos (1915) -- where Charles Sorley was killed -- and was wounded during the Battle of the Somme (1916), and reported dead. Graves met Siegfried Sassoon while both were serving as officers in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. And while visiting Sassoon at Craiglockhart Hospital, Graves also met Wilfred Owen. A prolific writer throughout his long life, Robert Graves published three volumes of poetry during the war, Over the Brazier (1916) Goliath and David (1916), and Fairies and Fusiliers (1917) -- which includes the poem "Sorley's Weather" -- and several volumes afterwards (click here to see more volumes of Robert Graves' poetry held by the Lee Library). (Also, click here to see a fanciful comparison of the "war poetry" of Robert Graves and American Edgar A. Guest.) Robert Graves was commissioned in the Royal Welch Fusiliers in August 1914. He participated in the Battle of Loos (1915) -- where Charles Sorley was killed -- and was wounded during the Battle of the Somme (1916), and reported dead. Graves met Siegfried Sassoon while both were serving as officers in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. And while visiting Sassoon at Craiglockhart Hospital, Graves also met Wilfred Owen. A prolific writer throughout his long life, Robert Graves published three volumes of poetry during the war, Over the Brazier (1916) Goliath and David (1916), and Fairies and Fusiliers (1917) -- which includes the poem "Sorley's Weather" -- and several volumes afterwards (click here to see more volumes of Robert Graves' poetry held by the Lee Library). (Also, click here to see a fanciful comparison of the "war poetry" of Robert Graves and American Edgar A. Guest.)

But Graves is probably best remembered for his "autobiography" Goodbye to All That (1929), which earned enough to provide him a happy self-exile in Majorca. And true to his Goodbye, But Graves is probably best remembered for his "autobiography" Goodbye to All That (1929), which earned enough to provide him a happy self-exile in Majorca. And true to his Goodbye, .jpg) Graves also later excised much of his war poetry from his collected works, something which subsequent anthologists have respected. Today, Graves is also remembered by many as the author of a biography of T.E. Lawrence (see Aldington), the quasi-historical novel I Claudius, and his own poetical philosophy contained in The White Goddess. However, this is much evidence that Graves remained a Royal Welch Fusilier to the end, true to his poem "Retrospect: The Jests of The Clock" (an ironic inverse of his earlier poem, "Big Words"), and somewhat like the subject of his own poem "The Patchwork Quilt." At the outbreak of the Second World War, Graves tried to enlist, but was turned down (unfortunately, it was Graves' son David, instead, who went to war and was killed in 1943 fighting the Japanese on the subcontinent . . . ironically Graves' title poem from Goliath and David (1916) told of a young David -- actually David Thomas, a close friend of Graves and Sassoon who was killed in the Great War -- who loses his duel with Goliath). Graves also later excised much of his war poetry from his collected works, something which subsequent anthologists have respected. Today, Graves is also remembered by many as the author of a biography of T.E. Lawrence (see Aldington), the quasi-historical novel I Claudius, and his own poetical philosophy contained in The White Goddess. However, this is much evidence that Graves remained a Royal Welch Fusilier to the end, true to his poem "Retrospect: The Jests of The Clock" (an ironic inverse of his earlier poem, "Big Words"), and somewhat like the subject of his own poem "The Patchwork Quilt." At the outbreak of the Second World War, Graves tried to enlist, but was turned down (unfortunately, it was Graves' son David, instead, who went to war and was killed in 1943 fighting the Japanese on the subcontinent . . . ironically Graves' title poem from Goliath and David (1916) told of a young David -- actually David Thomas, a close friend of Graves and Sassoon who was killed in the Great War -- who loses his duel with Goliath).

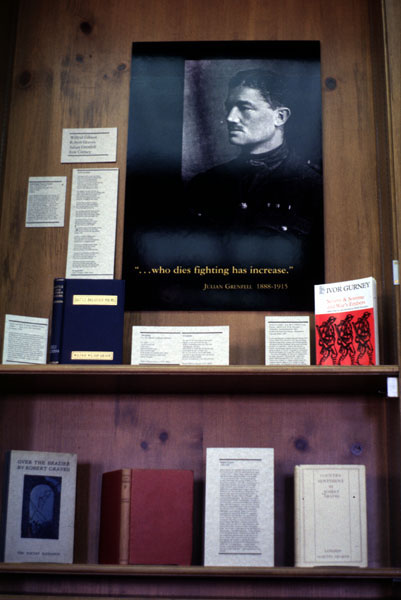

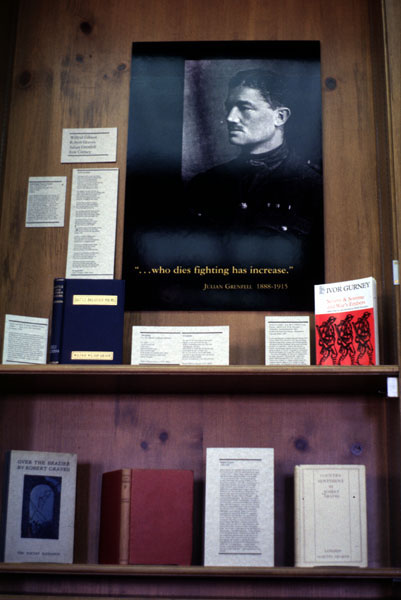

.gif) Julian Henry Francis Grenfell Julian Henry Francis Grenfell

Born: 30th March 1888

Died of Wounds: 26th May 1915

Aged 27 years

Captain

From a family of military men, Julian Grenfell was already an officer in the regular army when the war started. A boxer and cavalryman who liked to stalk enemy snipers, Grenfell did not mince words. He wrote to his family "I adore war. It's like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic. I have never been so well or so happy . . . Here we are in the burning centre of it all, and I would not be anywhere else for a million pounds and the Queen of Sheba." Grenfell wrote his most famous war poem, "Into Battle," on April 29th, 1915. It was published in The Times in May of 1915. On the 13th of May, Grenfell was hit in the head by a shell fragment near Ypres, and died on May 26, 1915. (Grenfell's younger brother, Billie, was also killed in the war.) From a family of military men, Julian Grenfell was already an officer in the regular army when the war started. A boxer and cavalryman who liked to stalk enemy snipers, Grenfell did not mince words. He wrote to his family "I adore war. It's like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic. I have never been so well or so happy . . . Here we are in the burning centre of it all, and I would not be anywhere else for a million pounds and the Queen of Sheba." Grenfell wrote his most famous war poem, "Into Battle," on April 29th, 1915. It was published in The Times in May of 1915. On the 13th of May, Grenfell was hit in the head by a shell fragment near Ypres, and died on May 26, 1915. (Grenfell's younger brother, Billie, was also killed in the war.)

.gif) Ivor Gurney Ivor Gurney

Born: 28 August 1890

Died: 26 December 1937

Aged 47 years

Private

Severn & Somme ; and, War's Embers / Ivor Gurney ; edited by R. K. R. Thornton. -- Ashington, Northumberland : Mid Northumberland Arts Group ; Manchester : Carcanet Press, 1997.

.jpg) A poet and musician, a friend of Edward Thomas, Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) enlisted in 1915 after first being rejected because of his eyesight. After being wounded and gassed, he was discharged, but he never recovered from his war experience -- indeed, after the war, Gurney was tormented with the idea that it was still going on. Much of Gurney's war poetry is contained in Severn and Somme (1917), and War's Embers (1919) -- the much anthologized "To His Love" coming from the latter. The poem "The Silent One" comes from poems written between 1919-1922. In 1922, Ivor Gurney was confined to a mental hospital, where he remained until his death in 1937. Gurney set many works to music, including poems by Edward Thomas and Rupert Brooke. Edmund Blunden later edited two volumes of his work, doing much to bring Gurney's talent and work to light. A poet and musician, a friend of Edward Thomas, Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) enlisted in 1915 after first being rejected because of his eyesight. After being wounded and gassed, he was discharged, but he never recovered from his war experience -- indeed, after the war, Gurney was tormented with the idea that it was still going on. Much of Gurney's war poetry is contained in Severn and Somme (1917), and War's Embers (1919) -- the much anthologized "To His Love" coming from the latter. The poem "The Silent One" comes from poems written between 1919-1922. In 1922, Ivor Gurney was confined to a mental hospital, where he remained until his death in 1937. Gurney set many works to music, including poems by Edward Thomas and Rupert Brooke. Edmund Blunden later edited two volumes of his work, doing much to bring Gurney's talent and work to light.

David Jones

1895-1974

Paul Fussell describes David Jones as "that odd, unassignable modern genius, half-English, half-Welsh, at once painter, poet, essayist, and engraver, a prodigy of folklore and liturgy and an adept at myth, ritual, and romance, the turgid allusionist of In Parenthesis" (The Great War and Modern Memory, 144). Jones enlisted in January 1915, served as a private, and was wounded during the Battle of the Somme. He also later served at Ypres. W. H. Auden described Jones' epic work In Parenthesis (1937), as "[not] a war book so much as a distillation of the essence of war books." In Parenthesis is part prose, part poem, rich in allegory, often idiosyncratic and obscure, as it tells the tale of the protagonist John Ball and his unit from December 1915 to the July 1, 1916. Ball and his unit ship out to France, move up and occupy trenches, pull duty, and finally participate in the Battle of the Somme, where Ball is wounded. (See also English Poetry of the First World War; a Study in the Evolution of Lyric and Narrative Form / by John H. Johnston. - Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1964. -- the first full-length study of Great War poetry, and an early champion of David Jones' epic In Parenthesis.)

Robert Nichols Robert Nichols

1893-1944

Ardours and Endurances ; Also, A Faun's Holiday & Poems & Phantasies / by Robert Nichols. -- New York, Frederick A. Stokes company <1918>

A Georgian poet, friend of Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Nichols (1893-1944) served for a short time at the front (including the Battle of the Somme) as an artillery officer, then was invalided home suffering from shell-shock. Nichols then went on to become a famous "soldier poet" during the war, touring the United States giving readings of his, and others' poems. Nichols' most famous collection of war poetry: Ardours and Endurances (1917), aims at a thematic effect -- that is, to tell the epic story of the war -- through the organization of the individual poems in the collection into sections entitled "The Summons," "Farewell to Place of Comfort," "The Approach," "Battle," "The Dead," "The Aftermath." (For more about portraying the war through epic poetry, see David Jones and In Parenthesis, Herbert Read and The End of a War, and John H. Johnston and English Poetry of the First World War; a Study in the Evolution of Lyric and Narrative Form.)

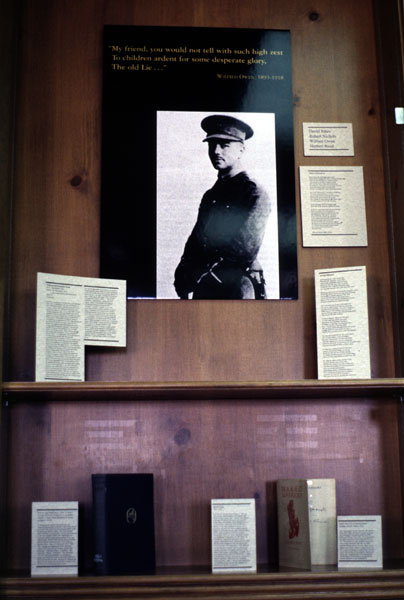

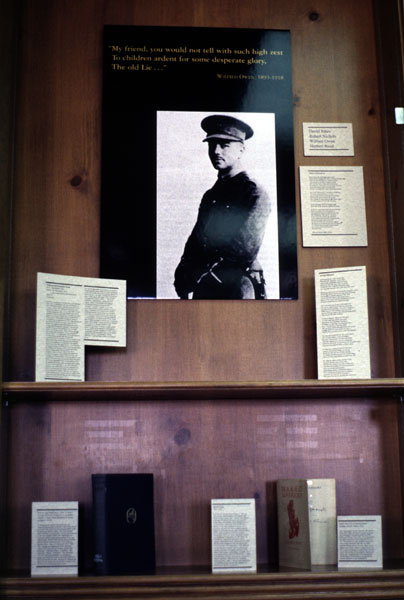

.gif) Wilfred Edward Salter Owen Wilfred Edward Salter Owen

Born: 18th March 1893

Killed: 4th November 1918 (one week before the Armistice)

Aged 25

Lieutenant

Arguably the greatest of the Great War poets, Wilfred Owen was "A Shropshire Lad" born in Oswestry, in 1893. Dedicated to poesy, devoted to and influenced by Keats, Owen's self-training as a Romantic poet carried over and flavored even his war poems (in spite of being claimed by critics as a Modern poet, Owen remained to the last a Georgian). When the war began, Owen was in France, English tutor to a prominent French family. He returned to England, enlisted in 1915, and was commissioned in 1916. After serving on the Western Front from January to June of 1917, Owen was diagnosed with shell-shock, and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon who introduced him to Robert Nichols and Robert Graves. When Sassoon showed Graves the poem "Disabled," Graves pronounced Owen "a find." At Craiglockhart, Owen and Sassoon became friends, and the older Sassoon had considerable effect on Owen as the two compared and edited each others' poetry (Sassoon also introduced Owen to his publishing connections). (See Stephen MacDonald's play Not About Heroes : the Friendship of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen for more about the meeting and friendship of Sassoon and Owen while at Craiglockhart.) Craiglockhart was a productive time for Owen, while at the hospital he wrote such poems as "Dulce et Decorum Est" and "Anthem for Doomed Youth." Reinvigorated by a new sense of himself as poet and soldier, Owen returned to the front in September 1918, won the Military Cross for gallantry in October, and was killed while leading his men on November 4th -- one week before the Armistice (the church bells had been pealing for an hour in celebration on November 11th when word finally reached his family). After the war, Siegfried Sassoon gathered and published Owen's poems (1920). Some years later, Edmund Blunden also edited a larger collection of Owen's poetry (1931). Arguably the greatest of the Great War poets, Wilfred Owen was "A Shropshire Lad" born in Oswestry, in 1893. Dedicated to poesy, devoted to and influenced by Keats, Owen's self-training as a Romantic poet carried over and flavored even his war poems (in spite of being claimed by critics as a Modern poet, Owen remained to the last a Georgian). When the war began, Owen was in France, English tutor to a prominent French family. He returned to England, enlisted in 1915, and was commissioned in 1916. After serving on the Western Front from January to June of 1917, Owen was diagnosed with shell-shock, and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon who introduced him to Robert Nichols and Robert Graves. When Sassoon showed Graves the poem "Disabled," Graves pronounced Owen "a find." At Craiglockhart, Owen and Sassoon became friends, and the older Sassoon had considerable effect on Owen as the two compared and edited each others' poetry (Sassoon also introduced Owen to his publishing connections). (See Stephen MacDonald's play Not About Heroes : the Friendship of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen for more about the meeting and friendship of Sassoon and Owen while at Craiglockhart.) Craiglockhart was a productive time for Owen, while at the hospital he wrote such poems as "Dulce et Decorum Est" and "Anthem for Doomed Youth." Reinvigorated by a new sense of himself as poet and soldier, Owen returned to the front in September 1918, won the Military Cross for gallantry in October, and was killed while leading his men on November 4th -- one week before the Armistice (the church bells had been pealing for an hour in celebration on November 11th when word finally reached his family). After the war, Siegfried Sassoon gathered and published Owen's poems (1920). Some years later, Edmund Blunden also edited a larger collection of Owen's poetry (1931).

.jpg) It would be impossible in this sketch to do justice to Owen's greatest poems. However, three (in addition to the ones already mentioned) provide a glimpse at Owen's progress as a poet: "Apologia Pro Poemate Meo" ("Apology for My Poetry") traces Owen's education from child to soldier -- with all the experience, understanding, and pity that that title implies. There's "Strange Meeting" (perhaps influenced by Siegfried Sassoon's poem "Enemies"), loved by "modern" critics, who considered it Owen's greatest poem for its use of near, or pararhyme (something Owen probably picked up from his time in France as an English tutor), and for its scenes of cold, dark, lonely hell -- a foreshadow of the entire post-war wasteland (including Eliot's actual The Waste Land (1922)). Owen does something similar to what he does in these two poems, but in prose, in what was to be his "Preface" to his poems. In "Spring Offensive" (also considered by some to be Owen's greatest poem) Owen's traditional Romanticism with Romantic descriptions of nature, experience in 20th Century existentialist hell, and genuine pity for his fellows all come together. Coincidentally, "Spring Offensive" is also probably Owen's last complete poem. (For more on the life and works of Wilfred Owen, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/owen/.) It would be impossible in this sketch to do justice to Owen's greatest poems. However, three (in addition to the ones already mentioned) provide a glimpse at Owen's progress as a poet: "Apologia Pro Poemate Meo" ("Apology for My Poetry") traces Owen's education from child to soldier -- with all the experience, understanding, and pity that that title implies. There's "Strange Meeting" (perhaps influenced by Siegfried Sassoon's poem "Enemies"), loved by "modern" critics, who considered it Owen's greatest poem for its use of near, or pararhyme (something Owen probably picked up from his time in France as an English tutor), and for its scenes of cold, dark, lonely hell -- a foreshadow of the entire post-war wasteland (including Eliot's actual The Waste Land (1922)). Owen does something similar to what he does in these two poems, but in prose, in what was to be his "Preface" to his poems. In "Spring Offensive" (also considered by some to be Owen's greatest poem) Owen's traditional Romanticism with Romantic descriptions of nature, experience in 20th Century existentialist hell, and genuine pity for his fellows all come together. Coincidentally, "Spring Offensive" is also probably Owen's last complete poem. (For more on the life and works of Wilfred Owen, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/owen/.)

.jpg) Herbert Read Herbert Read

1893-1968

.jpg) Naked Warriors / by Herbert Read. -- London, Arts & Letters, 1919. Naked Warriors / by Herbert Read. -- London, Arts & Letters, 1919.

"The indefatigably literary" (Fussell, 163) Herbert Read (1893-1968) served as a Captain during the war, winning the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and Military Cross (MC). Read appreciated the close relationship he developed with his men (see "My Company"), and considered making the army a career. However, after the war, Read became a literary and fine art critic. Read was an Imagist poet, and his narrative poem The End of a War is seen by Johnston as leading away from the lyrical form used by Owen, Sassoon, Graves, and others, and towards the epic form employed by David Jones in In Parenthesis (see also Robert Nichols and Ardours and Endurances).

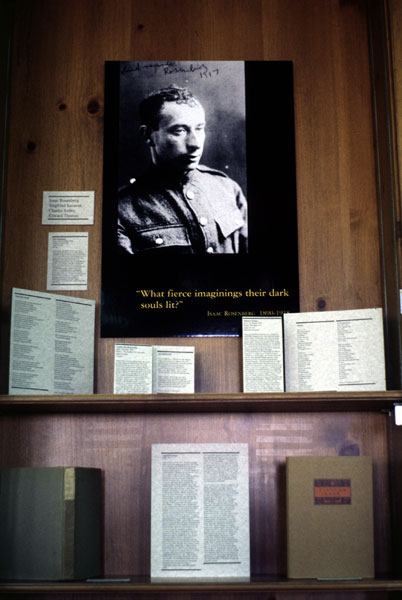

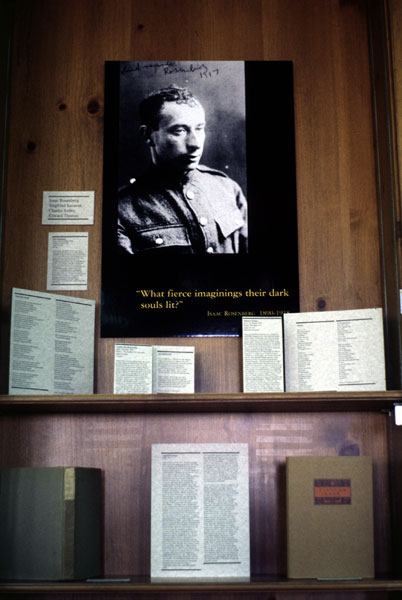

.gif) Isaac Rosenberg Isaac Rosenberg

Born: 25th November 1890

Killed: 1st April 1918

Aged 27 years

Private

.jpg) In the running with Wilfred Owen for the title of greatest of the Great War poets, Isaac Rosenberg is distinguished from the other war poets by the fact that he was both Jewish (as was Siegfried Sassoon) and an enlisted man (as was Ivor Gurney and David Jones). Rosenberg, an artist and Georgian poet, was recuperating in South Africa when war broke out. He enlisted in 1915 (despite weak lungs, general poor health, and being undersize), and served on the Western Front from 1916 until he was killed April 1st 1918. Rosenberg's poem, "Break of Day in The Trenches" is considered by many (see Bergonzi, Fussell, and Stephen The Price of Pity) to be the greatest poem of the war. (Compare John McCrae's "In Flanders Fields," probably the most popular, most anthologized poem of the war.) Another of Rosenberg's best poems is the stark, slightly schizophrenic, and yet thoroughly mezmerizing "Dead Man's Dump." (For more on the life and works of Isaac Rosenberg, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/rose/, and for a specific study of Rosenberg's poem "Break of Day in the Trenches" -- considered the greatest poem of the Great War -- see http://info.ox.ac.uk/oucs/humanities/rose/.) In the running with Wilfred Owen for the title of greatest of the Great War poets, Isaac Rosenberg is distinguished from the other war poets by the fact that he was both Jewish (as was Siegfried Sassoon) and an enlisted man (as was Ivor Gurney and David Jones). Rosenberg, an artist and Georgian poet, was recuperating in South Africa when war broke out. He enlisted in 1915 (despite weak lungs, general poor health, and being undersize), and served on the Western Front from 1916 until he was killed April 1st 1918. Rosenberg's poem, "Break of Day in The Trenches" is considered by many (see Bergonzi, Fussell, and Stephen The Price of Pity) to be the greatest poem of the war. (Compare John McCrae's "In Flanders Fields," probably the most popular, most anthologized poem of the war.) Another of Rosenberg's best poems is the stark, slightly schizophrenic, and yet thoroughly mezmerizing "Dead Man's Dump." (For more on the life and works of Isaac Rosenberg, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/rose/, and for a specific study of Rosenberg's poem "Break of Day in the Trenches" -- considered the greatest poem of the Great War -- see http://info.ox.ac.uk/oucs/humanities/rose/.)

Rosenberg was also a gifted visual artist, and his self-portraits painted before the war, and penciled during, add an additional dimension regarding how Rosenberg perceived himself and the world around him. Martin Stephen has compared Rosenberg to the Romantic poet, artist and visionary, William Blake (The Price of Pity: Poetry, History and Myth in the Great War, 212, 220). Rosenberg was also a gifted visual artist, and his self-portraits painted before the war, and penciled during, add an additional dimension regarding how Rosenberg perceived himself and the world around him. Martin Stephen has compared Rosenberg to the Romantic poet, artist and visionary, William Blake (The Price of Pity: Poetry, History and Myth in the Great War, 212, 220).

.gif) Siegfried Sassoon Siegfried Sassoon

1886-1967

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) spent his privileged, idyllic youth fox-hunting, playing cricket, and writing lyrical, Georgian poetry (which he would then have privately published, at great personal expense, in handsome limited editions). "A country gentleman and literary dilettante" (Giddings 185). He was one of the first to enlist in August 1914, later being commissioned in 1915 into the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Described as "very tall and stately" (Fussell 91), Sassoon was seen by all as "an exceptionally courageous regimental officer" (Giddings 185), "an exceptionally brave officer" (Stephen, Never Such Innocence 346), "an extremely brave and able officer, nicknamed 'Mad Jack' by his men" one of whom remarked "[i]t was only once in a blue moon . . . that we had an officer like Mr. Sassoon" (Fussell 91) -- and he was "elaborately decent" to his men (Fussell 102). For himself though (and especially after the death of a fellow officer, David Thomas, who had been his close friend -- see Sassoon's poem "Enemies"; Robert Graves also was a close friend of David Thomas -- see Graves' poem "Goliath and David"), Sassoon was sometimes foolhardy in taking chances to meet the enemy face-to-face (like Julian Grenfell). On one occasion, he single-handedly captured a German trench, only to then plop down and pull out a book of poetry from his pocket. On April 16th, 1917, Sassoon was wounded in the shoulder and shipped home to recuperate. There, goaded by Bertrand Russell and others, Sassoon's disillusionment over the war (for one thing, his brother Hamo had been killed at Gallipoli in 1915) solidified into his famous protest statement against the continuation of the war, which was eventually read before the House of Commons on July 30th, and published in The Times the next day. Sassoon then politely went A.W.O.L. (declining to report for further duty), threw his M.C. ribbon into the River Mersey, and waited for martyrdom. However the Army hesitated to punish such a public hero as Sassoon (one whose poetry was read and admired by Churchill, among others), and so a way was found, with the help of fellow poet and Royal Welch Fusilier, Robert Graves who came to Sassoon's rescue, of reasoning that Sassoon's reaction was merely shell-shock, and for sending him to Craiglockhart Hospital for a "rest." There he met Wilfred Owen. (See Stephen MacDonald's play Not About Heroes : the Friendship of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen for more about the meeting and friendship of Sassoon and Owen while at Craiglockhart.) both wrote some of their greatest poetry. At Craiglockhart, Sassoon wrote most of the poems that would later make up his Counter-Attack and Other Poems (1918).

.jpg) However, Sassoon knew he couldn't stay at Craiglockhart -- not when his men were still in the trenches. If his protest couldn't help the fighting men, then his place was back with them (his struggle is portrayed poetically in "Sick Leave" and "Banishment"). Sassoon went before a medical board and convinced them that he was quite "cured" and ready to return to the Front. Back in the line, in July of 1918, Sassoon was shot in the head by one of his own sergeants (who thought him a German -- Sassoon joked that it must've been because of his first name) and invalided home. However, Sassoon knew he couldn't stay at Craiglockhart -- not when his men were still in the trenches. If his protest couldn't help the fighting men, then his place was back with them (his struggle is portrayed poetically in "Sick Leave" and "Banishment"). Sassoon went before a medical board and convinced them that he was quite "cured" and ready to return to the Front. Back in the line, in July of 1918, Sassoon was shot in the head by one of his own sergeants (who thought him a German -- Sassoon joked that it must've been because of his first name) and invalided home.

.jpg) Sassoon's poetry is often satirical, leading up to and ending with a "knock-out punch" last line -- as in his poem "The One-Legged Man." However, Sassoon also felt deeply and often the expressed that same understanding of and "pity" for the plight of soldiers that Wilfred Owen is famous for -- Sassoon's poem "Dreamers" is an example. Siegfried Sassoon is a key figure -- perhaps the most important -- in the study of Great War literature. Within a tight-knit group of Great War writers who all seemed to know and influence one another, a group of "insiders," Sassoon is the central figure. It's no wonder that Pat Barker's modern fiction trilogy of the Great War -- Regeneration, The Eye in the Door, and The Ghost Road -- revolves around Siegfried Sassoon. In addition, Sassoon was a survivor, who, while working out his own readjustment, carried the responsibility of remembrance, as he does in his poem "Aftermath" published in Picture Show (1919, 1920). Sassoon's poetry is often satirical, leading up to and ending with a "knock-out punch" last line -- as in his poem "The One-Legged Man." However, Sassoon also felt deeply and often the expressed that same understanding of and "pity" for the plight of soldiers that Wilfred Owen is famous for -- Sassoon's poem "Dreamers" is an example. Siegfried Sassoon is a key figure -- perhaps the most important -- in the study of Great War literature. Within a tight-knit group of Great War writers who all seemed to know and influence one another, a group of "insiders," Sassoon is the central figure. It's no wonder that Pat Barker's modern fiction trilogy of the Great War -- Regeneration, The Eye in the Door, and The Ghost Road -- revolves around Siegfried Sassoon. In addition, Sassoon was a survivor, who, while working out his own readjustment, carried the responsibility of remembrance, as he does in his poem "Aftermath" published in Picture Show (1919, 1920).

Sassoon brought out, to much acclaim, two volumes of poetry during the war: The Old Huntsman (1917), and Counter-Attack (1918). Sassoon's satiric poetry influenced, among others, Wilfred Owen (with whom he was a patient at Craiglockhart Hospital where the two were convalescing). Sassoon was the first to edit a volume of Owen's work. He also championed the literary career of Edmund Blunden. After the war Sassoon wrote of his pre-war, wartime, and post-war experiences in his thinly-fictionalized Memoirs of A Fox-Hunting Man; Memoirs of An Infantry Officer; and Sherston's Progress, a trilogy later collectively titled The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston. Later, Sassoon published three more volumes of autobiography, The Old Century (and Seven More Years); The Weald of Youth; and Siegfried's Journey. (For more on the life and works of Siegfried Sassoon, see the study found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/sassoon/.)

.gif) Charles Hamilton Sorley Charles Hamilton Sorley

Born: 19th May 1895

Killed: 13th October 1915 (at Loos)

Aged 20 years

Captain

Robert Graves said that Charles Sorley was one of the three (along with Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg) truly great poets of the war (in fact, Graves wrote a poem entitled "Sorley's Weather"). Sorley enlisted in 1914, was commissioned in 1915, and as a Captain was killed at the Battle of Loos on October 13th, 1915, at the age of 20. Sorley had been a student in Germany before the war, and presciently surmised the oncoming tragedy in "To Germany." Sorley's sonnet "When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead" is generally interpreted as a rebuttal to Rupert Brooke's sonnet "V. The Soldier." Another well-known Sorley poem, "All the Hills and Vales Along," might also be either a rebuttal to Thomas Hardy's "Men Who March Away," or paean celebrating the fighting man, similar to Julian Grenfell's "Into Battle."

.jpg) Edward Thomas Edward Thomas

Born: 3rd March 1878

Killed: 9th April 1917

Aged 39 years

Second Lieutenant

Before the war, Edward Thomas was a talented but unfulfilled, struggling writer, who supported himself and his family by doing hack work, book reviewing, and by writing travel narratives of his trips to local points interest. Thomas was acquainted with Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, and Rupert Brooke, and was admired by a young musician named Ivor Gurney. In 1914, at Dymock, he became close friends with his American neighbor, Robert Frost, then a frustrated, all-but-unknown poet, who had brought his family to England to "live under thatch." Frost encouraged Thomas to try writing poetry, and Thomas discovered his true voice (although Thomas cautiously at first, publishing his first poems under the pseudonym "Edward Eastaway"). Thomas almost took his family to America with the Frost's when they returned, but feeling the social pressure to enlist, he joined the Artist Rifles in July 1915 at the age of 37. Starting out in the ranks, Thomas was commissioned in 1916, and killed by a shell blast at Arras on April 9th, 1917. Before the war, Thomas wrote a poem entitled "Words." "Years later Ivor Gurney recited this poem at a London literary dinner, saying that it stated all that need be said about the English language" (97). Thomas' reputation as a poet -- and not necessarily as a "war poet" -- has continued to rise, and the environs around Dymock where he lived and wrote, his haunts, have become shrines for pilgrims on literary walking tours. (For more on Thomas' life, see the study of Edward Thomas found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/thomas/, and also see Helen Thomas' 2-volume autobiography, As It Was and World Without End, and for more on Thomas' influence on later poets, see Alun Lewis, and Leslie Norris.) Before the war, Edward Thomas was a talented but unfulfilled, struggling writer, who supported himself and his family by doing hack work, book reviewing, and by writing travel narratives of his trips to local points interest. Thomas was acquainted with Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, and Rupert Brooke, and was admired by a young musician named Ivor Gurney. In 1914, at Dymock, he became close friends with his American neighbor, Robert Frost, then a frustrated, all-but-unknown poet, who had brought his family to England to "live under thatch." Frost encouraged Thomas to try writing poetry, and Thomas discovered his true voice (although Thomas cautiously at first, publishing his first poems under the pseudonym "Edward Eastaway"). Thomas almost took his family to America with the Frost's when they returned, but feeling the social pressure to enlist, he joined the Artist Rifles in July 1915 at the age of 37. Starting out in the ranks, Thomas was commissioned in 1916, and killed by a shell blast at Arras on April 9th, 1917. Before the war, Thomas wrote a poem entitled "Words." "Years later Ivor Gurney recited this poem at a London literary dinner, saying that it stated all that need be said about the English language" (97). Thomas' reputation as a poet -- and not necessarily as a "war poet" -- has continued to rise, and the environs around Dymock where he lived and wrote, his haunts, have become shrines for pilgrims on literary walking tours. (For more on Thomas' life, see the study of Edward Thomas found in the Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature at http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/tutorials/intro/thomas/, and also see Helen Thomas' 2-volume autobiography, As It Was and World Without End, and for more on Thomas' influence on later poets, see Alun Lewis, and Leslie Norris.)

|

.jpg)

.gif)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)